“Charles Sheeler and Paul Strand: Friends, Collaborators, Rivals,” in Kirsten M. Jensen, ed., Charles Sheeler: Fashion, Photography and Sculptural Form (Doylestown, PA: James Michener Art Museum, 2017) 155-177. I have often wanted to write about Strand and Sheeler’s Manhatta (1921) but needed an occasion. Finally, happily one came along–many thanks to Kirsten Jensen. I think this essay breaks new ground by placing the short film in the larger context of the Sheeler-Strand association, their respective histories and their body of photographic work. Plus the essential historical context of World War I, which both quietly opposed. Serendipitous research proved crucial. Rather than rehash my analyses here, just take a look at my essay: Prof Musser,Sheeler&Strand.

“Charles Sheeler and Paul Strand: Friends, Collaborators, Rivals,” in Kirsten M. Jensen, ed., Charles Sheeler: Fashion, Photography and Sculptural Form (Doylestown, PA: James Michener Art Museum, 2017) 155-177. I have often wanted to write about Strand and Sheeler’s Manhatta (1921) but needed an occasion. Finally, happily one came along–many thanks to Kirsten Jensen. I think this essay breaks new ground by placing the short film in the larger context of the Sheeler-Strand association, their respective histories and their body of photographic work. Plus the essential historical context of World War I, which both quietly opposed. Serendipitous research proved crucial. Rather than rehash my analyses here, just take a look at my essay: Prof Musser,Sheeler&Strand.

“First Encounters: An Essay on Dead Birds and Robert Gardner,” in Rebecca Meyers, William Rothman, and Charles Warren, eds. Looking with Robert Gardner (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2016), 143-170. This is an essay about my relationship to Dead Birds and with Robert Gardner. That relationship was most in my head but one of the great pleasure of working on this essay was to be able to correspond with Robert when I had a question. Then he died unexpectedly. Of course, I still had questions. It also got me thinking about the essay film. Dead Birds has been critically attacked from many perspectives; but when understood as an essay film, those criticisms prove illusory. Musser, Gardner_essay_on DeadBirds

“First Encounters: An Essay on Dead Birds and Robert Gardner,” in Rebecca Meyers, William Rothman, and Charles Warren, eds. Looking with Robert Gardner (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2016), 143-170. This is an essay about my relationship to Dead Birds and with Robert Gardner. That relationship was most in my head but one of the great pleasure of working on this essay was to be able to correspond with Robert when I had a question. Then he died unexpectedly. Of course, I still had questions. It also got me thinking about the essay film. Dead Birds has been critically attacked from many perspectives; but when understood as an essay film, those criticisms prove illusory. Musser, Gardner_essay_on DeadBirds

“Early Advertising and Promotional Films, 1893-1900: Edison Motion Pictures as a Case Study,” in Bo Florin, Nico de Klerk and Patrick Vonderau, eds., Films That Sell: Moving Pictures and Advertising (London: BFI Palgrave, 2016), 83-90. Much of this was excerpted from my introductory essay in Edison Motion Pictures, 1890-1900. But this provides a new context for thinking about advertising and promotion as a crucial function of cinema in the 1890s. Musser,Early_Advertising&promotionalfilms

“Early Advertising and Promotional Films, 1893-1900: Edison Motion Pictures as a Case Study,” in Bo Florin, Nico de Klerk and Patrick Vonderau, eds., Films That Sell: Moving Pictures and Advertising (London: BFI Palgrave, 2016), 83-90. Much of this was excerpted from my introductory essay in Edison Motion Pictures, 1890-1900. But this provides a new context for thinking about advertising and promotion as a crucial function of cinema in the 1890s. Musser,Early_Advertising&promotionalfilms

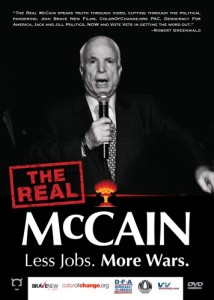

“Political Documentary, YouTube and the 2008 US Presidential Election: Focus on Robert Greenwald and David N. Bossie,” Studies in Documentary Film 4:1 (2010), 199-210. This article looks at the ways in which new media forms and older media practices were mobilized in the 2008 election. Specifically Robert Greenwald and Brave New Films made a series of highly influential documentaries that impacted on the 2004 presidential elections (e.g. Uncovered: The Truth About the Iraq War (2003) and Outfoxed: Rupert Murdoch’s War on Journalism (2004)). They continued to produce documentaries relevant to the political campaigns of 2006 with Iraq for Sale: The War Profiteers (2006) but then abandoned the feature-length documentary as a form in 2008 and shifted to making short campaign videos such as McCain’s Mansions, available on YouTube and his own internet websites. David Bossie and Citizens United, in contrast, were playing desperate catch up to Greenwald when it came to documentaries in 2004 election cycle. They were better prepared in 2006 with such efforts as Kevin Knoblock’s Border War: The Battle Over Illegal Immigration. Bossie continued to put his energies into feature-length documentaries in 2008, notably with Hillary: The Movie (2008) and then Hype: The Obama Effect (2008) while having a poor Internet presence. Greenwald’s efforts (McCain’s Mansions were part of “The Real McCain” series) were illustrative of a larger embrace of the Internet by the Obama campaign that arguably did much to help him win him the Democratic Party nomination for President and then persevere in the 2008 election. The essay here, Musser,PoliticalDocumentary, YouTube&2008Presidential_Election, is looking toward one of the books on which I am working, entitled Media Shifts and the US Presidential Elections: Stereopticon/ Cinema/Television/Internet.

