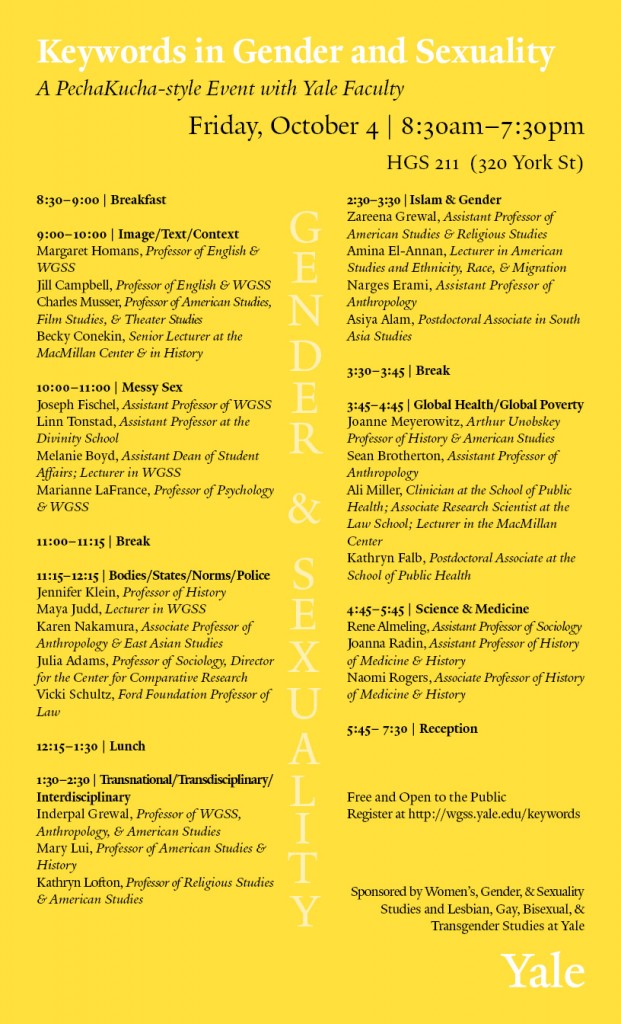

At the Keywords Conference at Yale on October 4, 2013, I gave a précis of a book project–one of my many. Perhaps one should be discrete about these things, but I have already published two of the chapters in article form. So the cat is at least partially out of the bag.

The requirement for the conference was something like 7 minutes with 20 slides, known as Pechakucha –style. Normally I fight these kinds of dictates but I found it an interesting challenge. So here are my bullet points:

- A Feminist Moment in the Arts: 1910-1913 is the title of a book I am working on. I have published the core of two chapters and have imagined the other three. So I am giving a lightning sketch of the project today. As you might expect, it owes a lot to Nancy Cott and her book The Grounding of Modern Feminism. It will probably be dedicated to my daughter Hannah Zeavin who was the editor in chief of Broad Recognition: A Feminist Journal at Yale and, ignoring my plea that one troublemaker in the family was enough for this university, was one of the signators of the Title IX Complaint a few years ago. In fact, she proved to be the poster child of that particular action.

- Not surprisingly the key word for this talk is “feminism.” As Nancy Cott remarked, the term entered the mainstream ca. 1913. I have traced its appearance in the New York Times and the New York Tribune: As you can see from this chart over the course of 1910, the term “feminism” appeared in 4 different items in the New York Times and 3 items in the New York Tribune . During 1911, 20 and 2 different items respectively and for 1912—16 and 4 items. But the term appeared in 61 different items in the Times and 26 different Tribune items over the course of 1913, in 86 (Times) and 101 (Tribune) different items in 1914, 74 and 98 in 1915, then 40 and 34 in 1916, 24 and 27 in 1917, and 22 and 13 in 1918.

- And here is that famous quote by Virginia Wolfe about the world changing around 1910. Not all at once because it would seem there was a turning point around 1913. So I am interested in the process of cultural and social change around issues of gender with two parallel phenomena during my life time—2nd wave feminism in the late 1960s and gay rights, which in recent years has focused on gay marriage. This is one reason why the book may be of some broader interest.

- So here is the break down of the book:

- Chapter 1: Sarah Bernhardt. A number of important things happened to the Divine Sarah in 1910. In October Bernhardt embarked on her American theatrical tour with a new leading man: Lou Tellegen. Thirty-seven years her junior, he quickly became her highly appreciative lover. While the ship’s passengers celebrated her birthday in route, she remained in her cabin the entire time while Tellegen supposedly read her Shakespeare.

- She arrived in New York ready to perform a new version of Joan of Arc. She was met by 100 members of the Joan of Arc Suffrage League, which had just made her an honorary member. It was an awkward encounter for Bernhardt was appalled. While claiming to never talk politics, later that day she told reporters that women were inferior to men and concluded, “In France there are no suffragists because women don’t take the subject seriously.”[1]

- Here is Mrs. Nellie van Slingerland vice-president of the Joan of Arc Suffrage League, holding a pennant after the League’s disastrous rejection at the docks.

