There are the the aftermaths of Birth and Death. The baby coming home from the hospital has its counterpart in the funeral. Later there are rituals of a certain symmetry: memorials and baptisms. I confess a certain personal ambivalence about both. One quality they share: the person being baptized or memorialized is either too young or too inert to protest in either instance. Recently I have been going to more memorials than I would like (the third, not discussed here was Paul Robeson, Jr.’s). At the same time, they were ones I would not have missed.

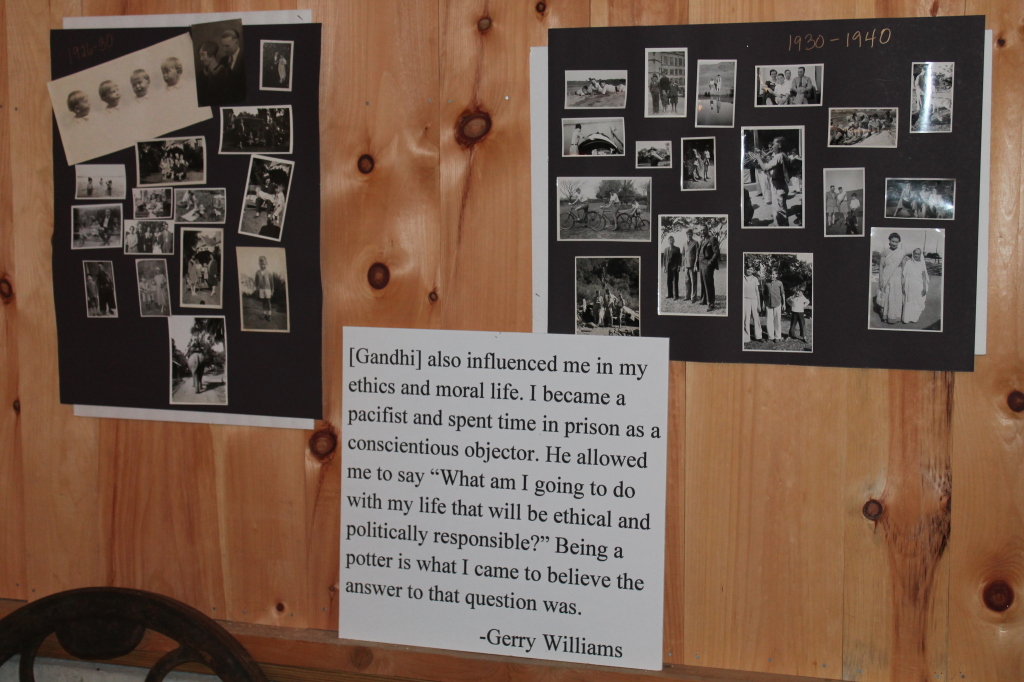

October 18th. I arrived at the Gerry William’s memorial 20 minutes late. There were many reasons hovering in the background. Many parts of the afternoon were certain to be painful. I had also formed a different idea of what was going to happen from the invitation. I imagined people would be eating pot luck food and exchanging stories–as if nothing had changed very much since I first met Gerry at one of his Christmas parties/pottery sales in December 1968. But in death Gerry preeminence partially constrained his style. That idea was not lost (a few of us did bring our pot luck contributions), but it was done more formally than expected. The memorial service was well underway when I arrived. Just as I was sneaking in, the fourth or fifth speaker (Jon Keenan) was explaining to the assembled crowd that “I met Gerry after seeing Charlie Musser’s documentary on Gerry.” Apparently, he was not alone. So it made me ask (again) what did this documentary do? (And what more generally do documentaries do?) How did it change things.

October 18th. I arrived at the Gerry William’s memorial 20 minutes late. There were many reasons hovering in the background. Many parts of the afternoon were certain to be painful. I had also formed a different idea of what was going to happen from the invitation. I imagined people would be eating pot luck food and exchanging stories–as if nothing had changed very much since I first met Gerry at one of his Christmas parties/pottery sales in December 1968. But in death Gerry preeminence partially constrained his style. That idea was not lost (a few of us did bring our pot luck contributions), but it was done more formally than expected. The memorial service was well underway when I arrived. Just as I was sneaking in, the fourth or fifth speaker (Jon Keenan) was explaining to the assembled crowd that “I met Gerry after seeing Charlie Musser’s documentary on Gerry.” Apparently, he was not alone. So it made me ask (again) what did this documentary do? (And what more generally do documentaries do?) How did it change things.