“Political Documentary, YouTube and the 2008 US Presidential Election: Focus on Robert Greenwald and David N. Bossie,” Studies in Documentary Film 4:1 (2010), 199-210. This article looks at the ways in which new media forms and older media practices were mobilized in the 2008 election. Specifically Robert Greenwald and Brave New Films made a series of highly influential documentaries that impacted on the 2004 presidential elections (e.g. Uncovered: The Truth About the Iraq War (2003) and Outfoxed: Rupert Murdoch’s War on Journalism (2004)). They continued to produce documentaries relevant to the political campaigns of 2006 with Iraq for Sale: The War Profiteers (2006) but then abandoned the feature-length documentary as a form in 2008 and shifted to making short campaign videos such as McCain’s Mansions, available on YouTube and his own internet websites. David Bossie and Citizens United, in contrast, were playing desperate catch up to Greenwald when it came to documentaries in 2004 election cycle. They were better prepared in 2006 with such efforts as Kevin Knoblock’s Border War: The Battle Over Illegal Immigration. Bossie continued to put his energies into feature-length documentaries in 2008, notably with Hillary: The Movie (2008) and then Hype: The Obama Effect (2008) while having a poor Internet presence. Greenwald’s efforts (McCain’s Mansions were part of “The Real McCain” series) were illustrative of a larger embrace of the Internet by the Obama campaign that arguably did much to help him win him the Democratic Party nomination for President and then persevere in the 2008 election. The essay here, Musser,PoliticalDocumentary, YouTube&2008Presidential_Election, is looking toward one of the books on which I am working, entitled Media Shifts and the US Presidential Elections: Stereopticon/ Cinema/Television/Internet.

I’ve been thinking about some of these issues quite a bit this semester, particularly as I screened Davis Guggenheim’s An Inconvenient Truth (2006) with Al Gore for my course on Documentary and the Environment. An Inconvenient Truth, like Iraq for Sale, helped the Democrats take back the House of Representatives; but it, along with other eco-docs such as Who Killed the Electric Car? (2006), did much to further polarize environmental issues along Democrat-Republican party lines. At the same time, as I think back to that period, An Inconvenient Truth regained some respect and appreciation for Gore among the Democratic faithful, many of whom––like me––were deeply angry at him for blowing the 2000 election. Perhaps this redemption was necessary, but the further polarization around issues such as global warming and climate change have been an unfortunate by-product.

“Cameras at Coney, 1940-1953,” in Robin Jaffee Frank, ed., Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland (Yale University Press, 2015), 228-247. Little by little, and for different reasons, I have been researching and writing about American culture of the 1940s. (My work on Carl Marzani and Union Films are another aspect of this.) I have been involved in this Coney Island project from an early stage and lobbied for the opportunity to write a catalog essay on films made in the immediate post-World War II era. I had a sense that there was something interesting to explore in this moment but was not sure what I would find or what shape it would take. I had a sense that there was an interesting relationship between film and photography at this moment, but little more. There is always the excitement–and perhaps the anxiety––of taking on a new topic. My mandate was to focus on three films in particular: Weegee’s New York (1948), which incorporated two short films, one of which was entitled Coney Island; Coney Island, USA (1951), which was directed by Sherry Valentine; and Morris Engel’s Little Fugitive (1953). As it turned out Coney Island, USA was shot by photographer Carroll Siskind and all three cinematographers (Siskind, Weegee and Engel) had been actively photographing in Coney Island in the early 1940s, were all members of the Photo League and, not surprisingly, knew each other. The result is an interesting catalog essay, Musser,Cameras_at_Coney, of which I am quite proud. I was able to interview a couple of survivors from that era, who threw valuable light on Coney Island, USA in particular. But all in all, it was a pleasure to work with Robin Jaffee Frank, who curated this show which opened at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art in Hartford, CT., at the end of January 2015. Moreover, the catalog, most of which she wrote and otherwise supervised, is an impressive achievement. Thank you, Robin!

