The Yale Daily News published an abbreviated version of my statement about the Yale-NUS brouhaha in the run-up to this afternoon’s faculty meeting. It was a little bit of a tussle. Here is a fuller version of what I had originally written:

Yale-NUS and Yale-New Haven

We often tell ourselves that no email is really private; nevertheless, it was a surprise to discover that a small portion of an email I had sent to some of my colleagues about Yale-NUS was published in the Yale Daily News (“Yale takes brand to Singapore,” March 27th). These are informal exchanges, and not intended for public distribution. And what the YDN published was out of context.

Like some of my colleagues, I emailed President Levin and Provost Salovey six months ago to express my concerns about the Yale-NUS initiative—worried it would require significant in-kind time and energy. I was also worried about the known unknowns and the unknown unknowns—to paraphrase former Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld.

At this point the university as a whole is faced with a fait accompli. So far there have been no huge, unexpected challenges to the Yale-NUS effort, but it does seem to have become a distraction. Simply put, all is not well with the Yale-New Haven campus. Some of the best people—people we have worked with closely for years—left in the recent, abrupt reorganization of ITS. Shared Services is, from the perspective of many if not most faculty, a brutal and inappropriate effort to apply a corporate model to an academic institution. One thing Shauna King may not have realized is that tenured faculty cannot be fired the way staff can. Moreover, one hears numerous complaints about the kinds of directives and leadership coming out of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. Running Yale-New Haven is more than a full-time job, and one wonders if these problems––or some of them—would have been avoided if the top levels of the administration had kept their full attention closer to home.

It is important to remember that Rick Levin has been an outstanding president of Yale University. Anyone who remembers our pre-Levin university knows just how lucky we have been. (This is perhaps the main reason why it has taken so long for the faculty to shed their complacency in the face of a series of interlocking setbacks that cannot be simply linked to the budgetary crisis.)

Although Yale-NUS may be an unwanted distraction, it seems possible and finally important for faculty to engage President Levin’s efforts in a constructive and even supportive manner without, however, embracing them as our own. There is an unresolved conflict between Yale-NUS as an “autonomous” entity and its status as a Yale affiliate. The distinction is being fudged—and for what purpose and what end result is unclear, but likely this obscurity is purposeful. The faculty needs to take an active role in the future shaping of the Yale-NUS/Yale-New Haven relationship. This was the impetus for my email, which is offered here in a slightly refined version:

Colleagues–

I too find the use of the Yale name to be somewhat unnerving. If Yale-NUS is really an autonomous institution, Yale’s name should not be associated with it indefinitely. If it going to be something like a sister campus, the Yale name will remain and we (the faculty) need to be much more involved. What would we expect and find appropriate–and what would students and the world expect from a campus halfway around with the Yale name on it.

1) All students at Yale-NUS should be able to do a semester abroad at Yale-New Haven.

