This website had become stale. I should either revive it to some degree–or take it down. So I have decided to update. I don’t expect to be particularly active, but I won’t give it up all together.

I have sent a copy of this on Yale stationary, which you can find attached here (open_letter-to-charles_b_-johnson_9_23_2016).

23 September 2016

Charles B. Johnson

Franklin Resources, Inc.

One Franklin Parkway

San Mateo, CA 94403-1906

Dear Mr. Johnson:

I want to begin––belatedly I know––by thanking you for your incredibly generous gift in endowing one of Yale’s new colleges––Franklin College. I say this as a Yalie: my father was class of ’42, I went to Yale and have now taught here for the last 25 years. My daughter is also a graduate. I have felt for a long time that our university needed to expand the number of students in Yale College, and your gift has done so much to make that possible. Bravo!! I also want to add that your naming the college after Benjamin Franklin has my complete support. Perhaps if I had donated $250 million I would have named it after someone else, but naming it after this remarkable man is certainly a decision I respect—and also understand. So I apologize for some of the statements in the Yale Daily News even as I would like to suggest that the real culprit was the Yale administration rather than the students. The powers-that-be led us to believe that the names of these colleges were open to discussion when, at least in the case of Franklin College, that was not the case. And they tied it to the discussions around Calhoun College, when these two items really are independent. Your Franklin College gift and its announcement should have been handled separately from these other matters. Students (and faculty) felt fooled and were angry. (I went to a number of meetings to contribute my ideas on these matters.) I am so sorry that you have had to endure what might seem a lack of appreciation in some quarters. My own belief is that your generosity is widely appreciated––and will be increasingly so in the years to come.

At the same time I would like to politely disagree with your comments on Calhoun College. As a Yale graduate I was initially not in favor of changing the name of the college. My suggestion was to change whom it was named after—all the Calhouns who graduated from Yale—which includes a student of mine whose father is a black cop in Houston. That received little interest. What I have come to realize is that the issue with Calhoun College is not simply the name. In fact, the college was built around the name John C. Calhoun as a shrine to white supremacy. We were reminded of this when Corey Menafee shattered a stain glass window depicting John C. Calhoun’s slaves in Calhoun dining hall. As you know the kitchen staff is overwhelming African American and it is not surprising that to work under those windows every day became too much to bear. Calhoun College is not a museum: it is a place where people live and work. We need to replace this shrine to white supremacy. It needs to be renamed and reconfigured—not to efface history but to remind Yale students and the world that Yale was more often on the right side of history.

Yes. John C. Calhoun was a Yale graduate but while he was senator for South Carolina, Yale professors were helping the Amistad captives retain their freedom. I think this is very important as we present Yale to the world. And Benjamin Franklin is also very relevant to this issue. According to one source:

In his later years Franklin became vocal as an abolitionist and in 1787 began to serve as President of the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery. The Society was originally formed April 14, 1775, in Philadelphia, as The Society for the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage; it was reorganized in 1784 and again in 1787, and then incorporated by the state of Pennsylvania in 1789. The Society not only advocated the abolition of slavery, but made efforts to integrate freed slaves into American society.

I am totally convinced that Franklin would want us to change the name of Calhoun College. Moreover, there are still other reasons why retaining the name of Calhoun College is untenable. It should concern you that retaining the Calhoun name is going to adversely affect “the Yale brand” as well as its relations with the New Haven community. The Mayor of New Haven has already asked for it to be changed. And there will be recurrent protests that are certain to gain in strength. The administration already worries that students in Calhoun College will at some point sleep out on the Cross Campus rather than in the college. They will be arrested to front page news. (They might do it in the dead of winter so no one will think they are “coddled.”) Students will then insist that they not be assigned to Calhoun College. Yale will have to ask incoming freshmen to tick off a box if they don’t want to be in Calhoun College. Faculty will refuse to be Calhoun Fellows. You can see where this will lead. So I would urge us to channel the spirit of Ben Franklin and do what you have done and (re)name the college after a figure or group we all can admire–and hopefully make the college a monument to Yale’s efforts to end slavery. That is the kind of residence we all should be happy to work, eat and live in.

Sincerely,

signed

Charles Musser

Professor of Film and Media Studies

Professor of American Studies and Theater Studies

For anyone who has dropped in on my website with any frequency, the absence of new posts must be obvious. I hope that will change but I have been grappling with a number of projects with unforgiving deadlines. More about them in future posts. Nevertheless, Orphans X merits at least brief comment. It was a glorious occasion. So let’s begin with a two-shot of the co-hosts:

Nov 24, 2015. I staggered into this Museum of Modern Art for Orphans at MoMA: Animation and Activism, wearier than I might have liked. Too many late nights finishing a manuscript and too many bad sleeps worried if the DMCA would lend cameras to my students in Documentary Film Workshop (they did but only after I went fairly far up the food chain). I brought along my camera and it reveals a lot about my state of being.

sometimes it feels as if I have four friends left in New York––a casualty of teaching out of town all these years So it was nice to see that at least thirteen of them showed up. They came from all sorts of different places:  it was an honest to god reunion. National Treasure Dan Streible was organizing the event, and I guess you could say that friends of Dan are almost by definition mutual friends. Katie Trainer performed the role of Master of Ceremonies (though I should note that the

it was an honest to god reunion. National Treasure Dan Streible was organizing the event, and I guess you could say that friends of Dan are almost by definition mutual friends. Katie Trainer performed the role of Master of Ceremonies (though I should note that the  term Master may soon be outlawed by all those who are politically correct). Actually Dan Streible’s legible picture to the left

term Master may soon be outlawed by all those who are politically correct). Actually Dan Streible’s legible picture to the left  might be compared to my own less successful efforts. Not enough posts. Anyway, Dan showed a little bit of his Fred Ott Sneeze routine and then showed off Fred with a bird (actually an owl).

might be compared to my own less successful efforts. Not enough posts. Anyway, Dan showed a little bit of his Fred Ott Sneeze routine and then showed off Fred with a bird (actually an owl).

I have stopped posting on this website for quite some time. As with so many of my colleagues, the problem is really one of time. I am finishing a book that I hope to get out for the 2016 election. It is entitled Politicking and Emergent Media: US Presidential Elections of the 1890s. (I’ll try to fill in –but no promises.)

Pordenone 2015 was another fabulous festival. I felt somewhat torn between seeing all the films, catching up with friends and colleagues, and writing the coda to the above mentioned book. So very briefly…

There were the customary surprises that make this festival essential, notably some early silent Mexican films (from 1919 onward).

The Library of Congress screened a partially restored version of Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1914), which is much better than the one I show in my Film Historiography class.

It makes even clearer the radical nature of this production –a complete counter to The Birth of a Nation, which followed within the year. (Note: get a copy for the course.)

Some westerns, programmed by Richard Abel, enabled me to understand what Broncho Billy Anderson was all about. He stood out as a star, but even more impressive were the stories–Broncho Billy moves West and becomes the sheriff. His old friend and rival for his wife’s affections shows up. While BB is off chasing a criminal, the man tries to seduce her. Although the man’s attentions are rejected, they are depicted quite extensively, ending in a confrontation. In another one-reeler, BB steals some money to save the life of his best friend. When they both romance the same girl and it seems she prefers BB, the friend reveals the crime and sends BB to prison. When our hero finally gets out he vows revenge but then discovers the woman happy with husband and child. BB relents.

Another unexpected pleasure was seeing the talented stage actor William Gillette in Sherlock Holmes (1916).

I could go on: The Mollycoddle with Douglas Fairbanks has that kind of transformation from naive and incapable to naive and brilliant that Buster Keaton would establish as his trade mark. Hmm.

And Ramona (1928) with Ramona Diaz was an unexpected surprise in which the brutality to Native Americans and Mexican Americans is depicted with surprising (and disturbing) explicitness.

Or the various World War I documentaries, including several Italian documentaries shot in the Alps as the Italians fought the Austrian-Hungarian Empire and On the Firing Line with the Germans (1915) by Wilbur H. Durborough. The latter was particularly interesting for the ways it showed Americans in German during the first two years of the war, including Jane Addams––as a well to emphasize US-German ties.

Such documentaries were shown in the US as pro-German propaganda that became increasingly controversial. Been reading about such documentaries for years–and final saw one!

In terms of immersive experience, the high point of the week was a screening of Paolo Cherchi Usai’s new film Picture (2015) with the Alloy Orchestra. It was an intense, immersive experience inspired by Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera and (one suspects) Enthusiasm.

Silent Cinema is one of my two portfolios at Yale, and it is no secret that I manage to stay up to date with what is happening in this world by spending a week each year at the Pordenone festival. Yet this year had a particular emotional kick. Perhaps it was because the fabulous David Robinson was stepping down as President after 19 years and the younger, equally wonderful Jay Weissberg was taking his place–an elegant transition that is all too rare (bravo Giornate!).

Or that Linda Williams, having retired from UC-Berkeley, was there with her husband.

Or that Jean Darling, the child star of the silent era who was a Pordenone regular, had died.

Or that Jean Darling, the child star of the silent era who was a Pordenone regular, had died.

(The festival was dedicated to her memory.) Or perhaps it was just relaxing with so many good friends (and good wine)–an escape from the ongoing craziness of my university.