“Cameras at Coney, 1940-1953,” in Robin Jaffee Frank, ed., Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland (Yale University Press, 2015), 228-247. Little by little, and for different reasons, I have been researching and writing about American culture of the 1940s. (My work on Carl Marzani and Union Films are another aspect of this.) I have been involved in this Coney Island project from an early stage and lobbied for the opportunity to write a catalog essay on films made in the immediate post-World War II era. I had a sense that there was something interesting to explore in this moment but was not sure what I would find or what shape it would take. I had a sense that there was an interesting relationship between film and photography at this moment, but little more. There is always the excitement–and perhaps the anxiety––of taking on a new topic. My mandate was to focus on three films in particular: Weegee’s New York (1948), which incorporated two short films, one of which was entitled Coney Island; Coney Island, USA (1951), which was directed by Sherry Valentine; and Morris Engel’s Little Fugitive (1953). As it turned out Coney Island, USA was shot by photographer Carroll Siskind and all three cinematographers (Siskind, Weegee and Engel) had been actively photographing in Coney Island in the early 1940s, were all members of the Photo League and, not surprisingly, knew each other. The result is an interesting catalog essay, Musser,Cameras_at_Coney, of which I am quite proud. I was able to interview a couple of survivors from that era, who threw valuable light on Coney Island, USA in particular. But all in all, it was a pleasure to work with Robin Jaffee Frank, who curated this show which opened at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art in Hartford, CT., at the end of January 2015. Moreover, the catalog, most of which she wrote and otherwise supervised, is an impressive achievement. Thank you, Robin!

“The Environmental Documentary and the Contemporary Moment,” in Anil Narine, ed., Eco-Trauma Cinema (New York: Routledge, 2015), 46-71. This essay came about casually enough. One of my book projects, which one day might still reach completion, is entitled Truth and Documentary in the Age of George W. Bush. It ends with a group of environmental documentaries that were being screened at the Sundance Film Festival in January 2009 as Barack Obama was being sworn into office as our new President. These include Joe Berlinger’s Crude (2009), Robert Stone’s Earth Days (2009), Dirt!: The Movie (directed by Bill Benenson, Gene Rosow and Eleonore Daily; 2009), Rupert Murray’s The End of the Line (2009), John Maringouin’s Big River Man (2009), and Louie Psihoyos’s The Cove (2009). I decided to sketch this out in a Society for Cinema and Media Studies (SCMS) presentation, particularly since I was in the process of teaching a course on Documentary and the Environment. Anil Narine attended my presentation and asked to include it in his collection of essays on Eco-Trauma Cinema. I agreed and it went through a series of substantial revisions. Anil also pushed me is useful ways to think about many of these documentaries in terms of trauma–and the relations between the tropes of documentary truth and the traumatic experience of documentary subjects in many of these films. So Documentary_and_the_Contemporary_Moment now comes out as I am teaching Documentary and the Environment a second time around.

“The Environmental Documentary and the Contemporary Moment,” in Anil Narine, ed., Eco-Trauma Cinema (New York: Routledge, 2015), 46-71. This essay came about casually enough. One of my book projects, which one day might still reach completion, is entitled Truth and Documentary in the Age of George W. Bush. It ends with a group of environmental documentaries that were being screened at the Sundance Film Festival in January 2009 as Barack Obama was being sworn into office as our new President. These include Joe Berlinger’s Crude (2009), Robert Stone’s Earth Days (2009), Dirt!: The Movie (directed by Bill Benenson, Gene Rosow and Eleonore Daily; 2009), Rupert Murray’s The End of the Line (2009), John Maringouin’s Big River Man (2009), and Louie Psihoyos’s The Cove (2009). I decided to sketch this out in a Society for Cinema and Media Studies (SCMS) presentation, particularly since I was in the process of teaching a course on Documentary and the Environment. Anil Narine attended my presentation and asked to include it in his collection of essays on Eco-Trauma Cinema. I agreed and it went through a series of substantial revisions. Anil also pushed me is useful ways to think about many of these documentaries in terms of trauma–and the relations between the tropes of documentary truth and the traumatic experience of documentary subjects in many of these films. So Documentary_and_the_Contemporary_Moment now comes out as I am teaching Documentary and the Environment a second time around.

“Another Look at the ‘Chaser Theory,” Studies in Visual Communication 10:4 (November 1984), 24-44+. Here’s an “oldie but goodie.” I actually have tried to put it aside, thinking that the battle was won. However, I had my students read Robert C. Allen’s article, also from long ago, “Contra the Chaser Theory,” in John Fell, ed., Film Before Griffith (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983) pp 144-152. I did this after having imposed my book The Emergence of Cinema on them. Without directly going after Allen, The Emergence of Cinema make it pretty clear that there was a “chaser period” between roughly 1901 and 1903 and for a lot of reasons. In particular, Edison managed to shut down most film production in the US outside his own company, putting the industry in crisis (Sigmund Lubin apparently moved to Europe––or moved the remnants of his motion picture business––to escape Edison’s legal wrath.) My idea was that my students would discern the two conflicting arguments and then try to make sense of them. However, they somehow did not realize that Allen’s version of events and my version were at odds. They found his arguments quite logical. So I dusted off this essay and sent it to them as an email attachment. So you get it as well. As the first several pages of the article make clear, much more than “the chaser period” is at stake. Read: AnotherLookattheChaserTheory

“The Devil’s Parody: Horace McCoy’s Appropriation and Refiguration of Two Hollywood Musicals.” in Robert Stam and Alessandra Raengo (eds). A Companion to Literature and Film (Blackwell Publishing, 2004), 229-257.

