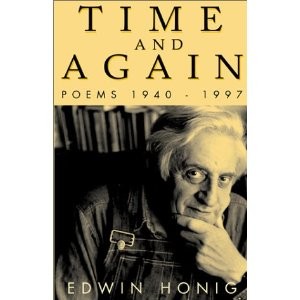

January 15th, 2013: Stranger Than Fiction at the IFC. Alan Berliner discusses his fabulous new film First Cousin Once Removed (2012). The cousin is Edwin Honig, a poet and translator who taught creative writing at Brown–an extraordinary, complicated man who could not forget one incredibly painful incident of his childhood (the death of his younger brother) –even as he is overwhelmed by dementia at the end of his life. It might, in fact, be the last memory he has until his memory is all gone. First Cousin is a film about memory and loss of memory, providing evidence that one can forget to the point that one never knew. A dense and complex film that I should watch more than once before writing too much. Alan offered a series of insightful comments and I only can hope that someone recorded them. At some point I just took out a pencil and scribbled down a few of his remarks. As he put it, “I have memory on the brain.” “Whatever the subject of my films, they contain layers and layers of subtext that are always about memory.” Despite Cousin Edwin’s frailties, Alan remarked that ” Everytime I met Edwin, it was a duet. He was in many ways the co-author of the film.”

First Cousin celebrates a man’s life and achievements by insisting on his complexities and flaws. Afterwards, Alan remarked that “poets are special citizens in our culture. They are beacons of truth as translator of experience, by making the invisible, visible.” It is a touching assertion that few Americans would stand by, but one that has a powerful credibility in the wake of First Cousin and its amazing excerpts of Honig’s poetry.

As Alan remarked, “Memory is not what happened but what you remember happened.” And, he confessed that when working on this film and other things, he has to write things down or he forgets. Me, too. And I realize that this blog is a record of things I would like not to forget–like this evening. In fact, those who occasionally encounter this blog may notice that it stopped for quite a few months. This happened because someone broke into our house and stole everyone’s still camera (that and jewelry, nothing else). With the loss of our camera–its own aid to memory, I stopped. And then when we bought a new one, I was out of practice and would forget to bring it with me. Although I brought it to Alan’s screening, I almost left it at home.

Anyway, here are a few more records of the evening. The theater was full but not with so many people that I knew. I still miss seeing George Stoney at these events. In fact, I thought a lot about George on this occasion. Someone at NYU finally told me what I had wanted to know. Faced with his failing eyesight and other physical ailments, George finally decided he had had enough and simply stopped eating. Two weeks later he was dead.

I also brought two students down from Yale. In a way, they stand in for the two sides of my teaching.

Eunju is making a documentary as her senior project on the people who live and work in the Yale library. So Alan’s documentary resonated. Should we be too surprised that he urged her to see Alain Resnais’ Toute la mémoire du monde (1956). Agreed. It was one of several documentaries she has seen on libraries in preparation for making her film. Josh is immersed in writing his dissertation “Los Angeles Documentary and the Production of Public History, 1958-1977,” a project in which he was often interviewing important figures in the last years (or months) of their lives. Of course, public history is also very much about public memory.

Alan’s film resonated with me in a very personal way in that I made a documentary about an inspirational figure and surrogate father in my life, the studio potter Gerry Williams. I made An American Potter more than 35 years ago but we have, of course, remained close. Gerry has also been struggling with Alzheimer’s disease and was moved to a nursing facility since I last saw him. There is a scene in Alan’s documentary when he brings his son to visit Honig. I had already brought John Carlos to visit Gerry as well.