So this year I offer a few photos taken with the awareness that we were all so lucky to be there.

I hope to throw in some photos and comments from the last months

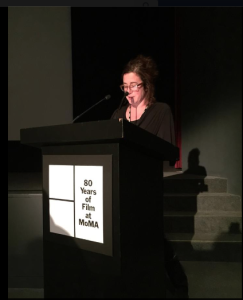

I arranged for Judith Helfand to come to Yale and talk with students in my course on Documentary and the Environment. The week was devoted to her work: my lecture was followed by a showing of Blue Vinyl (2002)–with A Healthy Baby Girl (1997) as an optional extra for dedicated students, of which there were quite a few. She came for the discussion section and later that evening she screened Everything’s Cool (2007) at the School of Forestry and Environmental Studies. It was a great visit–inspiring for students while it gave me a chance to think more about her films and career trajectory.

I arranged for Judith Helfand to come to Yale and talk with students in my course on Documentary and the Environment. The week was devoted to her work: my lecture was followed by a showing of Blue Vinyl (2002)–with A Healthy Baby Girl (1997) as an optional extra for dedicated students, of which there were quite a few. She came for the discussion section and later that evening she screened Everything’s Cool (2007) at the School of Forestry and Environmental Studies. It was a great visit–inspiring for students while it gave me a chance to think more about her films and career trajectory.

Judith is, of course, a prominent member of the New York documentary community; and while we share an NYU connection, our paths failed to overlap for many years. This failure had become sufficiently ridiculous; and so I finally attended a screening of A Healthy Baby Girl at the Stranger Than Fiction series, where Judith did a post-screening Q & A. (The exact date was March 2, 2010.) We met again unexpectedly at the 2014 Big Sky Documentary Film Festival, where we managed to have a drink together at the hotel bar: I was there with Errol Morris: A Lightning Sketch, while she was on a panel of nonprofit funders and TV program commissioners who were overseeing a set of mock pitch sessions for filmmakers looking to fund their next projects. She gave such insightful and supportive feedback that I concluded that my students would benefit from her presence as well.

Judith is, of course, a prominent member of the New York documentary community; and while we share an NYU connection, our paths failed to overlap for many years. This failure had become sufficiently ridiculous; and so I finally attended a screening of A Healthy Baby Girl at the Stranger Than Fiction series, where Judith did a post-screening Q & A. (The exact date was March 2, 2010.) We met again unexpectedly at the 2014 Big Sky Documentary Film Festival, where we managed to have a drink together at the hotel bar: I was there with Errol Morris: A Lightning Sketch, while she was on a panel of nonprofit funders and TV program commissioners who were overseeing a set of mock pitch sessions for filmmakers looking to fund their next projects. She gave such insightful and supportive feedback that I concluded that my students would benefit from her presence as well.

Judith Helfand having lunch with three students from Documentary and the Environment: Samantha Lichtin, Ila Tyagi, and Tasnim Elboute

Judith has consistently focused her powerful documentaries on environmental issues, beginning even with Uprising of ’34 (1995), which she co-directed with George Stoney. As a DES daughter who suffered life transforming cervical cancer, she can speak with special authority on a range of environmental issues, but it is her personal openness, humor and political commitment that utilizes that experiential gravitas to make her remarkable films.

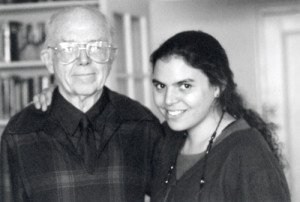

Both Judith and I owe a debt to George Stoney, and I have always been curious why we did not intersect much sooner. Judith took George’s documentary filmmaking class in the spring of 1985, then left NYU to work in the New York world of professional documentary production––just as I was leaving it. After I finished my Ph.D. from NYU in the fall of 1986; George Stoney generously allowed me to teach his two-semester Documentary History course in 1987-88 and 1988-89 while he pursued other projects. It was my first lecture course and the first time I taught documentary. ( I was and will always be grateful to George but truth be told, we did not have much interaction.) In April 1990, faced with a radical hysterectomy at age 25, Judith called George–who offered her a job post-surgery. By the time Judith was working with George, I had left NYU behind and was completing my books on American early cinema. She finally completed her course work and received BFA from NYU in 1994. By then I was program building at Yale. We were ships passing in the night.

Both Judith and I owe a debt to George Stoney, and I have always been curious why we did not intersect much sooner. Judith took George’s documentary filmmaking class in the spring of 1985, then left NYU to work in the New York world of professional documentary production––just as I was leaving it. After I finished my Ph.D. from NYU in the fall of 1986; George Stoney generously allowed me to teach his two-semester Documentary History course in 1987-88 and 1988-89 while he pursued other projects. It was my first lecture course and the first time I taught documentary. ( I was and will always be grateful to George but truth be told, we did not have much interaction.) In April 1990, faced with a radical hysterectomy at age 25, Judith called George–who offered her a job post-surgery. By the time Judith was working with George, I had left NYU behind and was completing my books on American early cinema. She finally completed her course work and received BFA from NYU in 1994. By then I was program building at Yale. We were ships passing in the night.

As I explored Judith’s work, I found myself thinking about documentary partnerships–filmmaking collaborations. I have relied on them myself with mixed success. Much of Errol Morris: A Lightning Sketch depended on a productive collaboration with Carina Tatu, who shot the film and did most of the preliminary editing. Our later efforts were perhaps not so successful, and for various reasons we went separate ways. Currently I am collaborating on a documentary project–Visa Wives––with my wife Threese Serana. And of course there are many collaborative pairs: the Maysles Brothers, Pennebaker-Hegedus, Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky. The list goes on. In any case, Judith has tended to work collaboratively and I was interested in the results. The Uprising of ’34 was George Stoney’s film–his idea and his subject. He initially hired her as an associate producer, but her contributions were such that she became to co-director. She was, one can say, the perfect collaborator in this situation.

While working with George, she was also making A Healthy Baby Girl. For this she had no filmmaking partner though certainly she had supportive associates. There is a scene in the film where she is filming herself sitting on a bed and talking to the camera–strongly reminiscent of Ross McElwee’s Sherman’s March (1986). Our class had already seen several documentaries in which the filmmaker is also the protagonist of the film––Gasland, DamNation, Super Size Me––and of course there are many other documentaries in this period where the filmmaker leads us through the film (e.g. any documentary by Michael Moore and many others by Nick Broomfield). The female filmmaker as protagonist is a rarer phenomenon. Judith and Agnes Varda are the two featured in the course. (I asked Judith about her familiarity with such feminist documentaries of the 1970s as Joyce at 34 [1972] and Nana, Mom and Me [1974]: she had not seen them.) It was on A Healthy Baby Girl, which won a Peabody Award, that Judith hired Daniel Gold as a cameraman. (One thing that was cleared up for me by her visit: her boyfriend Daniel in the film and cinematographer Daniel Gold are two different people.)

Daniel Gold became Judith’s collaborator on her next film: Blue Vinyl, an impressive, wonderful film that my students have been writing about it in their mid-term papers.

There are the the aftermaths of Birth and Death. The baby coming home from the hospital has its counterpart in the funeral. Later there are rituals of a certain symmetry: memorials and baptisms. I confess a certain personal ambivalence about both. One quality they share: the person being baptized or memorialized is either too young or too inert to protest in either instance. Recently I have been going to more memorials than I would like (the third, not discussed here was Paul Robeson, Jr.’s). At the same time, they were ones I would not have missed.