“The Devil’s Parody: Horace McCoy’s Appropriation and Refiguration of Two Hollywood Musicals.” in Robert Stam and Alessandra Raengo (eds). A Companion to Literature and Film (Blackwell Publishing, 2004), 229-257.

I love this essay, which makes some key connection and dissects the elements of appropriation (a form of adaptation) in smart ways. But while it is quite polished, it was finished prematurely. To really get to the guts of what McCoy was doing, one has to link it to What Price Hollywood? (George Cukor, 1932) as well. The film was just very hard to see back when I was working on this. So this is a shortcoming, a failure of sorts. But the method is well there for those who want to give the essay a chance. The derbies at the Marathon dance where Robert and Gloria go to be discovered in They Shoot Horses Don’t They? echo the Brown Derby where Mary Evans is trying to get her break, where she is hoping to be seen and discovered–indeed is seen and discovered. So McCoy’s novel has three key film antecedents, not two. Sigh. When am I going to write that book on the Hollywood novel and the Hollywood film. Just wait. Musser,Devil’sParody, HoraceMcCoy

“Problems in Historiography: The Documentary Tradition Before Nanook of the North,” in Brian Winston, ed., The British Film Institute Companion to Documentary (London: BFI/Palgrave MacMIllan, 2013), 119-128. I took my first critical studies course in documentary with Brian Winston at NYU; finally, some 35 years later, I contributed to this anthology which he assembled. Basically this article argues that the documentary has had a long and rich history long before the appearance of Nanook of the North, which is often identified as constituting the crucial film in the formation of modern documentary practice. For those who have read the first chapter of The Emergence of Cinema, this argument will be a familiar. However, I try to think through this trajectory while attending to the relationship between genre (or mode) and media specificity. The move from film to video underscores the fact that documentary is not a film genre per se. Nor is it hard to imagine a documentary that is composed entirely of photographs, which is, in fact, what the illustrated lecture was in the second half of the 19th century–or at least the ones that used the magic lantern or stereopticon (ie. “stereopticon lectures”). Particularly in the present era, when we have no problem acknowledging the legitimacy of animated documentaries such as Waltzing with Bashir, the history of the documentary–or what might more properly be called “the documentary tradition,” needs some further reflection, historical research and conceptualization. Documentary-like programs preceded the era of photography and may go back to the seventeenth century and the earliest days of the magic lantern (if not possibly even before). The second part of the essay offers a highly condensed account of one of the most long-standing documentary genres, which focuses on war, from the Crimean War to the First World War. Take a look: DocumentaryHistoriography,BeforeNanook.

“Problems in Historiography: The Documentary Tradition Before Nanook of the North,” in Brian Winston, ed., The British Film Institute Companion to Documentary (London: BFI/Palgrave MacMIllan, 2013), 119-128. I took my first critical studies course in documentary with Brian Winston at NYU; finally, some 35 years later, I contributed to this anthology which he assembled. Basically this article argues that the documentary has had a long and rich history long before the appearance of Nanook of the North, which is often identified as constituting the crucial film in the formation of modern documentary practice. For those who have read the first chapter of The Emergence of Cinema, this argument will be a familiar. However, I try to think through this trajectory while attending to the relationship between genre (or mode) and media specificity. The move from film to video underscores the fact that documentary is not a film genre per se. Nor is it hard to imagine a documentary that is composed entirely of photographs, which is, in fact, what the illustrated lecture was in the second half of the 19th century–or at least the ones that used the magic lantern or stereopticon (ie. “stereopticon lectures”). Particularly in the present era, when we have no problem acknowledging the legitimacy of animated documentaries such as Waltzing with Bashir, the history of the documentary–or what might more properly be called “the documentary tradition,” needs some further reflection, historical research and conceptualization. Documentary-like programs preceded the era of photography and may go back to the seventeenth century and the earliest days of the magic lantern (if not possibly even before). The second part of the essay offers a highly condensed account of one of the most long-standing documentary genres, which focuses on war, from the Crimean War to the First World War. Take a look: DocumentaryHistoriography,BeforeNanook.

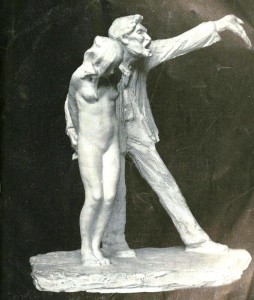

“1913: A Feminist Moment in the Arts,” Marilyn Kushner, Kimberly Orcutt and Casey Blake, eds., The Armory Show at 100: Modernism and Revolution (New-York Historical Society, 2013), 169-179. This essay is in the catalog for the New-York Historical Society Exhibition, which opened on October 11, 2013 (while I was still in Pordenone, Italy). The Armory Show or the International Exhibition of Modern Art is often considered the most important art exhibition in the United States in the 20th Century, introducing Americans to modern art for the first time (with the usual caveats). I was honored and delighted to be asked to write an essay for the catalog. The idea was along the lines of cinema and the Armory Show. The usual, I dare say anticipated piece would consider cinema as a modern art, one that involved the fragmentation of space and time (something that was certainly becoming more common in the 1908-1913 period) and thus the analogy to modernist painting and sculpture. The fact is, that this had already been done rather well by Bernice B. Rose, Tom Gunning, and Jennifer Wild in the catalog Picasso, Braque and Early Film in Cubism (2007). Moreover, I was eager to pursue a somewhat different aspect of motion picture history in the 1912-1913 moment: the significant number of women moving into producing and directing as well as starting their own film companies. There were a substantial number of women artists represented in the Armory Show. So I became interested in possible relationships or parallels between women in both fields of creative endeavor. This was not what they had expected but the show’s curators were encouraging, noting that the catalog did not otherwise have an essay on the women artists in the show.