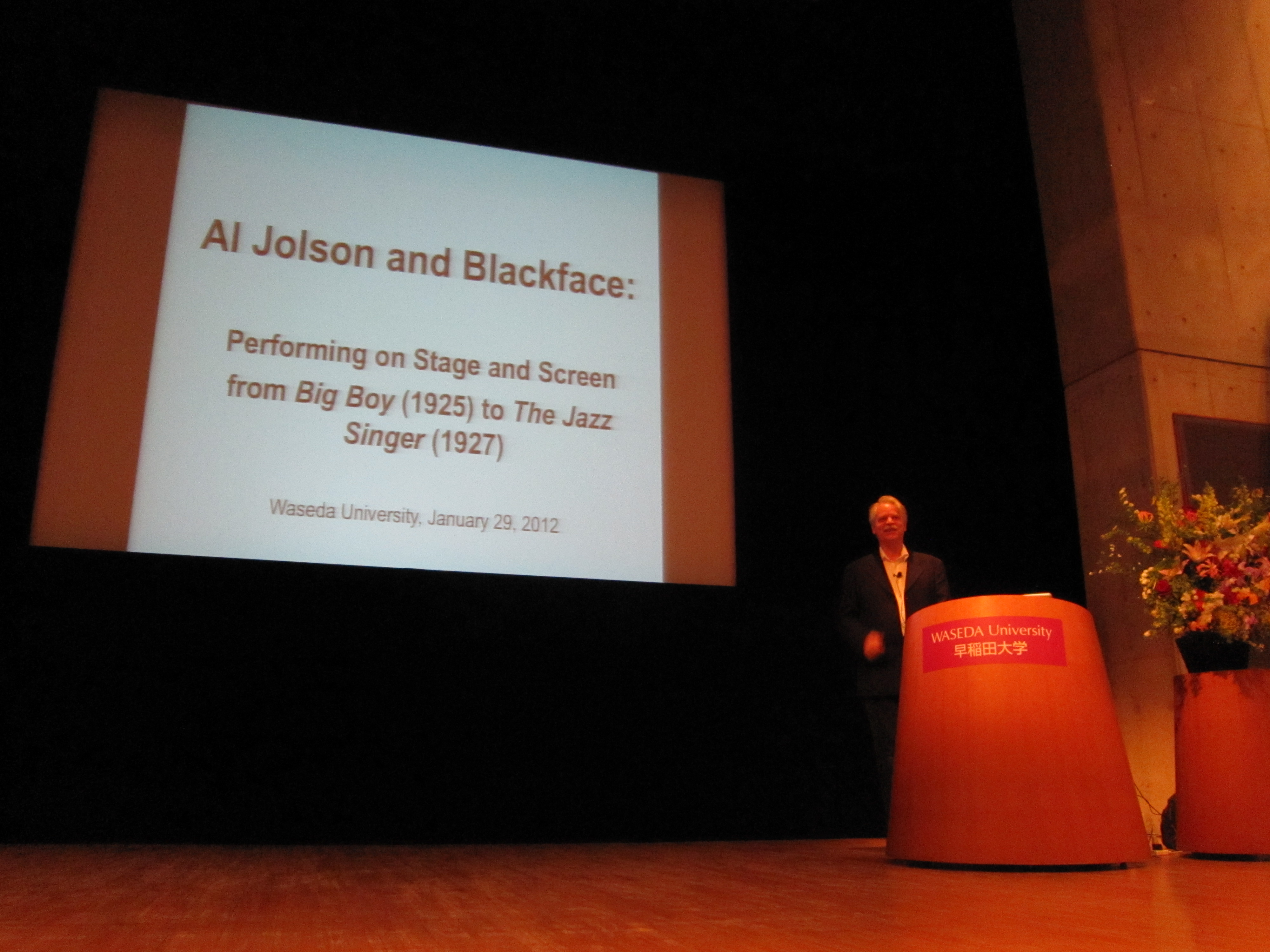

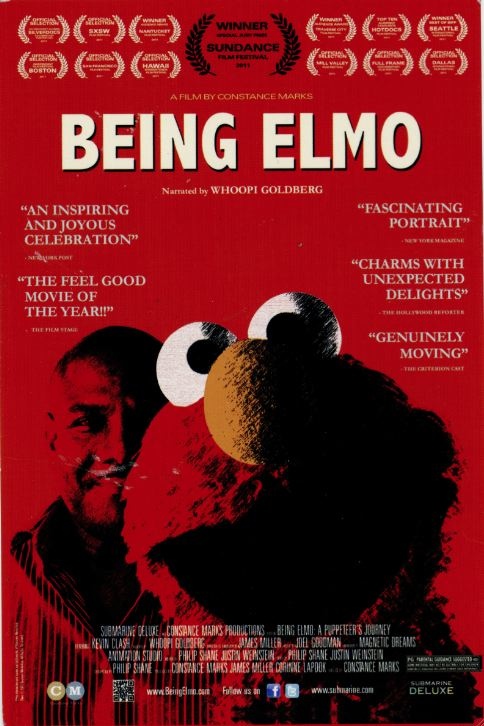

2) Yale-NUS students can come to Yale-New Haven to take our summer classes (not independent Yale-NUS summer classes). I think this is not bad. Frankly I have a lot of Film Studies faculty teaching in the Yale Summer Film Institute –and we may not get enough students for all their courses to run. Summer courses are also a way for our grad students to gain teaching experience.

3) We are already seeing that some 5th year MA students will come here for some “polishing.”

4) A certain number of transfer students each year seems inevitable and even appropriate.

5) Yale’s name on the degree itself.

Is Yale (or rather Yale-New Haven) going to be ready for that kind of substantial commitment? Are the faculty? The students? I have taught a number of NUS students in my summer courses and they have been very good––as good as the best students I have had during the school year. So one suspects that there would be no diminution in the quality of students.

I think we need 1) a forceful resolution like the one Seyla Benhabib proposed at the last faculty meeting and 2) another resolution calling for a future vote by the faculty–in 6 to 10 years whereby we will determine whether we believe a) Yale’s name should be on the BA degree that students receive at Yale-NUS or b) Yale be removed from the university’s name in a way that will signal its maturity as an independent institution.

At present, we are told that the Yale name can be taken off Yale-NUS if something goes wrong–-but what about if something goes right? What if Yale-NUS eventually became known as the Independent College of Singapore and was on its own? Or what if we discover that having a half-sister campus in Singapore is a boon? The assumption has been that we are generously bestowing our knowledge and educational wisdom on Singapore, but it seems more important (and more likely) that a truly successful outcome would result if our students and faculty members were learning from the dynamic exchanges generated by a properly reciprocal relationship. But is this what is envisioned? And is it what we want? How much would it change college life to have so many students rotating through? Who would not be attending Yale-New Haven if we are busy meeting our responsibilities to Yale-NUS?

These would be interesting questions to pursue if all was well at home. But across the university as well as in individual departments such as Film Studies (soon to be Film and Media Studies), faculty, staff and students continue to be affected by the endowment crisis, the top-down corporate model and long-standing problems that have continued to fester. It is true that the President and the Provost have re-engaged with the Yale faculty and we can not only hope but insist that this will be productive and not mere window dressing. Yale, to my mind, is a community––and not a corporation––dedicated to a rich and complex range of educational goals.

Charles Musser (BK ’73)

Professor of American Studies, Film Studies and Theater Studies