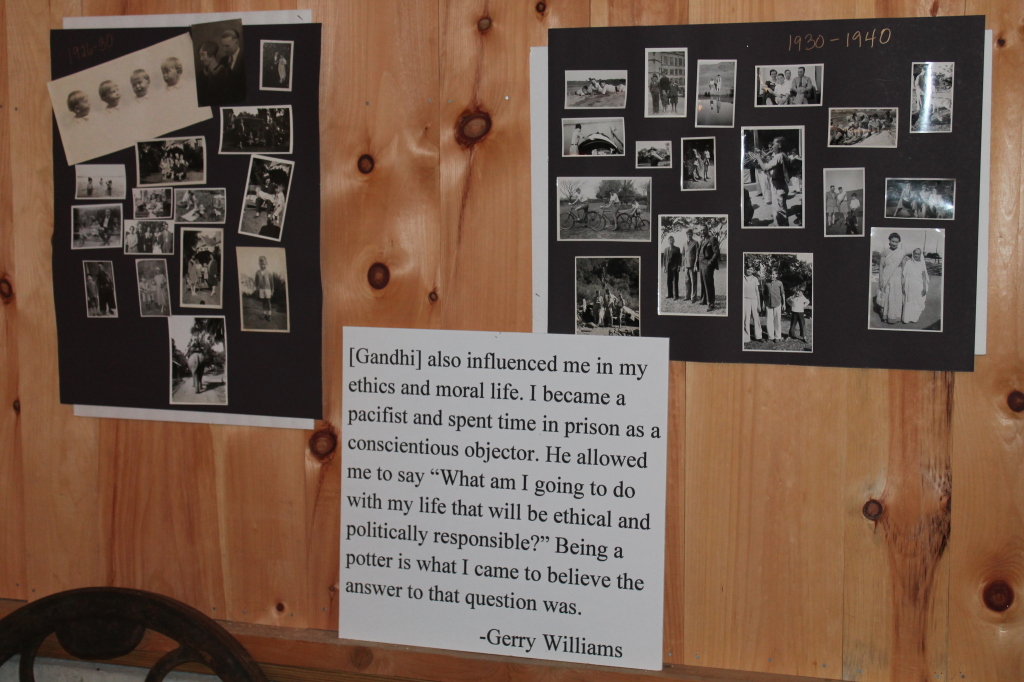

October 18th. I arrived at the Gerry William’s memorial 20 minutes late. There were many reasons hovering in the background. Many parts of the afternoon were certain to be painful. I had also formed a different idea of what was going to happen from the invitation. I imagined people would be eating pot luck food and exchanging stories–as if nothing had changed very much since I first met Gerry at one of his Christmas parties/pottery sales in December 1968. But in death Gerry preeminence partially constrained his style. That idea was not lost (a few of us did bring our pot luck contributions), but it was done more formally than expected. The memorial service was well underway when I arrived. Just as I was sneaking in, the fourth or fifth speaker (Jon Keenan) was explaining to the assembled crowd that “I met Gerry after seeing Charlie Musser’s documentary on Gerry.” Apparently, he was not alone. So it made me ask (again) what did this documentary do? (And what more generally do documentaries do?) How did it change things.

October 18th. I arrived at the Gerry William’s memorial 20 minutes late. There were many reasons hovering in the background. Many parts of the afternoon were certain to be painful. I had also formed a different idea of what was going to happen from the invitation. I imagined people would be eating pot luck food and exchanging stories–as if nothing had changed very much since I first met Gerry at one of his Christmas parties/pottery sales in December 1968. But in death Gerry preeminence partially constrained his style. That idea was not lost (a few of us did bring our pot luck contributions), but it was done more formally than expected. The memorial service was well underway when I arrived. Just as I was sneaking in, the fourth or fifth speaker (Jon Keenan) was explaining to the assembled crowd that “I met Gerry after seeing Charlie Musser’s documentary on Gerry.” Apparently, he was not alone. So it made me ask (again) what did this documentary do? (And what more generally do documentaries do?) How did it change things.

Documentaries can have all sorts of impacts––big and small. The film bound Gerry and me together in its making, and it bound me not just to him but also to his family. He became a surrogate father and perhaps at times I was a surrogate son. Even as I planned the film, it gave me a chance to watch Gerry closely and for long periods of time. As I got ready to make the film, I would just hang out at his studio. Mostly I watched what he was doing (making notes) but we also talked about his philosophical principles and potmaking as a way of being. Not that these were unfamiliar but they became richer and clearer. I would like to think that I absorbed some ethical understandings in the eight years between meeting Gerry and finishing the film, and that these lessons learned have contributed to the way I approach people in my work: how I treat the subjects of my films and essays, how I deal with students, and so forth.

As this memorial confirmed yet again, it helped to create a community out of far flung members. Some people who saw An American Potter went out of their way to see him and some came to the Phoenix Workshops that he ran in the summer.

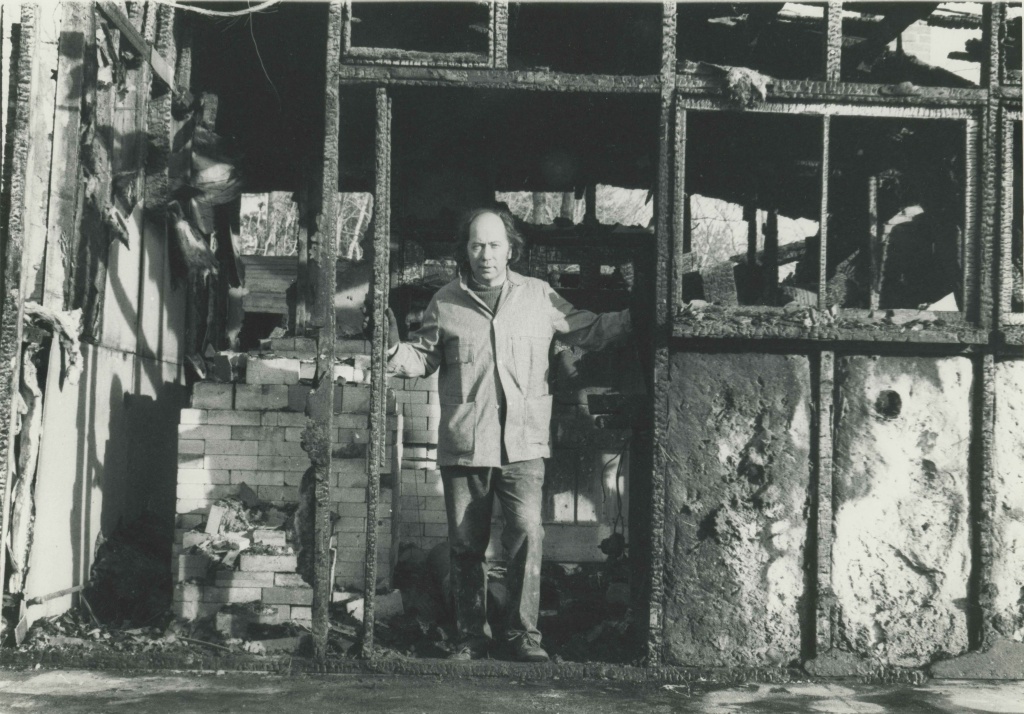

The filming took three weeks to shoot and in those weeks, the understanding was that making the film took priority over making pots. I paid Gerry $300 a week and there was some deferred payment as well but he did a lot of things (the wet firing that opens the film) that cost money for which there was no return. In some respects, I was undoubtedly presumptuous. I was a 26-year-old first-time filmmaker. Truth be told, there was little reason to have confidence about how the film would turn out. Basically he agreed to make the film as an act of generosity.

People were quite pleasantly surprised when they actually saw it. I remember wanting to premiere the documentary in the local Currier Gallery of Art in Manchester. I had met the director David Brooke, probably at an exhibition of Gerry’s pottery. He was quite reluctant–until he saw the film. The film went on to win various awards and it probably helped Gerry’s career in certain modest ways. Certainly it helped to build this community of admirers and friends. And, as I have already said, it became a bond between us. Gerry liked the film and apparently would sometimes take it with him to show people. It was a way to show off his studio and his work. One person, who appeared in the film but was not at the memorial, came to a different conclusion: that the film became a kind of trap for Gerry. The film did not change and what people saw of Gerry was too often what they saw in the film. I don’t think that is entirely true–entirely fair to Gerry or to the film–but I am sure there was an element of truth to that. It is also true that the documentary I recently made of Errol Morris reworks many of the underlying elements of this film. Does that make he a candidate for an auteurist study? Or does it mean I too am somehow stuck?

When Gerry got ill and suffered from a combination of Parkinsons and Alzheimers, the film took on a new significance. Of course there are many ways in which we can remember Gerry–through his pots and other forms of expression (including of course his work as editor of Studio Potter Magazine). His daughter Shelly is beginning to write a biography. But the film, which has Bazinian elements (long takes) has become Bazinian in a different way. It is as AB suggested a kind of death mask. The person who is lost to us is there in front of us, reminding us with considerable force what we have lost. It captured a moment in time when Gerry was at the peak of his creative powers. The disconnect between Gerry in the film and in his increasingly enfeebled state was certainly emotionally fraught. Indeed, just before leaving for the memorial, I spot checked a couple of DVDs that I thought I better bring along in case they were needed. It started the day in an emotional vein. It is still almost impossible for me to watch the film without weeping.

But enough about the film. About the memorial. One thing that happens at memorials is that one sees people one has not seen in a long time or often for the first time. I had been in touch with potter and ceramics professor Jay Lacouture, who teaches at Salve Regina University in Newport, Rhode Island, on email.

He is planning a Williams retrospective at his gallery and was hoping I could come to introduce the film. (It is the same weekend as the Society for Cinema and Media Studies Conference in Montreal and unfortunately this might not be possible.) So we had a chance to finally meet.

