I arranged for Judith Helfand to come to Yale and talk with students in my course on Documentary and the Environment. The week was devoted to her work: my lecture was followed by a showing of Blue Vinyl (2002)–with A Healthy Baby Girl (1997) as an optional extra for dedicated students, of which there were quite a few. She came for the discussion section and later that evening she screened Everything’s Cool (2007) at the School of Forestry and Environmental Studies. It was a great visit–inspiring for students while it gave me a chance to think more about her films and career trajectory.

I arranged for Judith Helfand to come to Yale and talk with students in my course on Documentary and the Environment. The week was devoted to her work: my lecture was followed by a showing of Blue Vinyl (2002)–with A Healthy Baby Girl (1997) as an optional extra for dedicated students, of which there were quite a few. She came for the discussion section and later that evening she screened Everything’s Cool (2007) at the School of Forestry and Environmental Studies. It was a great visit–inspiring for students while it gave me a chance to think more about her films and career trajectory.

Judith is, of course, a prominent member of the New York documentary community; and while we share an NYU connection, our paths failed to overlap for many years. This failure had become sufficiently ridiculous; and so I finally attended a screening of A Healthy Baby Girl at the Stranger Than Fiction series, where Judith did a post-screening Q & A. (The exact date was March 2, 2010.) We met again unexpectedly at the 2014 Big Sky Documentary Film Festival, where we managed to have a drink together at the hotel bar: I was there with Errol Morris: A Lightning Sketch, while she was on a panel of nonprofit funders and TV program commissioners who were overseeing a set of mock pitch sessions for filmmakers looking to fund their next projects. She gave such insightful and supportive feedback that I concluded that my students would benefit from her presence as well.

Judith is, of course, a prominent member of the New York documentary community; and while we share an NYU connection, our paths failed to overlap for many years. This failure had become sufficiently ridiculous; and so I finally attended a screening of A Healthy Baby Girl at the Stranger Than Fiction series, where Judith did a post-screening Q & A. (The exact date was March 2, 2010.) We met again unexpectedly at the 2014 Big Sky Documentary Film Festival, where we managed to have a drink together at the hotel bar: I was there with Errol Morris: A Lightning Sketch, while she was on a panel of nonprofit funders and TV program commissioners who were overseeing a set of mock pitch sessions for filmmakers looking to fund their next projects. She gave such insightful and supportive feedback that I concluded that my students would benefit from her presence as well.

Judith Helfand having lunch with three students from Documentary and the Environment: Samantha Lichtin, Ila Tyagi, and Tasnim Elboute

Judith has consistently focused her powerful documentaries on environmental issues, beginning even with Uprising of ’34 (1995), which she co-directed with George Stoney. As a DES daughter who suffered life transforming cervical cancer, she can speak with special authority on a range of environmental issues, but it is her personal openness, humor and political commitment that utilizes that experiential gravitas to make her remarkable films.

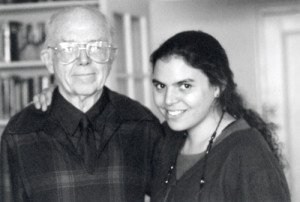

Both Judith and I owe a debt to George Stoney, and I have always been curious why we did not intersect much sooner. Judith took George’s documentary filmmaking class in the spring of 1985, then left NYU to work in the New York world of professional documentary production––just as I was leaving it. After I finished my Ph.D. from NYU in the fall of 1986; George Stoney generously allowed me to teach his two-semester Documentary History course in 1987-88 and 1988-89 while he pursued other projects. It was my first lecture course and the first time I taught documentary. ( I was and will always be grateful to George but truth be told, we did not have much interaction.) In April 1990, faced with a radical hysterectomy at age 25, Judith called George–who offered her a job post-surgery. By the time Judith was working with George, I had left NYU behind and was completing my books on American early cinema. She finally completed her course work and received BFA from NYU in 1994. By then I was program building at Yale. We were ships passing in the night.

Both Judith and I owe a debt to George Stoney, and I have always been curious why we did not intersect much sooner. Judith took George’s documentary filmmaking class in the spring of 1985, then left NYU to work in the New York world of professional documentary production––just as I was leaving it. After I finished my Ph.D. from NYU in the fall of 1986; George Stoney generously allowed me to teach his two-semester Documentary History course in 1987-88 and 1988-89 while he pursued other projects. It was my first lecture course and the first time I taught documentary. ( I was and will always be grateful to George but truth be told, we did not have much interaction.) In April 1990, faced with a radical hysterectomy at age 25, Judith called George–who offered her a job post-surgery. By the time Judith was working with George, I had left NYU behind and was completing my books on American early cinema. She finally completed her course work and received BFA from NYU in 1994. By then I was program building at Yale. We were ships passing in the night.

As I explored Judith’s work, I found myself thinking about documentary partnerships–filmmaking collaborations. I have relied on them myself with mixed success. Much of Errol Morris: A Lightning Sketch depended on a productive collaboration with Carina Tatu, who shot the film and did most of the preliminary editing. Our later efforts were perhaps not so successful, and for various reasons we went separate ways. Currently I am collaborating on a documentary project–Visa Wives––with my wife Threese Serana. And of course there are many collaborative pairs: the Maysles Brothers, Pennebaker-Hegedus, Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky. The list goes on. In any case, Judith has tended to work collaboratively and I was interested in the results. The Uprising of ’34 was George Stoney’s film–his idea and his subject. He initially hired her as an associate producer, but her contributions were such that she became to co-director. She was, one can say, the perfect collaborator in this situation.

While working with George, she was also making A Healthy Baby Girl. For this she had no filmmaking partner though certainly she had supportive associates. There is a scene in the film where she is filming herself sitting on a bed and talking to the camera–strongly reminiscent of Ross McElwee’s Sherman’s March (1986). Our class had already seen several documentaries in which the filmmaker is also the protagonist of the film––Gasland, DamNation, Super Size Me––and of course there are many other documentaries in this period where the filmmaker leads us through the film (e.g. any documentary by Michael Moore and many others by Nick Broomfield). The female filmmaker as protagonist is a rarer phenomenon. Judith and Agnes Varda are the two featured in the course. (I asked Judith about her familiarity with such feminist documentaries of the 1970s as Joyce at 34 [1972] and Nana, Mom and Me [1974]: she had not seen them.) It was on A Healthy Baby Girl, which won a Peabody Award, that Judith hired Daniel Gold as a cameraman. (One thing that was cleared up for me by her visit: her boyfriend Daniel in the film and cinematographer Daniel Gold are two different people.)

Daniel Gold became Judith’s collaborator on her next film: Blue Vinyl, an impressive, wonderful film that my students have been writing about it in their mid-term papers.