“1913: A Feminist Moment in the Arts,” Marilyn Kushner, Kimberly Orcutt and Casey Blake, eds., The Armory Show at 100: Modernism and Revolution (New-York Historical Society, 2013), 169-179. This essay is in the catalog for the New-York Historical Society Exhibition, which opened on October 11, 2013 (while I was still in Pordenone, Italy). The Armory Show or the International Exhibition of Modern Art is often considered the most important art exhibition in the United States in the 20th Century, introducing Americans to modern art for the first time (with the usual caveats). I was honored and delighted to be asked to write an essay for the catalog. The idea was along the lines of cinema and the Armory Show. The usual, I dare say anticipated piece would consider cinema as a modern art, one that involved the fragmentation of space and time (something that was certainly becoming more common in the 1908-1913 period) and thus the analogy to modernist painting and sculpture. The fact is, that this had already been done rather well by Bernice B. Rose, Tom Gunning, and Jennifer Wild in the catalog Picasso, Braque and Early Film in Cubism (2007). Moreover, I was eager to pursue a somewhat different aspect of motion picture history in the 1912-1913 moment: the significant number of women moving into producing and directing as well as starting their own film companies. There were a substantial number of women artists represented in the Armory Show. So I became interested in possible relationships or parallels between women in both fields of creative endeavor. This was not what they had expected but the show’s curators were encouraging, noting that the catalog did not otherwise have an essay on the women artists in the show.

In fact, except for a brief introductory overview of women in the arts at this critical moment, I ended up focusing on the Armory Show itself–or rather the New York art scene. The term “feminism” itself became popular in 1913, and one major problem with the Armory Show was that the Association of American Painters and Sculptors, which organized the show, had an all-male membership. Women artists were not amused. While the Kimberly and Marilyn had researchers (those invaluable interns) going through all the newspapers and small journals to cull articles about the Armory Show, I began to read through the newspapers in a more general way to see what was happening with the arts in terms of women’s suffrage and feminism. In fact, I soon discovered that there were three New York art exhibitions that ran in opposition to the Armory Show. One donated its proceeds to the Woman’s Suffrage Union. No members of the AAPS were invited to participate (or allowed). Two other exhbitions were all women shows and none of the women artists in those shows were in the Armory Show. There were also feminist initiatives inside the Armory Show as well, led by a number AAPS members. All this got lost due to the controversies around Cubism and post-Impressionism. Indeed, these important dynamics are not particular evident in the show itself. So read it here!

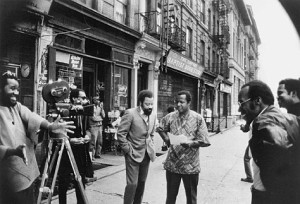

“William Greaves: Chronicler of the Afro-American Experience,” Film Quarterly 45:3 (Spring 1992), 513-25, reprinted in Michael T. Martin, ed., Cinemas of the Black Diaspora : Diversity, Dependence & Oppositionality (Detroit: Wayne State Press, 1995), 389-404 (co-written with with Adam Knee).

“William Greaves: Chronicler of the Afro-American Experience,” Film Quarterly 45:3 (Spring 1992), 513-25, reprinted in Michael T. Martin, ed., Cinemas of the Black Diaspora : Diversity, Dependence & Oppositionality (Detroit: Wayne State Press, 1995), 389-404 (co-written with with Adam Knee).

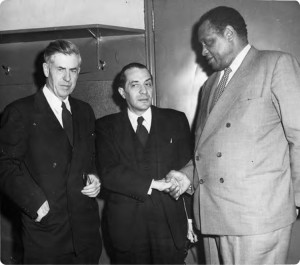

The world is going digital and I find myself making pdf’s of old articles (for a student in this instance). In the process, my memories and affection for the piece often come flooding back. My fellow NYU Ph.D. Adam Knee and I were at some event together when we discovered that each of us was in the relatively early stages of working on an essay about William Greaves. Rather than compete, we collaborated.

I had know Bill since my early days as a filmmaker in New York, when I worked for Amram Nowak as a writer/editor on Sons of Bwiregi (1976), a documentary for the Maryknoll Missionaries. Bill worked next door. Young and naive, I didn’t think much of it. At the time I was more interested in one of his charming young associate producers (who all too obviously had no real interest in me). In short, I didn’t know who Bill Greaves really was.