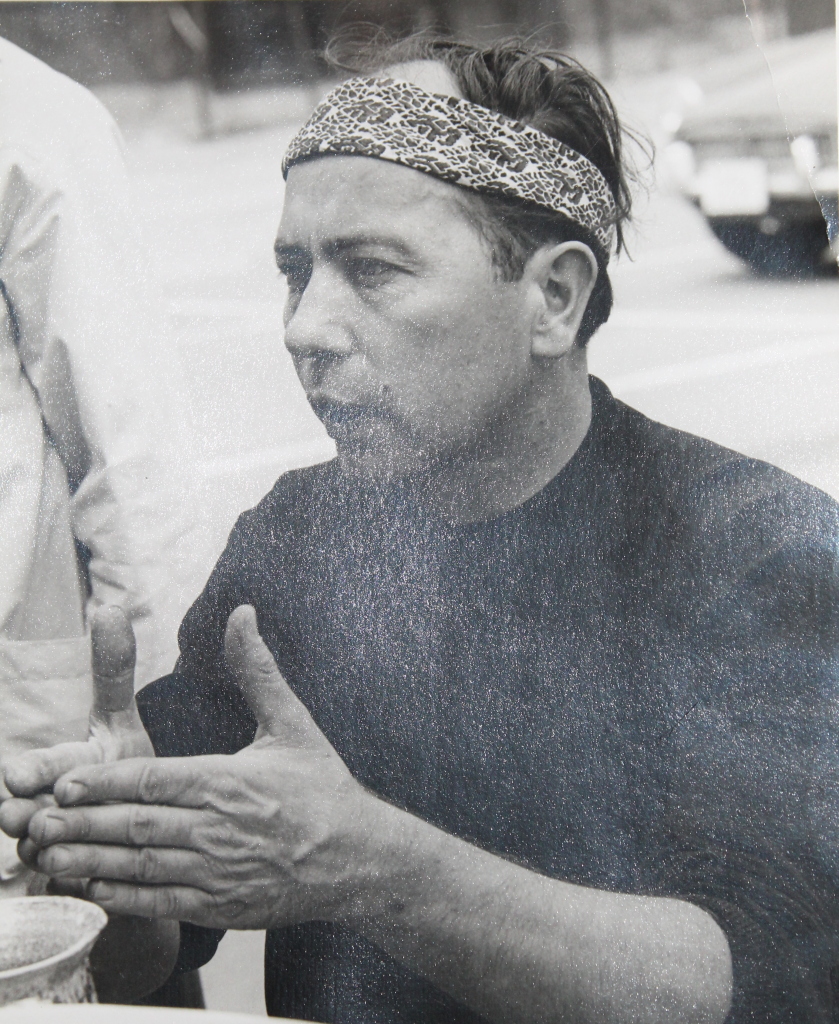

In truth, I was not so up for talking. I spent much of the time looking at the photos of Gerry’s life. I had not seen Bill Finney’s photo of Gerry in a long time. It reminded me that Gerry had some untapped potential as a fashion model. It is interesting and now regrettable that I did not think to have any pictures taken of the two of us. But there was unexpected find on those walls–a picture of me with Julie Williams (surrogate mom).

It is interesting and now regrettable that I did not think to have any pictures taken of the two of us. But there was unexpected find on those walls–a picture of me with Julie Williams (surrogate mom).

As a kind of post-script. Today when I was cleaning up my office I found a box of photographs that had gone missing for awhile. They included photos I had used in An American Potter, of his burned studio and its rebirth through local support (thus the Phoenix Workshops). As Gerry said in the film, the only thing comparable to the destruction of his studio was a death in the family.

***

The following weekend I left behind the history that surrounds my first (non-student) film and turned to my current project, Visa Wives (working title) I am making with my wife Threese.

October 25th: Threese, John Carlos and I went to St. Louis attend the baptism of our nephew (JCs’s cousin) Francis Braulio Serana McGinnis. His mom, Cathy (aka Cheerful) Serana McGinns is Threese’s sister. Part of the excitement was that Father Chester, Cathy’s twin brother, was coming from Cebu to perform the baptism.

They are key figures in our documentary Visa Wives so inevitably, we brought our camera. Making a film about family has some decided benefits. All too often work takes one away from family. In this case, it bring us closer. I did most of the shooting since Threese was often caught up in other responsibilities.These photos were taken by a friend Stephen hired to document the occasion.

They are key figures in our documentary Visa Wives so inevitably, we brought our camera. Making a film about family has some decided benefits. All too often work takes one away from family. In this case, it bring us closer. I did most of the shooting since Threese was often caught up in other responsibilities.These photos were taken by a friend Stephen hired to document the occasion.

Although in some ways it kept me more at the edges, it also kept me much more attentive and engaged. I could imagine attending the baptism and hovering politely in the background. Instead, I was entirely focused on the ceremony, the people attending, even the church itself.

Although in some ways it kept me more at the edges, it also kept me much more attentive and engaged. I could imagine attending the baptism and hovering politely in the background. Instead, I was entirely focused on the ceremony, the people attending, even the church itself.

Although there was some low key suggestions that John Carlos might also participate in the baptismal event, this did not happen for a variety of reasons. First JC’s sister Hannah Grace Zeavin Musser (aka Hannah Zeavin) is a nice Jewish girl. My great grandfather was a Protestant minister though his son (John Musser) stole the clapper from the bell that was donated in his father honor to the prep school he was attending. He married my grandmother but since they were not from the same Protestant denomination, the ministers from either side refused to marry them. There has been a certain degree of distance from any sort of organized religion from that side of the family ever since. And then again, John Carlos’s second mother –Subiya––is a former Hindu who married a Muslim. John Carlos may have gone to mosque more often than to church. Finally when the question was put to John Carlos, he wondered why children needed to baptized since they all come from God. Well… we’ll let him sort that out in the years ahead.

This trip was good in other ways as well. Stephen and I got to compare notes on fatherhood and being married into the Serana family. At the moment Stephen is actually a stay at home dad while Cathy goes to work in the hospital where she is a nurse. He is planning to go back to work in September and they will reorganize their work-life schedule then. It will be interesting to see how reality conforms to their wishes. In any case, Stephen and I connected in a good way, and Threese filmed one of our conversations after Cathy went to work and while Francis (named after Pope Francis) was napping and John Carlos went to get cookies and perhaps a little religious education from his uncle.

***

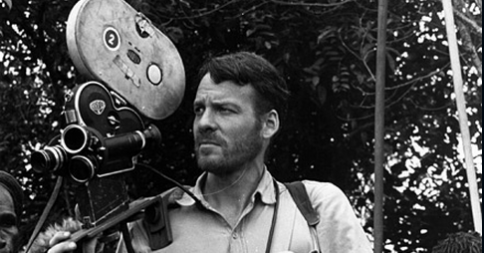

I have had a long, friendly though certainly attenuated relationship with Robert Gardner. It began really when I was taking my first film class with Jay Leyda in the Fall of 1970. It stuck with me. I saw him again when I was being interviewed for a job at Harvard which I did not get (though I was told he had been a supporter). And I brought him to Yale to show a series of his films, including Dead Birds: in fact, the Yale Film Study Center subsequently bought a 35mm print of Dead Birds as a result of that visit. Finally I have been writing a lengthy article entitled “First Encounters: An Essay on Dead Birds and Robert Gardner,” Dead Birds was a film that stayed with me all these years, and I have been intermittently distressed at the ways in which the film has been denigrated, particularly by Jay Ruby and his circle. So given the chance, I finally decided to write about it. I think the essay makes some important points. In the process of the writing, I would correspond with Robert via email. It was a friendly exchange. Mostly I asked for information but I also told him about the rather personal nature of what I was doing. I was planning to email a couple of last questions when Charles Warren informed me that he had died, quite unexpectedly. I was a little stunned. I had a sense that my effort were fostering a more intimate relationship, and everything felt cut short. Not least of all, of course his life. And in this sense his death was quite different than Gerry Williams’ death, which ended a life that had become painfully degraded.

Dead Birds was a film that stayed with me all these years, and I have been intermittently distressed at the ways in which the film has been denigrated, particularly by Jay Ruby and his circle. So given the chance, I finally decided to write about it. I think the essay makes some important points. In the process of the writing, I would correspond with Robert via email. It was a friendly exchange. Mostly I asked for information but I also told him about the rather personal nature of what I was doing. I was planning to email a couple of last questions when Charles Warren informed me that he had died, quite unexpectedly. I was a little stunned. I had a sense that my effort were fostering a more intimate relationship, and everything felt cut short. Not least of all, of course his life. And in this sense his death was quite different than Gerry Williams’ death, which ended a life that had become painfully degraded.

In any case I felt it important to go to Robert’s memorial–to connect with other people who knew him–and also learn some more about his life.

Let me begin this post by expressing my deepest thanks to the organizers of the Pordenone Silent Film Festival–the Giornate del Cinema Muto: David Robinson, Livio Jacob, Piera Patat and Paolo Cherchi Usai among many others. Each year we are blessed to be humble participants in this, your most remarkable, annual achievement. You have legions of fans. I am one.

I am starting to write this post from the Giornate del Cinema Muto in Pordenone, Italy, where I make my annual October pilgrimage for a one week submersion in silent film––one of the two principal areas in my academic portfolio. It keeps me up-to-date in all sorts of important ways. Screenings start at 9 am (sometimes 8:30) and generally run until midnight or soon thereafter. We are here for the films but also to see friends and colleagues from all over the world. Business seems to get done as well–perhaps more about that later. This perfect mix always reminds me (and I think everyone else who’s here) of the reasons why we got into this field. But just to be clear: sitting in a darkened theater for 12 hours a day involves discipline and even training: it is not everyone’s cup of tea. Film festivals invert the relationship between the movie world and the real world. Jet lag makes it even more of a challenge (it is almost impossible to reset your biological clock when in darkness most of the day), but for some reason red wine at meal time helps. It’s a tough job but someone has to do it.