Documentaries can have all sorts of impacts––big and small. The film bound Gerry and me together in its making, and it bound me not just to him but also to his family. He became a surrogate father and perhaps at times I was a surrogate son. Even as I planned the film, it gave me a chance to watch Gerry closely and for long periods of time. As I got ready to make the film, I would just hang out at his studio. Mostly I watched what he was doing (making notes) but we also talked about his philosophical principles and potmaking as a way of being. Not that these were unfamiliar but they became richer and clearer. I would like to think that I absorbed some ethical understandings in the eight years between meeting Gerry and finishing the film, and that these lessons learned have contributed to the way I approach people in my work: how I treat the subjects of my films and essays, how I deal with students, and so forth.

As this memorial confirmed yet again, it helped to create a community out of far flung members. Some people who saw An American Potter went out of their way to see him and some came to the Phoenix Workshops that he ran in the summer.

The filming took three weeks to shoot and in those weeks, the understanding was that making the film took priority over making pots. I paid Gerry $300 a week and there was some deferred payment as well but he did a lot of things (the wet firing that opens the film) that cost money for which there was no return. In some respects, I was undoubtedly presumptuous. I was a 26-year-old first-time filmmaker. Truth be told, there was little reason to have confidence about how the film would turn out. Basically he agreed to make the film as an act of generosity.

People were quite pleasantly surprised when they actually saw it. I remember wanting to premiere the documentary in the local Currier Gallery of Art in Manchester. I had met the director David Brooke, probably at an exhibition of Gerry’s pottery. He was quite reluctant–until he saw the film. The film went on to win various awards and it probably helped Gerry’s career in certain modest ways. Certainly it helped to build this community of admirers and friends. And, as I have already said, it became a bond between us. Gerry liked the film and apparently would sometimes take it with him to show people. It was a way to show off his studio and his work. One person, who appeared in the film but was not at the memorial, came to a different conclusion: that the film became a kind of trap for Gerry. The film did not change and what people saw of Gerry was too often what they saw in the film. I don’t think that is entirely true–entirely fair to Gerry or to the film–but I am sure there was an element of truth to that. It is also true that the documentary I recently made of Errol Morris reworks many of the underlying elements of this film. Does that make he a candidate for an auteurist study? Or does it mean I too am somehow stuck?

When Gerry got ill and suffered from a combination of Parkinsons and Alzheimers, the film took on a new significance. Of course there are many ways in which we can remember Gerry–through his pots and other forms of expression (including of course his work as editor of Studio Potter Magazine). His daughter Shelly is beginning to write a biography. But the film, which has Bazinian elements (long takes) has become Bazinian in a different way. It is as AB suggested a kind of death mask. The person who is lost to us is there in front of us, reminding us with considerable force what we have lost. It captured a moment in time when Gerry was at the peak of his creative powers. The disconnect between Gerry in the film and in his increasingly enfeebled state was certainly emotionally fraught. Indeed, just before leaving for the memorial, I spot checked a couple of DVDs that I thought I better bring along in case they were needed. It started the day in an emotional vein. It is still almost impossible for me to watch the film without weeping.

But enough about the film. About the memorial. One thing that happens at memorials is that one sees people one has not seen in a long time or often for the first time. I had been in touch with potter and ceramics professor Jay Lacouture, who teaches at Salve Regina University in Newport, Rhode Island, on email.

He is planning a Williams retrospective at his gallery and was hoping I could come to introduce the film. (It is the same weekend as the Society for Cinema and Media Studies Conference in Montreal and unfortunately this might not be possible.) So we had a chance to finally meet.