Of course by 1991, I had come to realize that the guy next door was the legendary “Dean of Black Documentary Filmmaking.” The essay became a way to make amends for my youthful stupidity and learn more about Bill and his career. He enjoyed the process and the results. So did I. Eventually I brought him up to Yale. Bill said that he never left Manhattan for less than $5,000. He was being playfully braggadocious. I am sure I could have gotten him to come for less–a lot less, but I decided to take him seriously–the only time I have done something like that.

For what it is worth, Bill insisted on several occasions that this piece was his favorite article about his own film career. Musser&Knee,_William_Greaves_Essay

“Conversions and Convergences: Sarah Bernhardt in the Era of Technological Reproducibility, 1910-1913,” Film History (Special Issue) 25: nos 1-2, pp 154-174.

This essay was written for a Special Issue of Film History, which signaled the new editorial regime of Greg Waller. Greg asked for a submission, but I didn’t have anything that seemed right for the occasion. However, I was just finishing an essay on women and the art world at the time of the 1913 Armory Show, entitled “A Feminist Moment in the Arts.” It was motivated by a fairly simple question: if feminism seemed to be flourishing in the film world in 1912-1913, what was happening in the other arts? The situation proved far more dynamic and fraught than one might have expected. For some reason, I started my essay off “Sarah Bernhardt missed the Armory Show.” The editors loved the line and I was stuck. First I had to make sure that assertion was correct, and it turned out to be a near thing. She arrived in Chicago only five days after the Chicago Art Institute version of the Armory Show had closed. But I also had to delve into Bernhardt’s gender politics, which again did not conform to my expectations–nor the assessment offered by her biographers. Bernhardt was a well-known anti-suffragette until 1912, then flipped her position over the course of her US vaudeville tour, which ran from December 1912 to May 1913. What then were the relation of her evolving feminism to her artistic practices at the very moment she was emerging as a screen star? A screen star? More like a media star. And once again this demonstrates the ways that a media studies perspective can be productive by providing a different, more expansive research paradigm.

-“The Hidden and the Unspeakable: On Theatrical Culture, Oscar Wilde and Ernst Lubitsch’s Lady Windermere’s Fan (1925),” Film Studies 4 (Summer 2004), 12-47.

-“The Hidden and the Unspeakable: On Theatrical Culture, Oscar Wilde and Ernst Lubitsch’s Lady Windermere’s Fan (1925),” Film Studies 4 (Summer 2004), 12-47.

OK. This is not a recent article but Stephen Neale wrote me this morning (3-27-2013) saying that he heard I had been working on “an article that was never completed” on Lubitsch’s Lady Windermere’s Fan and its relation to the original film adaptation directed by Fred Paul for the Ideal Film Company in 1916. Well, the journal Film Studies, edited by Ian Christie, was relatively short lived and does not seem to be available on line so I thought I better make it available here: Musser,Lady_Windermere’s_Fan_essay. It is one of my favorite articles and a revised version will become a chapter in my book on Theatrical Culture Transformed, 1918-1930.

“Paul Robeson and the End of His ‘Movie’ Career,” in Mia Mask, ed. Contemporary Black American Cinema: Race, Gender and Sexuality at the Movies (New York: Routledge, 2012), 14-39. [an earlier version of this appeared in Cinemas 19:1 (2009), 147-179.]

“Paul Robeson and the End of His ‘Movie’ Career,” in Mia Mask, ed. Contemporary Black American Cinema: Race, Gender and Sexuality at the Movies (New York: Routledge, 2012), 14-39. [an earlier version of this appeared in Cinemas 19:1 (2009), 147-179.]

Paul Robeson has somehow gotten under my skin. I owe this ongoing fascination to Rae Alexander Minter, who was director of the Paul Robeson Cultural Center at Rutgers University and organized a 1998-99 centennial exhibition that toured to several sites around the US. (Robeson was born in 1898.) Rae and I had worked together at the New-York Historical Society in the 1980s and we became pals. I ended up advising the film aspect of the centennial exhibition, which proved unexpected popular with funders. Along with Mark Reid and Ed Guerrero, we curated fim retrospectives at UCLA Film & Television Archives and at the Museum of Modern Art. As we divvied up the film notes, I proposed that we pick a card to decide who should get what. I lost–and received quite a bit of good nature ribbing as they stuck me with writing the about Tales of Manhattan (Jules Duvivier, 1942). That was the beginning of this particular essay, for the film––which came at a pivotal point in Robeson’s film career––unexpectedly interesting. It was made by a bunch of lefties; and if ever there was “Communist-inspired” dialogue in a Hollywood movie, it can be found in this one. But the film was criticized for its stereotypes, and Robeson threw it under the bus in order to protect his starring role in the stage version of Othello.

“Cinema, Newspapers and the U.S. Presidential Election of 1896,” in A. Quintana and J. Pons, eds., The Construction of News in Early Cinema (Girnoa, Spain: Museu del Cinema, 2012), 65-84.

“Cinema, Newspapers and the U.S. Presidential Election of 1896,” in A. Quintana and J. Pons, eds., The Construction of News in Early Cinema (Girnoa, Spain: Museu del Cinema, 2012), 65-84.