I am starting to write this post from the Giornate del Cinema Muto in Pordenone, Italy, where I make my annual October pilgrimage for a one week submersion in silent film––one of the two principal areas in my academic portfolio. It keeps me up-to-date in all sorts of important ways. Screenings start at 9 am (sometimes 8:30) and generally run until midnight or soon thereafter. We are here for the films but also to see friends and colleagues from all over the world. Business seems to get done as well–perhaps more about that later. This perfect mix always reminds me (and I think everyone else who’s here) of the reasons why we got into this field. But just to be clear: sitting in a darkened theater for 12 hours a day involves discipline and even training: it is not everyone’s cup of tea. Film festivals invert the relationship between the movie world and the real world. Jet lag makes it even more of a challenge (it is almost impossible to reset your biological clock when in darkness most of the day), but for some reason red wine at meal time helps. It’s a tough job but someone has to do it.

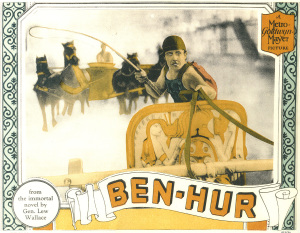

Once again the organizers offered a remarkable program with several strands of material. Speaking personally (a confession?), the festival is often serving a remedial purpose. This quickly became clear on Sunday evening, October 5th, with the screening of Fred Niblo’s Ben Hur (1925). Though the film often indulges in false sentimentality (religious and otherwise), the chariot scene was extraordinary. To be sure, numerous horses (and apparently at least one stuntman) died during the shooting of this scene. The only way to make this picture today would be through digital effects. The spectacle is impressive and it seems that Ramon Novarro, who played Ben Hur, combined remarkable sex appeal with more than decent ability as a film actor. His is another tragic story of a closeted gay star, and this film is poignant testimony to his remarkable talent.

Once again the organizers offered a remarkable program with several strands of material. Speaking personally (a confession?), the festival is often serving a remedial purpose. This quickly became clear on Sunday evening, October 5th, with the screening of Fred Niblo’s Ben Hur (1925). Though the film often indulges in false sentimentality (religious and otherwise), the chariot scene was extraordinary. To be sure, numerous horses (and apparently at least one stuntman) died during the shooting of this scene. The only way to make this picture today would be through digital effects. The spectacle is impressive and it seems that Ramon Novarro, who played Ben Hur, combined remarkable sex appeal with more than decent ability as a film actor. His is another tragic story of a closeted gay star, and this film is poignant testimony to his remarkable talent.

Another long-standing gap is my viewing was filled by the screening of Fritz Lang’s Die Nibelungen (Part 1: Siegfried and Part 2: Kriemhild’s Revenge). Again this shows why the Giornate is so important.

Princess Kriemhild accuses her brother, King Gunther, of killing her husband Siegfried who is also Gunther’s blood brother. She’s right.

Die Nibelungen is not the kind of film that should be seen on a computer or TV screen. It must have suffered many small deaths when shown in old-fashioned projection rooms with a 16mm print. To see this film, one needs an occasion: a free evening, a beautiful 35mm print, a small orchestra, and a full theater.

It is often noted that Lang’s picture was one of Hitler’s favorites. If so, it is hardly surprising that Hitler failed to understand what might be seen as the film’s lesson–its warning. The Germanic Nibelungens wreck havoc on a smaller and darker race, but this violence ultimately produces an orgy of self-destruction in which the

surviving Nibelungens retreat into a bunker and die in a malestrom of fire. This was to be Hitler’s fate as well. Of course, such an interpretation looks at the film in light of future events, rather seeing it as an allegory about the traumas of World War I, as Anton Kaes does in his book Shell Shock Cinema. In fact, Tony and I discussed this very topic over lunch–standing Kracauer’s From Caligari to Hitler: A Psychological History of the German Film on its head. Unfortunately Tony had to leave before the Lang epic was screened, so I missed the post-screening dissection.

surviving Nibelungens retreat into a bunker and die in a malestrom of fire. This was to be Hitler’s fate as well. Of course, such an interpretation looks at the film in light of future events, rather seeing it as an allegory about the traumas of World War I, as Anton Kaes does in his book Shell Shock Cinema. In fact, Tony and I discussed this very topic over lunch–standing Kracauer’s From Caligari to Hitler: A Psychological History of the German Film on its head. Unfortunately Tony had to leave before the Lang epic was screened, so I missed the post-screening dissection.

One major strand of the festival offered films by the Barrymore clan. I am continually fascinated by John Barrymore and his fluid move between theater and film in the 1910s and early 1920s. So it was good to see a nice 35mm print of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1920). Yale has 16mm prints of this and other Barrymore vehicles such as Beau Brummel and The Beloved Rogue (1927), but seeing them in 35mm on a big screen was an entirely new experience, particularly Jekyll and Hyde. Likewise, I had never seen When a Man Loves (1927), a Warner Brothers film with a Vitaphone sound track, made in the immediate wake of Don Juan (1926). One of the things that is so compelling about Barrymore’s film performance is his sense of fun. He doesn’t take any of it too seriously and is always ready to be outrageous. The screwball actor of Howard Hawks 20th Century (1934), in which JB plays Oscar Jaffe, was already present in the 1920s.

In contrast, I knew very little about other Barrymore family members in this period, notably JB’s sister Ethel and brother Lionel. Often guilty of genealogical ignorance, I learned (or perhaps was reminded) that the delightful film comic Sidney Drew was their uncle. To bring this to the present day, it is hard not to notice that Drew Barrymore looks a lot like her great aunt Ethel. The source of her first name is worth noting as well. (Sometimes I am a little slow about these things.)

In The White Raven (1917) Ethel Barrymore plays Nan Baldwin, the daughter of a failed stock broker, who seeks refuge in Alaska gold fields where she sings for a living. Belle of the saloon, she gets offers of marriage but feels trapped. To escape, she sells her self–payment deferred–for funds so she can travel to New York and train as a opera singer. Soon the winner of the competition (William B. Davidson) leaves the gold fields for New York. He meets the newly triumphant Nan, who fails to recognize him without his beard and change of manner. They fall in love, but she refuses his offer of marriage and returns to Alaska and the man who bought her. All turns out happily, of course. As with so many of these Barrymore films, the plots are contrived melodramas and the camerawork is competent but predictable. Other actors are fine but forgettable. What one has is a star vehicle in which Ethel B offers a restrained, effective performance.

In The White Raven (1917) Ethel Barrymore plays Nan Baldwin, the daughter of a failed stock broker, who seeks refuge in Alaska gold fields where she sings for a living. Belle of the saloon, she gets offers of marriage but feels trapped. To escape, she sells her self–payment deferred–for funds so she can travel to New York and train as a opera singer. Soon the winner of the competition (William B. Davidson) leaves the gold fields for New York. He meets the newly triumphant Nan, who fails to recognize him without his beard and change of manner. They fall in love, but she refuses his offer of marriage and returns to Alaska and the man who bought her. All turns out happily, of course. As with so many of these Barrymore films, the plots are contrived melodramas and the camerawork is competent but predictable. Other actors are fine but forgettable. What one has is a star vehicle in which Ethel B offers a restrained, effective performance.

Despite his appearance in some Griffith/Biograph films, my enduring memory of Lionel Barrymore is the wheelchair-bound senior in Key Largo (1948). The Giornate unveiled the early Lionel Barrymore in The Strong Man’s Burden (Biograph, 1913), in which he plays an honorable policeman whose brother (Harry Carey) is a dishonorable thief. Inevitably their paths cross and the policeman (Barrymore) allows his brother to escape, then shoots himself both to cover up his dereliction of duty and to serve as a kind of (self) punishment. The complexity and tension of this melodramatic situation easily allows for a bravura even excessive performance, but Lionel B is so restrained that the character’s psychological agonies are almost effaced.

Restraint but not effacement characterize his powerful performances in The Copperhead (1916) and Jim the Penman (1921). In both films, his character has to operate in highly constrained circumstances in which he must conceal his true feelings. In the earlier film, LB’s character, Milt Shanks, poses as a Southern sympathizer during the Civil War (at the personal behest of Abraham Lincoln, no less), using that position to pass on information that the Union army can use against the Confederates. His wife and son are angered and dismayed by his apparent choices. Inevitably his outward persona and inward feelings are at war with each other; and in fact they are forced to remain this way long after the war ends. Finally he is shot by a Southern sympathizer he seemingly befriended but actually betrayed. Only as he lays dying is this ardent Unionist able to drop his tortuous mask, making death its own kind of release.

In Jim the Penman, James Ralston (Lionel B) loves the daughter of his employer, a banker whose get rich schemes puts him on the edge of bankruptcy. Against his better judgment, Ralston forges a check and is quickly entrapped by a criminal organization for which he must work, against his will (though also with mixed emotions as he prospers personally). Again this tension between calm public persona and internal psychic torture facilitates a retrained but intense acting style, which finally explodes in the final reel as Ralston sends the criminal gang–and himself–to the bottom of the sea, trapped inside a sinking boat.