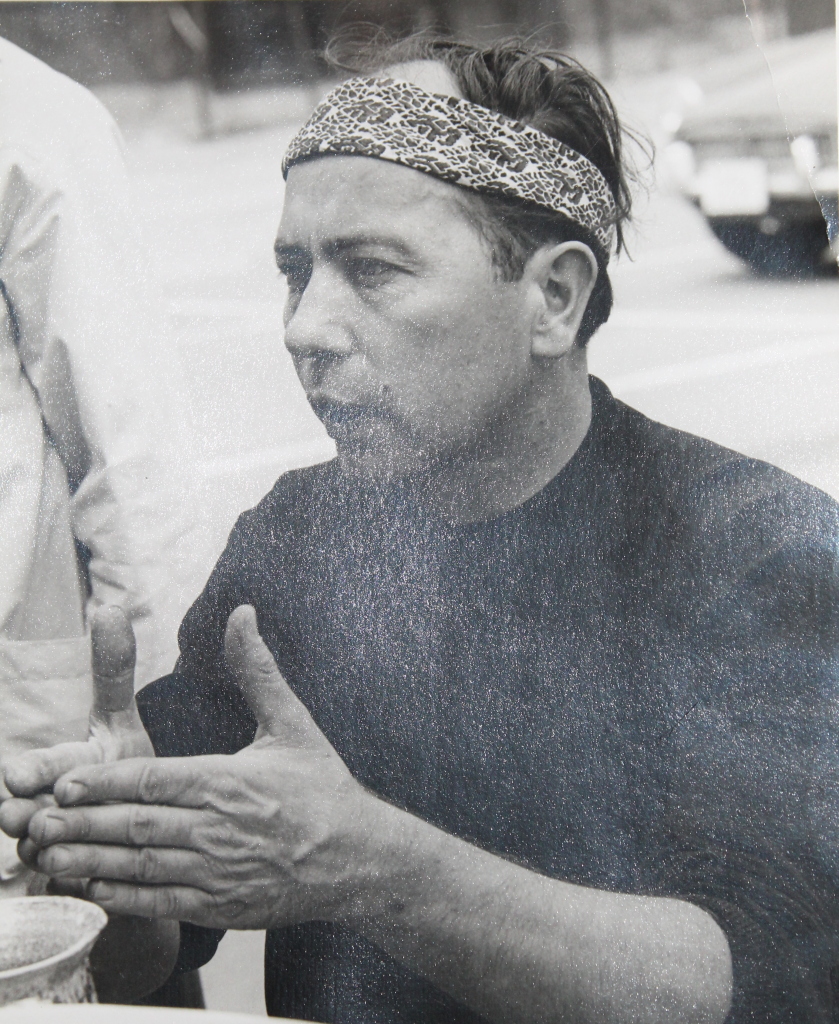

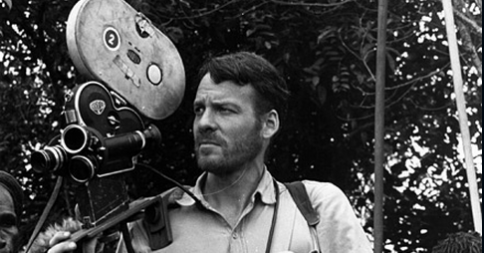

In truth, I was not so up for talking. I spent much of the time looking at the photos of Gerry’s life. I had not seen Bill Finney’s photo of Gerry in a long time. It reminded me that Gerry had some untapped potential as a fashion model. It is interesting and now regrettable that I did not think to have any pictures taken of the two of us. But there was unexpected find on those walls–a picture of me with Julie Williams (surrogate mom).

It is interesting and now regrettable that I did not think to have any pictures taken of the two of us. But there was unexpected find on those walls–a picture of me with Julie Williams (surrogate mom).

