Let me begin this post by expressing my deepest thanks to the organizers of the Pordenone Silent Film Festival–the Giornate del Cinema Muto: David Robinson, Livio Jacob, Piera Patat and Paolo Cherchi Usai among many others. Each year we are blessed to be humble participants in this, your most remarkable, annual achievement. You have legions of fans. I am one.

I am starting to write this post from the Giornate del Cinema Muto in Pordenone, Italy, where I make my annual October pilgrimage for a one week submersion in silent film––one of the two principal areas in my academic portfolio. It keeps me up-to-date in all sorts of important ways. Screenings start at 9 am (sometimes 8:30) and generally run until midnight or soon thereafter. We are here for the films but also to see friends and colleagues from all over the world. Business seems to get done as well–perhaps more about that later. This perfect mix always reminds me (and I think everyone else who’s here) of the reasons why we got into this field. But just to be clear: sitting in a darkened theater for 12 hours a day involves discipline and even training: it is not everyone’s cup of tea. Film festivals invert the relationship between the movie world and the real world. Jet lag makes it even more of a challenge (it is almost impossible to reset your biological clock when in darkness most of the day), but for some reason red wine at meal time helps. It’s a tough job but someone has to do it.

I am starting to write this post from the Giornate del Cinema Muto in Pordenone, Italy, where I make my annual October pilgrimage for a one week submersion in silent film––one of the two principal areas in my academic portfolio. It keeps me up-to-date in all sorts of important ways. Screenings start at 9 am (sometimes 8:30) and generally run until midnight or soon thereafter. We are here for the films but also to see friends and colleagues from all over the world. Business seems to get done as well–perhaps more about that later. This perfect mix always reminds me (and I think everyone else who’s here) of the reasons why we got into this field. But just to be clear: sitting in a darkened theater for 12 hours a day involves discipline and even training: it is not everyone’s cup of tea. Film festivals invert the relationship between the movie world and the real world. Jet lag makes it even more of a challenge (it is almost impossible to reset your biological clock when in darkness most of the day), but for some reason red wine at meal time helps. It’s a tough job but someone has to do it.

Once again the organizers offered a remarkable program with several strands of material. Speaking personally (a confession?), the festival is often serving a remedial purpose. This quickly became clear on Sunday evening, October 5th, with the screening of Fred Niblo’s Ben Hur (1925). Though the film often indulges in false sentimentality (religious and otherwise), the chariot scene was extraordinary. To be sure, numerous horses (and apparently at least one stuntman) died during the shooting of this scene. The only way to make this picture today would be through digital effects. The spectacle is impressive and it seems that Ramon Novarro, who played Ben Hur, combined remarkable sex appeal with more than decent ability as a film actor. His is another tragic story of a closeted gay star, and this film is poignant testimony to his remarkable talent.

Once again the organizers offered a remarkable program with several strands of material. Speaking personally (a confession?), the festival is often serving a remedial purpose. This quickly became clear on Sunday evening, October 5th, with the screening of Fred Niblo’s Ben Hur (1925). Though the film often indulges in false sentimentality (religious and otherwise), the chariot scene was extraordinary. To be sure, numerous horses (and apparently at least one stuntman) died during the shooting of this scene. The only way to make this picture today would be through digital effects. The spectacle is impressive and it seems that Ramon Novarro, who played Ben Hur, combined remarkable sex appeal with more than decent ability as a film actor. His is another tragic story of a closeted gay star, and this film is poignant testimony to his remarkable talent.

Another long-standing gap is my viewing was filled by the screening of Fritz Lang’s Die Nibelungen (Part 1: Siegfried and Part 2: Kriemhild’s Revenge). Again this shows why the Giornate is so important.

Princess Kriemhild accuses her brother, King Gunther, of killing her husband Siegfried who is also Gunther’s blood brother. She’s right.