The Bells (1926), directed by James Young, is set in Eastern Europe during the 19th century. The film serves as another vehicle for Lionel Barrymore who gives a tour de force performance as Mathias, a tavern owner and small time businessman who is too easy going and too generous with his money. Even as his finances spin out of control, he strives to become the local mayor by dispensing drinks and other gifts he can ill afford. Opportunistically, he solves his financial problems by murdering a Jewish pedlar, taking his money belt of gold, and then disposing of his body in a lime kiln. Although he may enjoy the respect of his fellow townspeople and his daughter finds happiness in a desirable marriage, Mathias is tortured by guilt and the threat of discovery. The pedlar’s brother arrives and seeks the murderer, offering a large reward. A clairvoyant (Boris Karloff) hovers, ready to read his mind. Mathias unravels over the course of the film as his hallucinations and dreams become more and more overwhelming. It reminds me of Charles Gilpin’s performance in Ten Nights in a Barroom (Colored Players of Philadelphia, 1926)–the same year.

The most outrageous member of the Barrymore clan was Sidney Drew. His short Goodness Gracious: Or the Movies as They Shouldn’t Be (1913) with Clara Kimball Young has been available through the Museum of Modern Art Circulating Collection for years—but always in 16mm. One can never see this film too many times and it was a treat to see it in 35mm. So much for narrative logic.

The most outrageous member of the Barrymore clan was Sidney Drew. His short Goodness Gracious: Or the Movies as They Shouldn’t Be (1913) with Clara Kimball Young has been available through the Museum of Modern Art Circulating Collection for years—but always in 16mm. One can never see this film too many times and it was a treat to see it in 35mm. So much for narrative logic.

At the very beginning of the Giornate, they screened a number of comedies featuring Mr. and Mrs. Sidney Drew. Most were from the Library of Congress, which is a good thing since I arrived part way through the screening in a jet lag daze.  Her Anniversaries (1917) was pretty hilarious as the wife has a long list of anniversaries, which her husband fails to remember to her great pain and his sorrowful regret. Having once been married to a woman whose calendar was filled with anniversaries of a somewhat different kind–usually involving deaths––I could not fail to identify with the husband’s impossible task–since I too tend to be oblivious. The Drews were a lovely team with perfect comic timing. This is where Sidney D was like John B: both seem to be having a tremendous amount of fun doing what they were doing in front of the camera. Beyond these random observations, both Clara Kimball Young and Mrs. Sidney Drew (Lucile McVey) should be kept in mind for my imagined book A Feminist Moment in the Arts, 1910-1913.

Her Anniversaries (1917) was pretty hilarious as the wife has a long list of anniversaries, which her husband fails to remember to her great pain and his sorrowful regret. Having once been married to a woman whose calendar was filled with anniversaries of a somewhat different kind–usually involving deaths––I could not fail to identify with the husband’s impossible task–since I too tend to be oblivious. The Drews were a lovely team with perfect comic timing. This is where Sidney D was like John B: both seem to be having a tremendous amount of fun doing what they were doing in front of the camera. Beyond these random observations, both Clara Kimball Young and Mrs. Sidney Drew (Lucile McVey) should be kept in mind for my imagined book A Feminist Moment in the Arts, 1910-1913.

The Giornate also allowed us to compare three 1920s leading male stars of the swashbuckling, adventure-historical romance genre: Navarro, John Barrymore and Douglas Fairbanks.

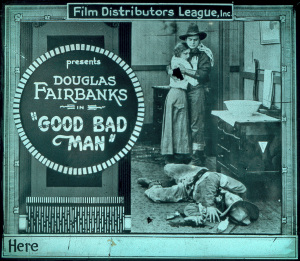

We were able to see Fairbanks in action in one of his earlier films: the comic western The Good Bad Man (1915, a re-released version from 1923), directed by Allan Dwan, written by Fairbanks and shot by Victor Fleming. “Passin’ Through” (Fairbanks) conducts a slew of hold-ups for the sheer joy of it: holding up a train, he takes the conductor’s ticket punch, etc. The film turns serious when romance enters as “Passin’ Through” (Fairbanks) meets Amy (Bessie Love). Meanwhile the bandit king––Bud Frazier/the Wolf (Sam De Grasse)–wants Amy for himself and then it turns out that Bud Frazier had also killed the father of “Passin’ Through” when he was young–creating a parallel between the character and Fairbanks, whose father disappeared when he was five. The melodrama ends in the usual fashion. Not without charm (as William K. Everson might say), the film offers elements that would be reworked more memorably in slightly later films such as Wild and Woolly (1916). It also invites comparison with John Barrymore in The Incorrigible Dukane (1915), another film set in the west in which the ne’er-do-well son (JB) saves his father professional reputation and the dam he is building.

We were able to see Fairbanks in action in one of his earlier films: the comic western The Good Bad Man (1915, a re-released version from 1923), directed by Allan Dwan, written by Fairbanks and shot by Victor Fleming. “Passin’ Through” (Fairbanks) conducts a slew of hold-ups for the sheer joy of it: holding up a train, he takes the conductor’s ticket punch, etc. The film turns serious when romance enters as “Passin’ Through” (Fairbanks) meets Amy (Bessie Love). Meanwhile the bandit king––Bud Frazier/the Wolf (Sam De Grasse)–wants Amy for himself and then it turns out that Bud Frazier had also killed the father of “Passin’ Through” when he was young–creating a parallel between the character and Fairbanks, whose father disappeared when he was five. The melodrama ends in the usual fashion. Not without charm (as William K. Everson might say), the film offers elements that would be reworked more memorably in slightly later films such as Wild and Woolly (1916). It also invites comparison with John Barrymore in The Incorrigible Dukane (1915), another film set in the west in which the ne’er-do-well son (JB) saves his father professional reputation and the dam he is building.

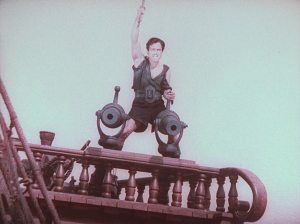

It is the Fairbanks of The Black Pirate (1926) that surprised me the most. The film was shown in lovely two-strip technicolor (the reason for its screening as part of a technicolor strand to the festival), but as I walked out of the theater I found its underlying ideology completely reactionary. Fairbanks is a duke who becomes a pirate king only to outwit –and out fight–the evil band of lowly plebeians. He does so in large part to rescue the helpless princess (Billie Dove), whom he is posed to marry at film’s end. Is there any way, to rescue this film’s horribly class-ist assumptions? Perhaps. We might consider Dove to be a Pickford stand-in at a time when Fairbanks and Pickford were cast in the role of Hollywood royalty. Color can be seen to reduce this film to a fantasy world that references nothing more than Hollywood itself. Certainly Fairbanks does his acrobatics and plays his role with swashbuckling gusto. As an aside, the high point of this Fairbanks films is when a boat-load of men dressed in leather (looking like frequenters of some gay bar of the 1980s) row a galley to the rescue (reminding us of Ben Hur). I was not unhappy to find myself immersed in the swashbuckling genre of the mid 1920s. Sophisticated, self-knowing and perhaps nodding to World War I but from an US perspective in which Americans could think of themselves as saviors (what do you think Tony Kaes?). But the economic inequalities it celebrates (Ben Hur is a prince, while JB plays a chevalier in When a Man Loves) anticipate the Depression and breadlines of the 1930s when examined from a Kracauerian POV). In any case one might compare The Black Pirate to a film in the genre from the next decade–Errol Flynn in Captain Blood (1937). And Pirates of the Caribbean with Johnny Depp evokes the Fairbanks vehicle in ways that are disquieting.

It is the Fairbanks of The Black Pirate (1926) that surprised me the most. The film was shown in lovely two-strip technicolor (the reason for its screening as part of a technicolor strand to the festival), but as I walked out of the theater I found its underlying ideology completely reactionary. Fairbanks is a duke who becomes a pirate king only to outwit –and out fight–the evil band of lowly plebeians. He does so in large part to rescue the helpless princess (Billie Dove), whom he is posed to marry at film’s end. Is there any way, to rescue this film’s horribly class-ist assumptions? Perhaps. We might consider Dove to be a Pickford stand-in at a time when Fairbanks and Pickford were cast in the role of Hollywood royalty. Color can be seen to reduce this film to a fantasy world that references nothing more than Hollywood itself. Certainly Fairbanks does his acrobatics and plays his role with swashbuckling gusto. As an aside, the high point of this Fairbanks films is when a boat-load of men dressed in leather (looking like frequenters of some gay bar of the 1980s) row a galley to the rescue (reminding us of Ben Hur). I was not unhappy to find myself immersed in the swashbuckling genre of the mid 1920s. Sophisticated, self-knowing and perhaps nodding to World War I but from an US perspective in which Americans could think of themselves as saviors (what do you think Tony Kaes?). But the economic inequalities it celebrates (Ben Hur is a prince, while JB plays a chevalier in When a Man Loves) anticipate the Depression and breadlines of the 1930s when examined from a Kracauerian POV). In any case one might compare The Black Pirate to a film in the genre from the next decade–Errol Flynn in Captain Blood (1937). And Pirates of the Caribbean with Johnny Depp evokes the Fairbanks vehicle in ways that are disquieting.