This comes out of a conference in Girona, Spain (or Girona, Catalonia). It was my first time in that country and a joyful experience. My presentation was on the media shift that occurred between the 1892 and the 1896 US presidential election–in short a foray into the area of my current book interest (admittedly a hazardous assertion). I am not just interested in the introduction of cinema into the world of politics only a few months after the debut of the Vitascope (ie projected motion pictures) in the United States, but in the overall media formation in which film functioned for campaign purposes. The collection is in three different languages and there are a few small problems with the text that often arise (for whatever reason) with foreign publications. Nevertheless, my essay offers new insights on a subject that I have written about in the past. One argument: Biograph’s program of films featuring McKinley at Home is not an example of cinema of attractions but montage of attractions, avant la lettre.

You’ll find it here: Cinema,Newspapers&USPresidentialElectionof1896

My essay “The Early Cinema of Edwin S. Porter” was reprinted with a specially written introduction. It appears in Cynthia Lucia, Roy Grundmann, and Art Simon, eds., The Wiley-Blackwell History of American Film, vol. 1 (Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012), 39-86.

I am delighted to finally have this article anthologized––just in time for its 35th anniversary! (It won the SCS -now SCMS- Student Award for Scholarly Writing in 1978 and was initially published in Cinema Journal, 19: 1 (1979), 1-38. In many ways, it was my breakthrough into academic scholarship. In my new introduction, I wrote:

It might seem an indulgence to have an essay reprinted that is now more than 30 years old, but “The Early Cinema of Edwin S. Porter” has the virtue of raising basic issues that remain part of the debates still swirling around cinema of the early 1900s. Not only does it stand up in most of its essentials, but this effort also retains a freshness (a sense of working through a problem for the first time) and urgency that would be difficult to resurrect. Nonetheless, some introductory comments might provide a useful commentary and historical context for this essay.

You’ll find the introduction and essay here: “The Early Cinema of Edwin S. Porter”.

My article “Why Did Negroes Love Al Jolson and The Jazz Singer?: Melodrama, Blackface and Cosmopolitan Theatrical Culture” recently appeared in Film History, 23:2 (2011) 198-222.

Mary Dale (Mae McVoy) and Jack Robin (Al Jolson) in The Jazz Singer

The article, Musser, JazzSinger, is first and foremost a response to Michael Rogin’s book Blackface, White Noise: Jewish Immigrants in the Hollywood Melting Pot (1996). I was and remain deeply impressed by Rogin’s assessment of Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation in his essay “‘The Sword Became a Flashing Vision’: D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation” in Representations, No. 9 (Winter, 1985), pp. 150-195. Like many other scholars of American culture, when teaching The Jazz Singer, I adopted his assessment of the film as a key work in the long trajectory of racism in American cinema. Subsequently, while conducting research on Oscar Micheaux in the African American Press in the 1920s, I occasionally encountered documents that suggested Jolson was well received in the African American community. This was in the later 1990s. Although I wanted to pursue this dissonant evidence, there were other more urgent projects and I generally prefer to write articles when I have more than one fresh perspective. Then when I saw E. A. Dupont’s masterful silent film The Ancient Law (1923) at the 2007 Giornate del Cinema Muto, I realized that it must have been a source for the Warner Brothers ‘ first feature-length “talkie.” I set to work, and my first presentation on the subject was at Emory University in April 2008, thanks to Matthew Bernstein and Karla Oeler. A closer look at the black press, made clear that Jolson was the most popular movie star among African Americans in the late 1920s. On more than one occasion, his use of black face was said to make Jolson the successor to Bert Williams! Jolson’s remarkable, Brechtian-like performance style on the stage in the mid-1920s as well as his promotion of black entertainers demand a more discerning and sympathetic treatment. Jolson might best be seen as an active participant in the Harlem or New Negro Renaissance which often functioned at the intersection of white patronage and black creativity. Anyway, I like this article: its only fault might be that it had to deal with many more issues than I had initially expected. It starts with a grateful nod to Linda Williams and her essay on body genres.

Charles Musser, “The Stereopticon and Cinema: Media Form or Platform?” French translation in François Albera and Maria Tortajada, eds. Ciné-dispositifs: spectacles, cinema, television, literature (Lausanne, Suisse: L’age de Homme, 2011) as “Le Stereopticon et le Cinema: Forme de Media Form or Plate-forme de Medias?” 133-168.

OK. If you are not fluent in French, you’ll have to wait for the English language edition. Here is the issue in brief: is cinema a media form? Or is it motion pictures, and projection in a theater just involves one of many platforms for motion pictures. The French think one thing and most in the Anglo-American world another–but we rarely examine what is at stake. I displace this historically because the same issues came up with the stereopticon in the 19th century. The question of Digital Cinema may force yet another engagement with this issue. In any case, this is my modest contribution to the emerging field of “platform studies.” However, I think we don’t even really agree on what constitutes a platform or where are the technological disjunctions.

Charles Musser, “Paul Robeson and the Cinema of Empire” in Lee Grieveson and Colin McCabe, eds. Empire andl Film (London: Palgrave, 2011), 261-280.