Die Nibelungen is not the kind of film that should be seen on a computer or TV screen. It must have suffered many small deaths when shown in old-fashioned projection rooms with a 16mm print. To see this film, one needs an occasion: a free evening, a beautiful 35mm print, a small orchestra, and a full theater.

It is often noted that Lang’s picture was one of Hitler’s favorites. If so, it is hardly surprising that Hitler failed to understand what might be seen as the film’s lesson–its warning. The Germanic Nibelungens wreck havoc on a smaller and darker race, but this violence ultimately produces an orgy of self-destruction in which the

surviving Nibelungens retreat into a bunker and die in a malestrom of fire. This was to be Hitler’s fate as well. Of course, such an interpretation looks at the film in light of future events, rather seeing it as an allegory about the traumas of World War I, as Anton Kaes does in his book Shell Shock Cinema. In fact, Tony and I discussed this very topic over lunch–standing Kracauer’s From Caligari to Hitler: A Psychological History of the German Film on its head. Unfortunately Tony had to leave before the Lang epic was screened, so I missed the post-screening dissection.

surviving Nibelungens retreat into a bunker and die in a malestrom of fire. This was to be Hitler’s fate as well. Of course, such an interpretation looks at the film in light of future events, rather seeing it as an allegory about the traumas of World War I, as Anton Kaes does in his book Shell Shock Cinema. In fact, Tony and I discussed this very topic over lunch–standing Kracauer’s From Caligari to Hitler: A Psychological History of the German Film on its head. Unfortunately Tony had to leave before the Lang epic was screened, so I missed the post-screening dissection.

One major strand of the festival offered films by the Barrymore clan. I am continually fascinated by John Barrymore and his fluid move between theater and film in the 1910s and early 1920s. So it was good to see a nice 35mm print of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1920). Yale has 16mm prints of this and other Barrymore vehicles such as Beau Brummel and The Beloved Rogue (1927), but seeing them in 35mm on a big screen was an entirely new experience, particularly Jekyll and Hyde. Likewise, I had never seen When a Man Loves (1927), a Warner Brothers film with a Vitaphone sound track, made in the immediate wake of Don Juan (1926). One of the things that is so compelling about Barrymore’s film performance is his sense of fun. He doesn’t take any of it too seriously and is always ready to be outrageous. The screwball actor of Howard Hawks 20th Century (1934), in which JB plays Oscar Jaffe, was already present in the 1920s.

In contrast, I knew very little about other Barrymore family members in this period, notably JB’s sister Ethel and brother Lionel. Often guilty of genealogical ignorance, I learned (or perhaps was reminded) that the delightful film comic Sidney Drew was their uncle. To bring this to the present day, it is hard not to notice that Drew Barrymore looks a lot like her great aunt Ethel. The source of her first name is worth noting as well. (Sometimes I am a little slow about these things.)

In The White Raven (1917) Ethel Barrymore plays Nan Baldwin, the daughter of a failed stock broker, who seeks refuge in Alaska gold fields where she sings for a living. Belle of the saloon, she gets offers of marriage but feels trapped. To escape, she sells her self–payment deferred–for funds so she can travel to New York and train as a opera singer. Soon the winner of the competition (William B. Davidson) leaves the gold fields for New York. He meets the newly triumphant Nan, who fails to recognize him without his beard and change of manner. They fall in love, but she refuses his offer of marriage and returns to Alaska and the man who bought her. All turns out happily, of course. As with so many of these Barrymore films, the plots are contrived melodramas and the camerawork is competent but predictable. Other actors are fine but forgettable. What one has is a star vehicle in which Ethel B offers a restrained, effective performance.