- Bernhardt would return to the US in December 1912 to perform on the vaudeville stage. Upon her arrival she reiterated her disapproval of militant suffragettes.

- Women are too emotional and foolish to have the vote. And the militants in London are fools. Nevertheless, she was eager to get to know Americans better. And, indeed she did.

10. When Mme Bernhardt returned to New York on May 4th, 1913, she was asked her opinion of the Women’s Suffrage Parade up 5th Avenue, which had occurred the previous day. And the Divine Sarah responded “I think it is a shame that women do not have the vote. They are educated and capable of understanding politics and the proper methods of government. I read that women in London are burning down houses and blowing up catules. Well, why not let them have the vote?”

- 11. This project got started when I was asked to write something for a catalog on the 1913 Armory Show. And I was curious about the women artists in the show and soon discovered the amazingly complicated politics, which no one had discussed. The Armory Show was organized by the Association of American Painters and Sculptors, all of whom were men. Now looking outside the frame of the Armory Show, it turned out that there were three rival shows going on simultaneously with the Armory Show. Two were all women shows—one by the Women’s Art Club.

- 12. One key figures in this complicated story was Robert Henri—leading light of the Ash Can School who in the 1890s and early 1900s demanded unmitigated realism–– a masculine art against the all too feminine qualities of Impressionism. Many of his artist friends and protégés organized the AAPS, even though his involvement has been described as puzzling and apparently ineffective.

- 13. But Henri’s gender politics were going through important changes, which was becoming evident by 1910. And it was not just Henri’s politics. When it came to the Armory Show, the Domestic Exhibits Committee, head by William Glackens, was accepting unsolicited work for possible inclusion. Henri urged all his women students to submit their work. And of 125 artists who submitted to the open call, 40 were women. Of those 125 artists, 62 were accepted—just under half. And of the 40 women, 20 were accepted though two more ended up in the show through other means. Clearly this was a display of gender neutrality and represented over 40% of the total women artists in the show. Glackens, his wife-painter Edith Dimock, their son and her mother all marched in the 1913 suffrage parade.

14. The politics of feminism were complicated. None of the women in the Woman’s Art Club Show or the all-woman’s show at the McDowell Club showed work at the Armory Show. Artists had to choose sides. So I am particularly interested in cross overs like Abastenia St. Leger Eberle, who had been active in the Woman’s Art Club and showed regularly in that organization’s annual exhibitions. The WAC had awarded Eberle a “Friend of the Club Prize” in 1908. Her sculpture in general was consistent with the middle of the road styles of the WAC. But she accepted an offer to appear in the Armory Show…

- 15. and promptly sculpted The White Slave. This proved one of the most controversial pieces of the Armory Show, rivaling Marcel DuChamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase. Clearly the Woman’s Art Club jury would never have accepted it. Correspondingly painter Hilda Belcher declined to be in the Armory Show and showed in the Woman’s Art Club exhibition. Her mother had been a long-standing member of the WAC. BTW, the Woman’s Art Club changed its name to the Association of Women Painters and Sculptors in April 1913. Just to underscore that the AAPS was really the Association of Male Painters and Sculptors.

- 16. My third Chapter is on Mary Johnston who wrote the most successful best seller between Uncle Tom’s Cabin and Gone with the Wind: To Have and to Hold (1900). From a Virginia family—her father was Major John W Johnston and his cousin was general Joseph E. Johnston, she had become an active feminist and suffragist by 1909, writing The Status of Women for the Equal Suffrage League of Virginia. In 1910 and 1911 she published two-part novel about the Civil War, in which she clearly takes on a masculine genre. That is, they are about battles and troop maneuvers. The women characters are strong but decidedly secondary.

- 17. Her 1913 novel Hagar was marketed as a feminist novel. It is also a roman a clef. Hagar, the female protagonist, is very much like Mary Johnston herself but writes short stories instead of novels. It is a coming of consciousness story.

18. My fourth chapter is about motion pictures and the rise of women as producers and directors in New York and Hollywood in the early 1910s. Alice Guy Blaché, who had been making movies in Paris for Gaumont since 1896, started the Solax Film company in the US in 1910. By 1913 it had become a prosperous company with a large studio in Fort Lee, NJ. She seemingly established a completely equal relationship with her husband. They alternated producing and directing films for the company. By decade’s end this model relationship had unraveled. The other major figure is Lois Weber who emerged as a movie star ca 1910 and then emerged as an important writer-director by 1912-13. She too worked collaborative with her husband, Philip Smalley, though that relationship also unraveled at about the same time.

- 19. My final chapter looks at Floyd Dell, who was a literary critic in Chicago from about 1909 to 1913 before moving to New York City. He wrote a series of articles about prominent feminists in 1912 for the Friday Literary Review in Chicago Post.

20. which became Women as World Builders: Studies in Modern Feminism when it was published in 1913. Among other things I wonder if he wrote about Bernhardt, the Armory Show, Mary Johnston or the movies.

[1] “Greet Bernhardt Here Like a Queen,” New York Times, 30 October 1910, 13; “Bernhardt Sails; Coming Back in 1915,” New York Times, 23 June 1911, 11.