The festival is not just about films. A number of new books were having their festival debut. Laura Horak, a former Yale Film Studies major who subsequently received her Ph.D. at UC-Berkeley and is now teaching at Carleton University, had a book that was distributed to festival donors: Silent Cinema and the Politics of Space (edited by Jennifer M. Bean, Anupama Kapse, and Laura Horak). Laura was at the Giornate with her husband Gunnar Iversen. Knowing my devotion to the beginnings of cinema and my article on The John C. Rice-May Irwn Kiss, they spontaneously staged a re-enactment for my camera during a brief break between films:

The festival is not just about films. A number of new books were having their festival debut. Laura Horak, a former Yale Film Studies major who subsequently received her Ph.D. at UC-Berkeley and is now teaching at Carleton University, had a book that was distributed to festival donors: Silent Cinema and the Politics of Space (edited by Jennifer M. Bean, Anupama Kapse, and Laura Horak). Laura was at the Giornate with her husband Gunnar Iversen. Knowing my devotion to the beginnings of cinema and my article on The John C. Rice-May Irwn Kiss, they spontaneously staged a re-enactment for my camera during a brief break between films:

This confirms something we know well: scholars of early cinema have a strong appreciation for inter-textuality as well as a wonderful sense of humor!

John Fullerton, who teaches at Stockholm University and is responsible for my first visit to Sweden, was at the festival with his wife Elaine.

John and Elaine are festival regulars, but this year they had something special to celebrate: the publication of his book: Picturing Mexico: From the Camera Lucida to Film. Over lunch, I got John to inscribe my copy.

Picturing Mexico is published by John Libbey, one of early cinema’s secret weapons when it comes to publications (his imprint is distributed in the US by Indiana University Press). I wrote the introduction to another recent John Libbey publication, Before the Movies: American Magic Lantern Entertainment and the Nation’s First Great Screen Artist, Joseph Boggs Beale by Terry Borton and Deborah Borton. John Libbey held a Pordenone book party, which the Bortons did not attend. Nevertheless, all three authors of American Cinematographers in the Great War, 1914-1918 were there: James W. Castellan, Ron van Dopperen, and Cooper C. Graham.

Picturing Mexico is published by John Libbey, one of early cinema’s secret weapons when it comes to publications (his imprint is distributed in the US by Indiana University Press). I wrote the introduction to another recent John Libbey publication, Before the Movies: American Magic Lantern Entertainment and the Nation’s First Great Screen Artist, Joseph Boggs Beale by Terry Borton and Deborah Borton. John Libbey held a Pordenone book party, which the Bortons did not attend. Nevertheless, all three authors of American Cinematographers in the Great War, 1914-1918 were there: James W. Castellan, Ron van Dopperen, and Cooper C. Graham.

John Libbey received numerous thanks. I happily toasted him with his own wine while Professor Vanessa Toulmin provided John with a properly chaste imitation of May Irwin’s osculation–one completely in keeping with her new role as Head of Engagement at University of Sheffield.

The Giornate is not all celebrations and kisses. It is no secret that business gets done at this event. Archivists attend the festival so they can hold highly confidential meetings to determine the fate of silent cinema and future restorations. Bryony Dixon of the BFI and Mike Mashon of the Library of Congress met momentarily on the street, no doubt setting up just such a power coffee.

The Giornate is not all celebrations and kisses. It is no secret that business gets done at this event. Archivists attend the festival so they can hold highly confidential meetings to determine the fate of silent cinema and future restorations. Bryony Dixon of the BFI and Mike Mashon of the Library of Congress met momentarily on the street, no doubt setting up just such a power coffee.

Later that day independent film scholar Stephen Bottomore and David Francis met to talk about the imminent opening the new Kent Museum of the Moving Image, which David has created with his wife “Professor” Joss Marsh.

What about my own projects you might ask. Well, two of my current projects definitely received a boost.

I had a power lunch with Mike Mashon, and before I could bring it up, he was talking about the various films made by Carl Marzani and Union Films in the LOC collection. He was eager to get them out into the world and wondered if I was still interested in Union Films. Still interested! My suggestion of lunch had ulterior motives; and even as he raised this question, I had been trying to figure a way to discretely introduce Union Films into our conversation. The Union Films Project (core members: Dan Streible and the Orphan Film Symposium, Walter Forsberg and the Smithsonian, along with myself and the Yale Film Archive) has just added a new member. Yes!

I had a power lunch with Mike Mashon, and before I could bring it up, he was talking about the various films made by Carl Marzani and Union Films in the LOC collection. He was eager to get them out into the world and wondered if I was still interested in Union Films. Still interested! My suggestion of lunch had ulterior motives; and even as he raised this question, I had been trying to figure a way to discretely introduce Union Films into our conversation. The Union Films Project (core members: Dan Streible and the Orphan Film Symposium, Walter Forsberg and the Smithsonian, along with myself and the Yale Film Archive) has just added a new member. Yes!

The boost to a second project was much more unexpected. The Giornate was showing Toll of the Sea (1922) in its two-strip Technicolor strand. The picture’s place in film history is assured as the first technicolor feature. I had seen it more than once, though not, as it turned out, since I met my wife Threese Serana who is from the Philippines. I thought I would watch the first few minutes before heading out to grab a coffee. Instead I stayed, riveted by this movie that speaks so directly to the many stereotypes that we have encountered––from family as well as strangers. It is these stereotypes that compelled us to start work on our documentary with the working title Visa Wives, about the many women from the Philippines who come to the United States on K-1 or fiancée visas.

Toll of the Sea will somehow find its way into our film. Moreover, it was interesting to see that Technicolor was used for two other films of Asia exotica: The Love Charm (1928) and Manchu Love (1929). In The Love Charm, the captain of a yacht that is sailing the South Seas, glimpses a group of Polynesian women through his telescope and is immediately smitten. Upon reaching the island, he falls for a particularly alluring dancer, who fortunately turns out to be the daughter of a Western trader, who had gone native. Her white blood, of course, solves all the awkward problems of interracial romance. He can apparently have his cake and eat it, too. She can, likewise, fulfill all rescue fantasies.

In The Love Charm, the captain of a yacht that is sailing the South Seas, glimpses a group of Polynesian women through his telescope and is immediately smitten. Upon reaching the island, he falls for a particularly alluring dancer, who fortunately turns out to be the daughter of a Western trader, who had gone native. Her white blood, of course, solves all the awkward problems of interracial romance. He can apparently have his cake and eat it, too. She can, likewise, fulfill all rescue fantasies.

Another essential aspect of Pordenone screenings involves refining and perhaps correcting my earlier projects. In this regard the program of short films by Paul Nadar, made between 1896 and 1898, was particularly noteworthy–-and it matched one shown last year of films made for the Cinématographe Joly, which utilized a 35mm format but with five perforations, offering a more vertical image. It was its own distinct system–similar to, but incompatible with, the Edison and Lumiere projects. Nadar also had his own patented motion picture system, one which did not use sprocket film. It did not work very well so he also developed an Edison-compatible system. Nevertheless, this underscores the fact that there were numerous efforts to develop what we would now call non-standard systems. The Edison system marginalized most of these efforts–including Nadar’s––quite quickly. In this regard, Edison’s sale of kinetoscope films on an international basis and the appropriation of that format and technology by R.W. Paul, Birt Acres and others proved to be crucial.

Nadar’s films were of excellent quality. He took some street scenes but he also made dance films, including ones that featured Serpentine and Butterfly dancers. There is an early Serpentine film that is often attributed to Edison, but does not look as if it was shot in the Black Maria. I wonder if it is not Nadar’s. I have to find the still which is somewhere in my collection. What it would suggest–no surprise–is that Nadar’s films reached the US where they found a market.

Then there are moments like this one. Ana Grgic, a Ph.D. student at St. Andrews, had emailed me about a newspaper article that discusses Edison’s Blacksmith Scene (1893). Except the article, which is in Croatian, dates from November 1892. (It is likely a translation from an early article, possibly in German.)

Rather than correspond, I asked if Ana was coming to the Giornate. She was and so we met for a power coffee. What to make of this? Good question, but if the article is really about a blacksmith scene at the Edison Laboratory, our history of this period is going to need some refinement. At the very least it means the Blacksmith Scene was not shot in the Black Maria. Somewhat bewildered, I introduced Ana to Paul Spehr, whose book The Man Who Made Movies: W.K.L. Dickson (2008) is the latest word on this subject. In my excitement, I did not realize that Paul was about to go on stage and accept the Prix Jean Mitry for his outstanding life-long contribution to the study of early cinema.

One last example in this vein: the German Tonbilder films (sound films) made between 1907 and 1909. These films, including arias from Rigoletto and the opera Martha, were remarkable. They were one-shot films of three to four minutes, using techniques that have become standard for popular film musicals –lip syncing to pre-recorded music. The same kinds of films were also quite popular in the US at this time (the Cameraphone). The camera is always static and the films lack narrative. By the 10th film, my initial pleasure began to fade and that is what must have happened in Germany and the US by the later part of 1909. For more on these films see a blog by Antti Alanen.

One last example in this vein: the German Tonbilder films (sound films) made between 1907 and 1909. These films, including arias from Rigoletto and the opera Martha, were remarkable. They were one-shot films of three to four minutes, using techniques that have become standard for popular film musicals –lip syncing to pre-recorded music. The same kinds of films were also quite popular in the US at this time (the Cameraphone). The camera is always static and the films lack narrative. By the 10th film, my initial pleasure began to fade and that is what must have happened in Germany and the US by the later part of 1909. For more on these films see a blog by Antti Alanen.