In The White Raven (1917) Ethel Barrymore plays Nan Baldwin, the daughter of a failed stock broker, who seeks refuge in Alaska gold fields where she sings for a living. Belle of the saloon, she gets offers of marriage but feels trapped. To escape, she sells her self–payment deferred–for funds so she can travel to New York and train as a opera singer. Soon the winner of the competition (William B. Davidson) leaves the gold fields for New York. He meets the newly triumphant Nan, who fails to recognize him without his beard and change of manner. They fall in love, but she refuses his offer of marriage and returns to Alaska and the man who bought her. All turns out happily, of course. As with so many of these Barrymore films, the plots are contrived melodramas and the camerawork is competent but predictable. Other actors are fine but forgettable. What one has is a star vehicle in which Ethel B offers a restrained, effective performance.

Despite his appearance in some Griffith/Biograph films, my enduring memory of Lionel Barrymore is the wheelchair-bound senior in Key Largo (1948). The Giornate unveiled the early Lionel Barrymore in The Strong Man’s Burden (Biograph, 1913), in which he plays an honorable policeman whose brother (Harry Carey) is a dishonorable thief. Inevitably their paths cross and the policeman (Barrymore) allows his brother to escape, then shoots himself both to cover up his dereliction of duty and to serve as a kind of (self) punishment. The complexity and tension of this melodramatic situation easily allows for a bravura even excessive performance, but Lionel B is so restrained that the character’s psychological agonies are almost effaced.

Restraint but not effacement characterize his powerful performances in The Copperhead (1916) and Jim the Penman (1921). In both films, his character has to operate in highly constrained circumstances in which he must conceal his true feelings. In the earlier film, LB’s character, Milt Shanks, poses as a Southern sympathizer during the Civil War (at the personal behest of Abraham Lincoln, no less), using that position to pass on information that the Union army can use against the Confederates. His wife and son are angered and dismayed by his apparent choices. Inevitably his outward persona and inward feelings are at war with each other; and in fact they are forced to remain this way long after the war ends. Finally he is shot by a Southern sympathizer he seemingly befriended but actually betrayed. Only as he lays dying is this ardent Unionist able to drop his tortuous mask, making death its own kind of release.

In Jim the Penman, James Ralston (Lionel B) loves the daughter of his employer, a banker whose get rich schemes puts him on the edge of bankruptcy. Against his better judgment, Ralston forges a check and is quickly entrapped by a criminal organization for which he must work, against his will (though also with mixed emotions as he prospers personally). Again this tension between calm public persona and internal psychic torture facilitates a retrained but intense acting style, which finally explodes in the final reel as Ralston sends the criminal gang–and himself–to the bottom of the sea, trapped inside a sinking boat.

The Bells (1926), directed by James Young, is set in Eastern Europe during the 19th century. The film serves as another vehicle for Lionel Barrymore who gives a tour de force performance as Mathias, a tavern owner and small time businessman who is too easy going and too generous with his money. Even as his finances spin out of control, he strives to become the local mayor by dispensing drinks and other gifts he can ill afford. Opportunistically, he solves his financial problems by murdering a Jewish pedlar, taking his money belt of gold, and then disposing of his body in a lime kiln. Although he may enjoy the respect of his fellow townspeople and his daughter finds happiness in a desirable marriage, Mathias is tortured by guilt and the threat of discovery. The pedlar’s brother arrives and seeks the murderer, offering a large reward. A clairvoyant (Boris Karloff) hovers, ready to read his mind. Mathias unravels over the course of the film as his hallucinations and dreams become more and more overwhelming. It reminds me of Charles Gilpin’s performance in Ten Nights in a Barroom (Colored Players of Philadelphia, 1926)–the same year.

The most outrageous member of the Barrymore clan was Sidney Drew. His short Goodness Gracious: Or the Movies as They Shouldn’t Be (1913) with Clara Kimball Young has been available through the Museum of Modern Art Circulating Collection for years—but always in 16mm. One can never see this film too many times and it was a treat to see it in 35mm. So much for narrative logic.

The most outrageous member of the Barrymore clan was Sidney Drew. His short Goodness Gracious: Or the Movies as They Shouldn’t Be (1913) with Clara Kimball Young has been available through the Museum of Modern Art Circulating Collection for years—but always in 16mm. One can never see this film too many times and it was a treat to see it in 35mm. So much for narrative logic.