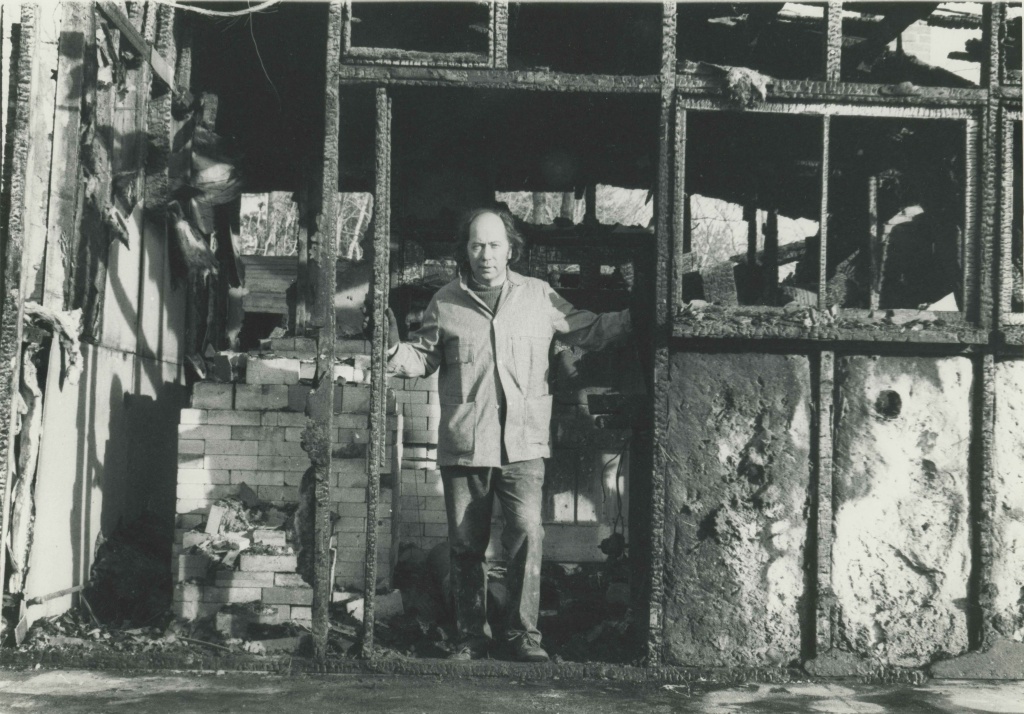

As a kind of post-script. Today when I was cleaning up my office I found a box of photographs that had gone missing for awhile. They included photos I had used in An American Potter, of his burned studio and its rebirth through local support (thus the Phoenix Workshops). As Gerry said in the film, the only thing comparable to the destruction of his studio was a death in the family.

***

The following weekend I left behind the history that surrounds my first (non-student) film and turned to my current project, Visa Wives (working title) I am making with my wife Threese.

October 25th: Threese, John Carlos and I went to St. Louis attend the baptism of our nephew (JCs’s cousin) Francis Braulio Serana McGinnis. His mom, Cathy (aka Cheerful) Serana McGinns is Threese’s sister. Part of the excitement was that Father Chester, Cathy’s twin brother, was coming from Cebu to perform the baptism.

They are key figures in our documentary Visa Wives so inevitably, we brought our camera. Making a film about family has some decided benefits. All too often work takes one away from family. In this case, it bring us closer. I did most of the shooting since Threese was often caught up in other responsibilities.These photos were taken by a friend Stephen hired to document the occasion.

They are key figures in our documentary Visa Wives so inevitably, we brought our camera. Making a film about family has some decided benefits. All too often work takes one away from family. In this case, it bring us closer. I did most of the shooting since Threese was often caught up in other responsibilities.These photos were taken by a friend Stephen hired to document the occasion.

Although in some ways it kept me more at the edges, it also kept me much more attentive and engaged. I could imagine attending the baptism and hovering politely in the background. Instead, I was entirely focused on the ceremony, the people attending, even the church itself.

Although in some ways it kept me more at the edges, it also kept me much more attentive and engaged. I could imagine attending the baptism and hovering politely in the background. Instead, I was entirely focused on the ceremony, the people attending, even the church itself.

Although there was some low key suggestions that John Carlos might also participate in the baptismal event, this did not happen for a variety of reasons. First JC’s sister Hannah Grace Zeavin Musser (aka Hannah Zeavin) is a nice Jewish girl. My great grandfather was a Protestant minister though his son (John Musser) stole the clapper from the bell that was donated in his father honor to the prep school he was attending. He married my grandmother but since they were not from the same Protestant denomination, the ministers from either side refused to marry them. There has been a certain degree of distance from any sort of organized religion from that side of the family ever since. And then again, John Carlos’s second mother –Subiya––is a former Hindu who married a Muslim. John Carlos may have gone to mosque more often than to church. Finally when the question was put to John Carlos, he wondered why children needed to baptized since they all come from God. Well… we’ll let him sort that out in the years ahead.

This trip was good in other ways as well. Stephen and I got to compare notes on fatherhood and being married into the Serana family. At the moment Stephen is actually a stay at home dad while Cathy goes to work in the hospital where she is a nurse. He is planning to go back to work in September and they will reorganize their work-life schedule then. It will be interesting to see how reality conforms to their wishes. In any case, Stephen and I connected in a good way, and Threese filmed one of our conversations after Cathy went to work and while Francis (named after Pope Francis) was napping and John Carlos went to get cookies and perhaps a little religious education from his uncle.