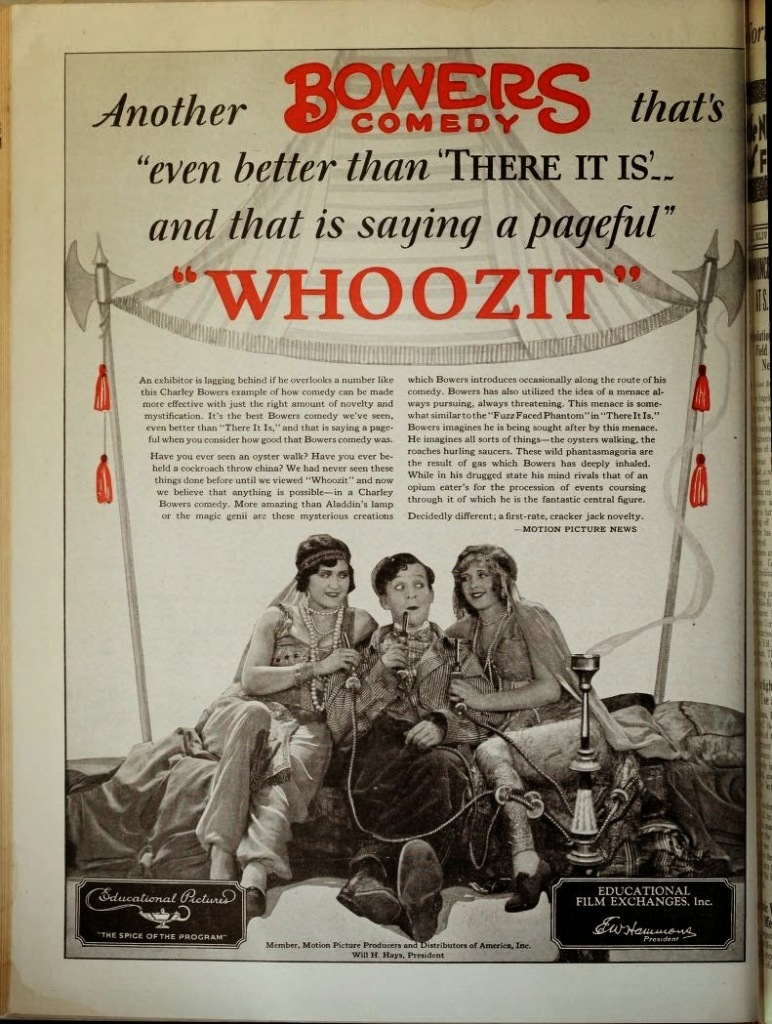

One debate that may never end continues to revolve around the relationship between “cinema of attractions” and narrative film. Just to say that there were plenty of reminders that non-narrative attractions continued to appear in movie theaters with noteworthy regularity. These included such color shorts as Coloring the Stars: Number Four (1926) which showed a number of stars lounging at home, and Colorful Fashions from Paris (1926), a fashion show on film sponsored by McCall’s Magazine. Then there were the films that defied any narrative logic. They were not simply non-narrative (like the previous two), they were anti-narrative, specifically undoing, upending and refusing conventional Hollywood narratives. These include the previously mentioned Goodness Gracious (1913) with Sidney Drew and the Charlie Bower comedy Whoozit (1928). The following image is stolen from Antti Alanen blog. My thanks and apologies to him:

Of course there were more films, many more meals, and many late-night drinks that are not mentioned here. It is impossible to fully encompass the Giornate experience.

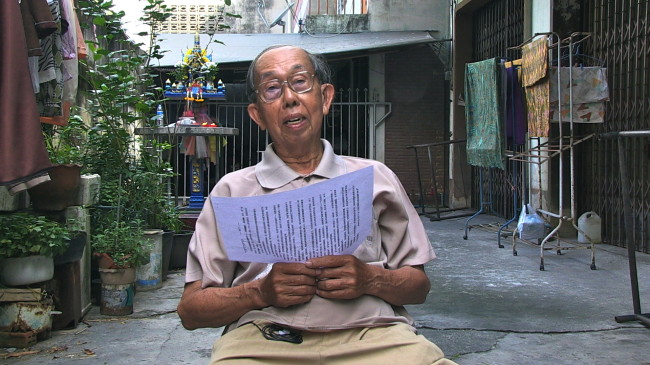

So here are some miscellaneous notes/highlights. Benshi Ichiro Kataoka came from Japan to accompany a group of Chaplin films, including Kid Auto Races at Venice (1914). Ichiro also gave a compelling lecture on the Benshi, translated from Japanese to English. Impressive.

So here are some miscellaneous notes/highlights. Benshi Ichiro Kataoka came from Japan to accompany a group of Chaplin films, including Kid Auto Races at Venice (1914). Ichiro also gave a compelling lecture on the Benshi, translated from Japanese to English. Impressive.

The Italian Association for Research on Cinema History celebrated its 50th anniversary. Founded in 1964, the only survivor from that occasion, Aldo Bernardini, took the stage to mark this occasion.

Meals with Andre Gaudreault, Vanessa Toulmin, Ian Christie, Chris Horak, Pat Loughney, Hiroshi Komatsu, Susan Ohmer and Don Crafton, Linda Williams, Diane and Richard Koszarski, Dana Benelli, Ansje van Beusekom, Paul Spehr, David Mayer, Karen and Russell Merritt.

On the left: Giornate fans who come with their own home-made T-shirts. If they contact me, I have a few more stills to give them. On the right, Market Day.

until next year…

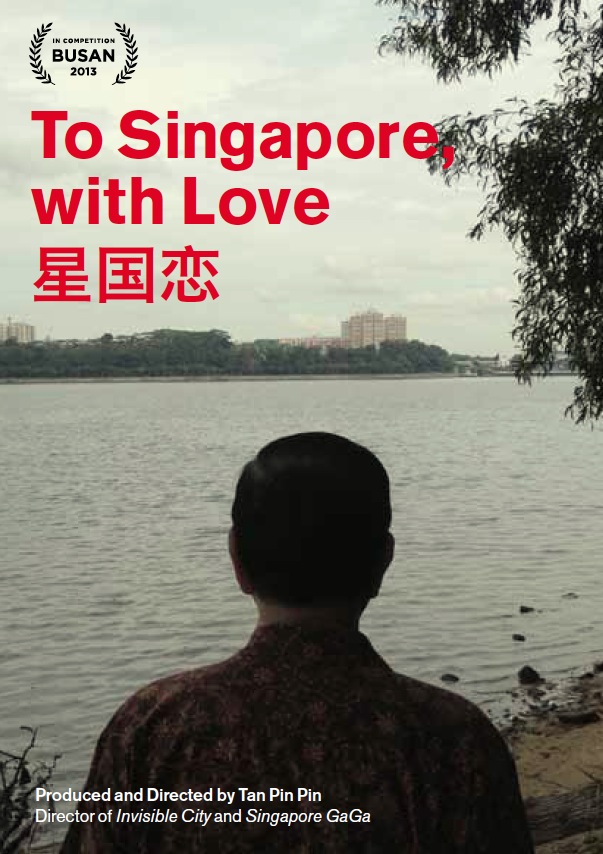

I’ve been reading about the city state of Singapore banning Tan Pin Pin’s To Singapore with Love, first in the Yale Daily News and then elsewhere.

My friend Jim Sleeper, who is a Yale lecturer in Political Science, followed up with an opinion piece in the Yale Daily News and then another in the Huffington Post. Meanwhile, I dashed off a letter to the YDN, which has produced silence after an initial acknowledgment. I thought I’d publish it here!

My friend Jim Sleeper, who is a Yale lecturer in Political Science, followed up with an opinion piece in the Yale Daily News and then another in the Huffington Post. Meanwhile, I dashed off a letter to the YDN, which has produced silence after an initial acknowledgment. I thought I’d publish it here!

The upshot of all this was productive or at least interesting––for me. I got in touch with Tan Pin Pin through Facebook (both Tan and To Singapore with Love have Facebook pages).

Tan is a graduate of Northwestern where my early cinema colleague Scott Curtis inflicted one or more of my articles on her so I wasn’t a totally unknown quantity. For the moment at least, she is definitely not interested in showing her documentary at either Yale-New Haven or Yale-NUS. This is totally understandable, of course. The film has its own roll-out on the festival circuit and showing the film here could further complicate an already difficult situation.One thing that has surprised me. Apparently Yale graduate students don’t read the YDN and so all of the Film and Media Studies Ph.D. knew nothing about it. Even more surprisingly few knew about it in my documentary film workshop. But then a lot is going on in the world right now–Hong Kong, Ukraine, Middle East, Ebola, and so forth.

I also got in touch with my counterpart at Yale-NUS. He is a little shell-shocked from the university’s handling of the situation (the proposed screening of To Singapore with Love), so I will leave his name out of this post for the time being, but it was nice to discover some interesting connections.

And now the New York Times is doing an article on Tan’s documentary, “Banned Film Reunites Singapore with its Exiles.”