At the very beginning of the Giornate, they screened a number of comedies featuring Mr. and Mrs. Sidney Drew. Most were from the Library of Congress, which is a good thing since I arrived part way through the screening in a jet lag daze.  Her Anniversaries (1917) was pretty hilarious as the wife has a long list of anniversaries, which her husband fails to remember to her great pain and his sorrowful regret. Having once been married to a woman whose calendar was filled with anniversaries of a somewhat different kind–usually involving deaths––I could not fail to identify with the husband’s impossible task–since I too tend to be oblivious. The Drews were a lovely team with perfect comic timing. This is where Sidney D was like John B: both seem to be having a tremendous amount of fun doing what they were doing in front of the camera. Beyond these random observations, both Clara Kimball Young and Mrs. Sidney Drew (Lucile McVey) should be kept in mind for my imagined book A Feminist Moment in the Arts, 1910-1913.

Her Anniversaries (1917) was pretty hilarious as the wife has a long list of anniversaries, which her husband fails to remember to her great pain and his sorrowful regret. Having once been married to a woman whose calendar was filled with anniversaries of a somewhat different kind–usually involving deaths––I could not fail to identify with the husband’s impossible task–since I too tend to be oblivious. The Drews were a lovely team with perfect comic timing. This is where Sidney D was like John B: both seem to be having a tremendous amount of fun doing what they were doing in front of the camera. Beyond these random observations, both Clara Kimball Young and Mrs. Sidney Drew (Lucile McVey) should be kept in mind for my imagined book A Feminist Moment in the Arts, 1910-1913.

The Giornate also allowed us to compare three 1920s leading male stars of the swashbuckling, adventure-historical romance genre: Navarro, John Barrymore and Douglas Fairbanks.

We were able to see Fairbanks in action in one of his earlier films: the comic western The Good Bad Man (1915, a re-released version from 1923), directed by Allan Dwan, written by Fairbanks and shot by Victor Fleming. “Passin’ Through” (Fairbanks) conducts a slew of hold-ups for the sheer joy of it: holding up a train, he takes the conductor’s ticket punch, etc. The film turns serious when romance enters as “Passin’ Through” (Fairbanks) meets Amy (Bessie Love). Meanwhile the bandit king––Bud Frazier/the Wolf (Sam De Grasse)–wants Amy for himself and then it turns out that Bud Frazier had also killed the father of “Passin’ Through” when he was young–creating a parallel between the character and Fairbanks, whose father disappeared when he was five. The melodrama ends in the usual fashion. Not without charm (as William K. Everson might say), the film offers elements that would be reworked more memorably in slightly later films such as Wild and Woolly (1916). It also invites comparison with John Barrymore in The Incorrigible Dukane (1915), another film set in the west in which the ne’er-do-well son (JB) saves his father professional reputation and the dam he is building.

We were able to see Fairbanks in action in one of his earlier films: the comic western The Good Bad Man (1915, a re-released version from 1923), directed by Allan Dwan, written by Fairbanks and shot by Victor Fleming. “Passin’ Through” (Fairbanks) conducts a slew of hold-ups for the sheer joy of it: holding up a train, he takes the conductor’s ticket punch, etc. The film turns serious when romance enters as “Passin’ Through” (Fairbanks) meets Amy (Bessie Love). Meanwhile the bandit king––Bud Frazier/the Wolf (Sam De Grasse)–wants Amy for himself and then it turns out that Bud Frazier had also killed the father of “Passin’ Through” when he was young–creating a parallel between the character and Fairbanks, whose father disappeared when he was five. The melodrama ends in the usual fashion. Not without charm (as William K. Everson might say), the film offers elements that would be reworked more memorably in slightly later films such as Wild and Woolly (1916). It also invites comparison with John Barrymore in The Incorrigible Dukane (1915), another film set in the west in which the ne’er-do-well son (JB) saves his father professional reputation and the dam he is building.