Charles Musser, “Paul Robeson and the Cinema of Empire” in Lee Grieveson and Colin McCabe, eds. Empire andl Film (London: Palgrave, 2011), 261-280.

I have been writing about Paul Robeson and his films ever since I became involved in the Paul Robeson centennial celebrations organized by Rae Alexander Minter in the mid 1990s, when she was running the Paul Robeson Cultural Center. I’ve written half a dozen published articles on his film work, and this will eventually become a book. My essay in this collection is based on a presentation I gave at the “Colonial Film: Moving Images of the British Empire” conference organized by Colin MacCabe and Lee Grieveson at Birkbeck College, London, UK from 7-9 July 2010. I knew this conference would provide an essential context to think about Robeson’s films of the 1935-38 period–films such as Sanders of the River (1935), King Solomon’s Mines (1937) and Jericho (1937). That conviction proved completely accurate. I also benefited from critical feedback from both Lee and Colin. Thanks to both of them and to the other participants.

Charles Musser, “Truth and Rhetoric in Michael Moore’s Fahrenheit 9/11,” in Mathew Bernstein, ed., Michael Moore: Filmmaker, Newsmaker, Cultural Icon (University of Michigan Press, 2010), 167-201. Michael Moore has been successfully demonized by the political right. They were much more successful in undermining the credibility of Fahrenheit 9/11 than the left was at challenging the SWIFT Boat ads against John Kerry. And arguably that was the key to the election. I admire Moore but I wanted to look at his documentary and the criticisms against it from a dispassionate view point. Many Bush supporters refused to see Fahrenheit 9/11 but I made a point of seeing the anti-Moore documentaries and judge their strengths and weakness. Was their outrage justified or did they play fast and loose with “the truth” in the midst of a heated electoral campaign?

Charles Musser, “Truth and Rhetoric in Michael Moore’s Fahrenheit 9/11,” in Mathew Bernstein, ed., Michael Moore: Filmmaker, Newsmaker, Cultural Icon (University of Michigan Press, 2010), 167-201. Michael Moore has been successfully demonized by the political right. They were much more successful in undermining the credibility of Fahrenheit 9/11 than the left was at challenging the SWIFT Boat ads against John Kerry. And arguably that was the key to the election. I admire Moore but I wanted to look at his documentary and the criticisms against it from a dispassionate view point. Many Bush supporters refused to see Fahrenheit 9/11 but I made a point of seeing the anti-Moore documentaries and judge their strengths and weakness. Was their outrage justified or did they play fast and loose with “the truth” in the midst of a heated electoral campaign?

Charles Musser, “Carl Marzani & Union Films: Making Left-wing Documentaries during the Cold War, 1946-53” The Moving Image, 9:1 (Spring 2009): 116-172. The Red Scare had a major impact on scholarship in many area. When dealing with the post-WW II era, Robert Flaherty’s Louisiana Story (1948) was routinely hailed as the high point of documentary achievement. Union Films–head by Carl Marzani–is never mentioned, even in histories of left-wing filmmaking. Union Films was probably the major producer of left-wing documentaries in the immediately post-war period–over two dozen between 1947 and 1954. They made a who series of campaign films for Henry Wallace (left) and Vito Marcantonio (center)––many of which featured Paul Robeson. In the process of research I got to know the families of both Carl Marzani (producer) and Max Glandbard (director). Here is the essay. Musser-MarzaniandUnionFilms

Charles Musser, “Carl Marzani & Union Films: Making Left-wing Documentaries during the Cold War, 1946-53” The Moving Image, 9:1 (Spring 2009): 116-172. The Red Scare had a major impact on scholarship in many area. When dealing with the post-WW II era, Robert Flaherty’s Louisiana Story (1948) was routinely hailed as the high point of documentary achievement. Union Films–head by Carl Marzani–is never mentioned, even in histories of left-wing filmmaking. Union Films was probably the major producer of left-wing documentaries in the immediately post-war period–over two dozen between 1947 and 1954. They made a who series of campaign films for Henry Wallace (left) and Vito Marcantonio (center)––many of which featured Paul Robeson. In the process of research I got to know the families of both Carl Marzani (producer) and Max Glandbard (director). Here is the essay. Musser-MarzaniandUnionFilms

***

![Sarah Bernhardt in New York City [December 1, 1912].](http://www.charlesmusser.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/SarahBernhardtNYC1912-208x300.jpg)

Dear Professor Musser,

What a breath of much needed fresh air your article on Jolson and “The Jazz Singer,” presents! After years and years of revisionist history concerning the true nature of Jolson and his relationship to the black community, his use of blackface, and the repeated accusations that Jolson’s obvious bigotry, you grace us with reason, logic and truth.

Your discussion of the possible precursors to, “The Jazz Singer,” is equally fascinating and the entire article should now be required reading in every curriculum of every theater or film degree program!

I look forward to more essays in this area, which is a largely unexplored one, by yourself and by anyone who wishes to shed light on this unique and remarkable period of American entertainment.

Bravo!

Joe Ciolino

NYC