***

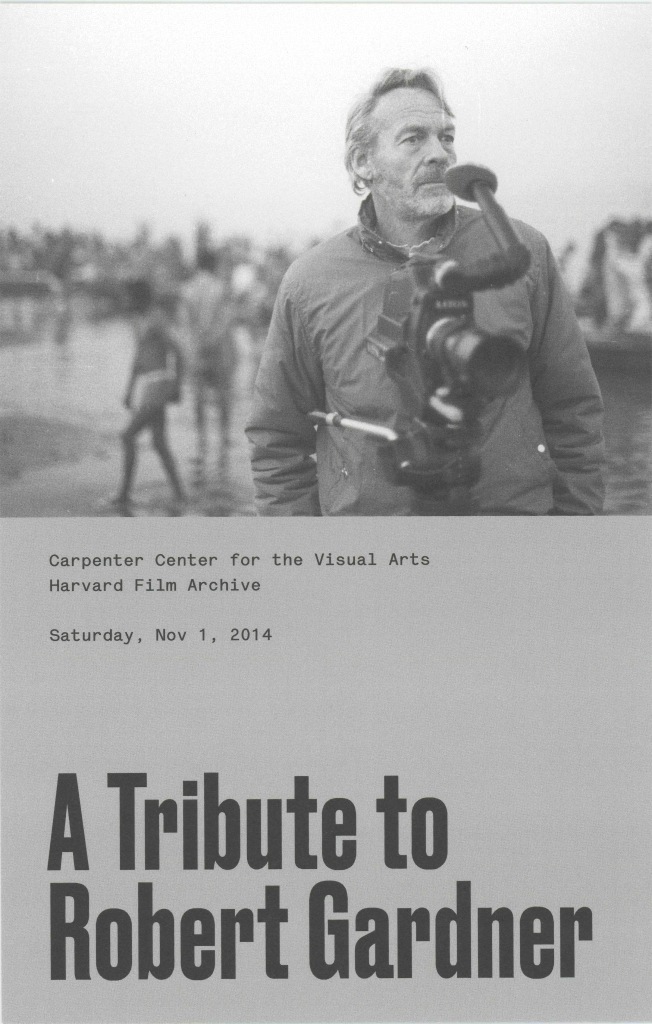

I have had a long, friendly though certainly attenuated relationship with Robert Gardner. It began really when I was taking my first film class with Jay Leyda in the Fall of 1970. It stuck with me. I saw him again when I was being interviewed for a job at Harvard which I did not get (though I was told he had been a supporter). And I brought him to Yale to show a series of his films, including Dead Birds: in fact, the Yale Film Study Center subsequently bought a 35mm print of Dead Birds as a result of that visit. Finally I have been writing a lengthy article entitled “First Encounters: An Essay on Dead Birds and Robert Gardner,” Dead Birds was a film that stayed with me all these years, and I have been intermittently distressed at the ways in which the film has been denigrated, particularly by Jay Ruby and his circle. So given the chance, I finally decided to write about it. I think the essay makes some important points. In the process of the writing, I would correspond with Robert via email. It was a friendly exchange. Mostly I asked for information but I also told him about the rather personal nature of what I was doing. I was planning to email a couple of last questions when Charles Warren informed me that he had died, quite unexpectedly. I was a little stunned. I had a sense that my effort were fostering a more intimate relationship, and everything felt cut short. Not least of all, of course his life. And in this sense his death was quite different than Gerry Williams’ death, which ended a life that had become painfully degraded.

Dead Birds was a film that stayed with me all these years, and I have been intermittently distressed at the ways in which the film has been denigrated, particularly by Jay Ruby and his circle. So given the chance, I finally decided to write about it. I think the essay makes some important points. In the process of the writing, I would correspond with Robert via email. It was a friendly exchange. Mostly I asked for information but I also told him about the rather personal nature of what I was doing. I was planning to email a couple of last questions when Charles Warren informed me that he had died, quite unexpectedly. I was a little stunned. I had a sense that my effort were fostering a more intimate relationship, and everything felt cut short. Not least of all, of course his life. And in this sense his death was quite different than Gerry Williams’ death, which ended a life that had become painfully degraded.

In any case I felt it important to go to Robert’s memorial–to connect with other people who knew him–and also learn some more about his life.