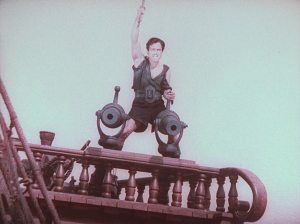

It is the Fairbanks of The Black Pirate (1926) that surprised me the most. The film was shown in lovely two-strip technicolor (the reason for its screening as part of a technicolor strand to the festival), but as I walked out of the theater I found its underlying ideology completely reactionary. Fairbanks is a duke who becomes a pirate king only to outwit –and out fight–the evil band of lowly plebeians. He does so in large part to rescue the helpless princess (Billie Dove), whom he is posed to marry at film’s end. Is there any way, to rescue this film’s horribly class-ist assumptions? Perhaps. We might consider Dove to be a Pickford stand-in at a time when Fairbanks and Pickford were cast in the role of Hollywood royalty. Color can be seen to reduce this film to a fantasy world that references nothing more than Hollywood itself. Certainly Fairbanks does his acrobatics and plays his role with swashbuckling gusto. As an aside, the high point of this Fairbanks films is when a boat-load of men dressed in leather (looking like frequenters of some gay bar of the 1980s) row a galley to the rescue (reminding us of Ben Hur). I was not unhappy to find myself immersed in the swashbuckling genre of the mid 1920s. Sophisticated, self-knowing and perhaps nodding to World War I but from an US perspective in which Americans could think of themselves as saviors (what do you think Tony Kaes?). But the economic inequalities it celebrates (Ben Hur is a prince, while JB plays a chevalier in When a Man Loves) anticipate the Depression and breadlines of the 1930s when examined from a Kracauerian POV). In any case one might compare The Black Pirate to a film in the genre from the next decade–Errol Flynn in Captain Blood (1937). And Pirates of the Caribbean with Johnny Depp evokes the Fairbanks vehicle in ways that are disquieting.

It is the Fairbanks of The Black Pirate (1926) that surprised me the most. The film was shown in lovely two-strip technicolor (the reason for its screening as part of a technicolor strand to the festival), but as I walked out of the theater I found its underlying ideology completely reactionary. Fairbanks is a duke who becomes a pirate king only to outwit –and out fight–the evil band of lowly plebeians. He does so in large part to rescue the helpless princess (Billie Dove), whom he is posed to marry at film’s end. Is there any way, to rescue this film’s horribly class-ist assumptions? Perhaps. We might consider Dove to be a Pickford stand-in at a time when Fairbanks and Pickford were cast in the role of Hollywood royalty. Color can be seen to reduce this film to a fantasy world that references nothing more than Hollywood itself. Certainly Fairbanks does his acrobatics and plays his role with swashbuckling gusto. As an aside, the high point of this Fairbanks films is when a boat-load of men dressed in leather (looking like frequenters of some gay bar of the 1980s) row a galley to the rescue (reminding us of Ben Hur). I was not unhappy to find myself immersed in the swashbuckling genre of the mid 1920s. Sophisticated, self-knowing and perhaps nodding to World War I but from an US perspective in which Americans could think of themselves as saviors (what do you think Tony Kaes?). But the economic inequalities it celebrates (Ben Hur is a prince, while JB plays a chevalier in When a Man Loves) anticipate the Depression and breadlines of the 1930s when examined from a Kracauerian POV). In any case one might compare The Black Pirate to a film in the genre from the next decade–Errol Flynn in Captain Blood (1937). And Pirates of the Caribbean with Johnny Depp evokes the Fairbanks vehicle in ways that are disquieting.

The festival is not just about films. A number of new books were having their festival debut. Laura Horak, a former Yale Film Studies major who subsequently received her Ph.D. at UC-Berkeley and is now teaching at Carleton University, had a book that was distributed to festival donors: Silent Cinema and the Politics of Space (edited by Jennifer M. Bean, Anupama Kapse, and Laura Horak). Laura was at the Giornate with her husband Gunnar Iversen. Knowing my devotion to the beginnings of cinema and my article on The John C. Rice-May Irwn Kiss, they spontaneously staged a re-enactment for my camera during a brief break between films:

The festival is not just about films. A number of new books were having their festival debut. Laura Horak, a former Yale Film Studies major who subsequently received her Ph.D. at UC-Berkeley and is now teaching at Carleton University, had a book that was distributed to festival donors: Silent Cinema and the Politics of Space (edited by Jennifer M. Bean, Anupama Kapse, and Laura Horak). Laura was at the Giornate with her husband Gunnar Iversen. Knowing my devotion to the beginnings of cinema and my article on The John C. Rice-May Irwn Kiss, they spontaneously staged a re-enactment for my camera during a brief break between films:

This confirms something we know well: scholars of early cinema have a strong appreciation for inter-textuality as well as a wonderful sense of humor!

John Fullerton, who teaches at Stockholm University and is responsible for my first visit to Sweden, was at the festival with his wife Elaine.

John and Elaine are festival regulars, but this year they had something special to celebrate: the publication of his book: Picturing Mexico: From the Camera Lucida to Film. Over lunch, I got John to inscribe my copy.

Picturing Mexico is published by John Libbey, one of early cinema’s secret weapons when it comes to publications (his imprint is distributed in the US by Indiana University Press). I wrote the introduction to another recent John Libbey publication, Before the Movies: American Magic Lantern Entertainment and the Nation’s First Great Screen Artist, Joseph Boggs Beale by Terry Borton and Deborah Borton. John Libbey held a Pordenone book party, which the Bortons did not attend. Nevertheless, all three authors of American Cinematographers in the Great War, 1914-1918 were there: James W. Castellan, Ron van Dopperen, and Cooper C. Graham.

Picturing Mexico is published by John Libbey, one of early cinema’s secret weapons when it comes to publications (his imprint is distributed in the US by Indiana University Press). I wrote the introduction to another recent John Libbey publication, Before the Movies: American Magic Lantern Entertainment and the Nation’s First Great Screen Artist, Joseph Boggs Beale by Terry Borton and Deborah Borton. John Libbey held a Pordenone book party, which the Bortons did not attend. Nevertheless, all three authors of American Cinematographers in the Great War, 1914-1918 were there: James W. Castellan, Ron van Dopperen, and Cooper C. Graham.

John Libbey received numerous thanks. I happily toasted him with his own wine while Professor Vanessa Toulmin provided John with a properly chaste imitation of May Irwin’s osculation–one completely in keeping with her new role as Head of Engagement at University of Sheffield.

The Giornate is not all celebrations and kisses. It is no secret that business gets done at this event. Archivists attend the festival so they can hold highly confidential meetings to determine the fate of silent cinema and future restorations. Bryony Dixon of the BFI and Mike Mashon of the Library of Congress met momentarily on the street, no doubt setting up just such a power coffee.

The Giornate is not all celebrations and kisses. It is no secret that business gets done at this event. Archivists attend the festival so they can hold highly confidential meetings to determine the fate of silent cinema and future restorations. Bryony Dixon of the BFI and Mike Mashon of the Library of Congress met momentarily on the street, no doubt setting up just such a power coffee.

Later that day independent film scholar Stephen Bottomore and David Francis met to talk about the imminent opening the new Kent Museum of the Moving Image, which David has created with his wife “Professor” Joss Marsh.

What about my own projects you might ask. Well, two of my current projects definitely received a boost.

I had a power lunch with Mike Mashon, and before I could bring it up, he was talking about the various films made by Carl Marzani and Union Films in the LOC collection. He was eager to get them out into the world and wondered if I was still interested in Union Films. Still interested! My suggestion of lunch had ulterior motives; and even as he raised this question, I had been trying to figure a way to discretely introduce Union Films into our conversation. The Union Films Project (core members: Dan Streible and the Orphan Film Symposium, Walter Forsberg and the Smithsonian, along with myself and the Yale Film Archive) has just added a new member. Yes!

I had a power lunch with Mike Mashon, and before I could bring it up, he was talking about the various films made by Carl Marzani and Union Films in the LOC collection. He was eager to get them out into the world and wondered if I was still interested in Union Films. Still interested! My suggestion of lunch had ulterior motives; and even as he raised this question, I had been trying to figure a way to discretely introduce Union Films into our conversation. The Union Films Project (core members: Dan Streible and the Orphan Film Symposium, Walter Forsberg and the Smithsonian, along with myself and the Yale Film Archive) has just added a new member. Yes!

The boost to a second project was much more unexpected. The Giornate was showing Toll of the Sea (1922) in its two-strip Technicolor strand. The picture’s place in film history is assured as the first technicolor feature. I had seen it more than once, though not, as it turned out, since I met my wife Threese Serana who is from the Philippines. I thought I would watch the first few minutes before heading out to grab a coffee. Instead I stayed, riveted by this movie that speaks so directly to the many stereotypes that we have encountered––from family as well as strangers. It is these stereotypes that compelled us to start work on our documentary with the working title Visa Wives, about the many women from the Philippines who come to the United States on K-1 or fiancée visas.

Toll of the Sea will somehow find its way into our film. Moreover, it was interesting to see that Technicolor was used for two other films of Asia exotica: The Love Charm (1928) and Manchu Love (1929). In The Love Charm, the captain of a yacht that is sailing the South Seas, glimpses a group of Polynesian women through his telescope and is immediately smitten. Upon reaching the island, he falls for a particularly alluring dancer, who fortunately turns out to be the daughter of a Western trader, who had gone native. Her white blood, of course, solves all the awkward problems of interracial romance. He can apparently have his cake and eat it, too. She can, likewise, fulfill all rescue fantasies.

In The Love Charm, the captain of a yacht that is sailing the South Seas, glimpses a group of Polynesian women through his telescope and is immediately smitten. Upon reaching the island, he falls for a particularly alluring dancer, who fortunately turns out to be the daughter of a Western trader, who had gone native. Her white blood, of course, solves all the awkward problems of interracial romance. He can apparently have his cake and eat it, too. She can, likewise, fulfill all rescue fantasies.

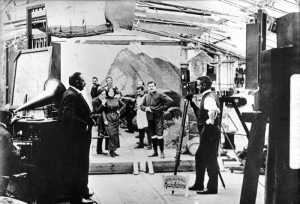

Another essential aspect of Pordenone screenings involves refining and perhaps correcting my earlier projects. In this regard the program of short films by Paul Nadar, made between 1896 and 1898, was particularly noteworthy–-and it matched one shown last year of films made for the Cinématographe Joly, which utilized a 35mm format but with five perforations, offering a more vertical image. It was its own distinct system–similar to, but incompatible with, the Edison and Lumiere projects. Nadar also had his own patented motion picture system, one which did not use sprocket film. It did not work very well so he also developed an Edison-compatible system. Nevertheless, this underscores the fact that there were numerous efforts to develop what we would now call non-standard systems. The Edison system marginalized most of these efforts–including Nadar’s––quite quickly. In this regard, Edison’s sale of kinetoscope films on an international basis and the appropriation of that format and technology by R.W. Paul, Birt Acres and others proved to be crucial.

Nadar’s films were of excellent quality. He took some street scenes but he also made dance films, including ones that featured Serpentine and Butterfly dancers. There is an early Serpentine film that is often attributed to Edison, but does not look as if it was shot in the Black Maria. I wonder if it is not Nadar’s. I have to find the still which is somewhere in my collection. What it would suggest–no surprise–is that Nadar’s films reached the US where they found a market.

Then there are moments like this one. Ana Grgic, a Ph.D. student at St. Andrews, had emailed me about a newspaper article that discusses Edison’s Blacksmith Scene (1893). Except the article, which is in Croatian, dates from November 1892. (It is likely a translation from an early article, possibly in German.)

Rather than correspond, I asked if Ana was coming to the Giornate. She was and so we met for a power coffee. What to make of this? Good question, but if the article is really about a blacksmith scene at the Edison Laboratory, our history of this period is going to need some refinement. At the very least it means the Blacksmith Scene was not shot in the Black Maria. Somewhat bewildered, I introduced Ana to Paul Spehr, whose book The Man Who Made Movies: W.K.L. Dickson (2008) is the latest word on this subject. In my excitement, I did not realize that Paul was about to go on stage and accept the Prix Jean Mitry for his outstanding life-long contribution to the study of early cinema.

One last example in this vein: the German Tonbilder films (sound films) made between 1907 and 1909. These films, including arias from Rigoletto and the opera Martha, were remarkable. They were one-shot films of three to four minutes, using techniques that have become standard for popular film musicals –lip syncing to pre-recorded music. The same kinds of films were also quite popular in the US at this time (the Cameraphone). The camera is always static and the films lack narrative. By the 10th film, my initial pleasure began to fade and that is what must have happened in Germany and the US by the later part of 1909. For more on these films see a blog by Antti Alanen.

One last example in this vein: the German Tonbilder films (sound films) made between 1907 and 1909. These films, including arias from Rigoletto and the opera Martha, were remarkable. They were one-shot films of three to four minutes, using techniques that have become standard for popular film musicals –lip syncing to pre-recorded music. The same kinds of films were also quite popular in the US at this time (the Cameraphone). The camera is always static and the films lack narrative. By the 10th film, my initial pleasure began to fade and that is what must have happened in Germany and the US by the later part of 1909. For more on these films see a blog by Antti Alanen.

One debate that may never end continues to revolve around the relationship between “cinema of attractions” and narrative film. Just to say that there were plenty of reminders that non-narrative attractions continued to appear in movie theaters with noteworthy regularity. These included such color shorts as Coloring the Stars: Number Four (1926) which showed a number of stars lounging at home, and Colorful Fashions from Paris (1926), a fashion show on film sponsored by McCall’s Magazine. Then there were the films that defied any narrative logic. They were not simply non-narrative (like the previous two), they were anti-narrative, specifically undoing, upending and refusing conventional Hollywood narratives. These include the previously mentioned Goodness Gracious (1913) with Sidney Drew and the Charlie Bower comedy Whoozit (1928). The following image is stolen from Antti Alanen blog. My thanks and apologies to him:

Of course there were more films, many more meals, and many late-night drinks that are not mentioned here. It is impossible to fully encompass the Giornate experience.

So here are some miscellaneous notes/highlights. Benshi Ichiro Kataoka came from Japan to accompany a group of Chaplin films, including Kid Auto Races at Venice (1914). Ichiro also gave a compelling lecture on the Benshi, translated from Japanese to English. Impressive.

So here are some miscellaneous notes/highlights. Benshi Ichiro Kataoka came from Japan to accompany a group of Chaplin films, including Kid Auto Races at Venice (1914). Ichiro also gave a compelling lecture on the Benshi, translated from Japanese to English. Impressive.

The Italian Association for Research on Cinema History celebrated its 50th anniversary. Founded in 1964, the only survivor from that occasion, Aldo Bernardini, took the stage to mark this occasion.

Meals with Andre Gaudreault, Vanessa Toulmin, Ian Christie, Chris Horak, Pat Loughney, Hiroshi Komatsu, Susan Ohmer and Don Crafton, Linda Williams, Diane and Richard Koszarski, Dana Benelli, Ansje van Beusekom, Paul Spehr, David Mayer, Karen and Russell Merritt.

On the left: Giornate fans who come with their own home-made T-shirts. If they contact me, I have a few more stills to give them. On the right, Market Day.

until next year…