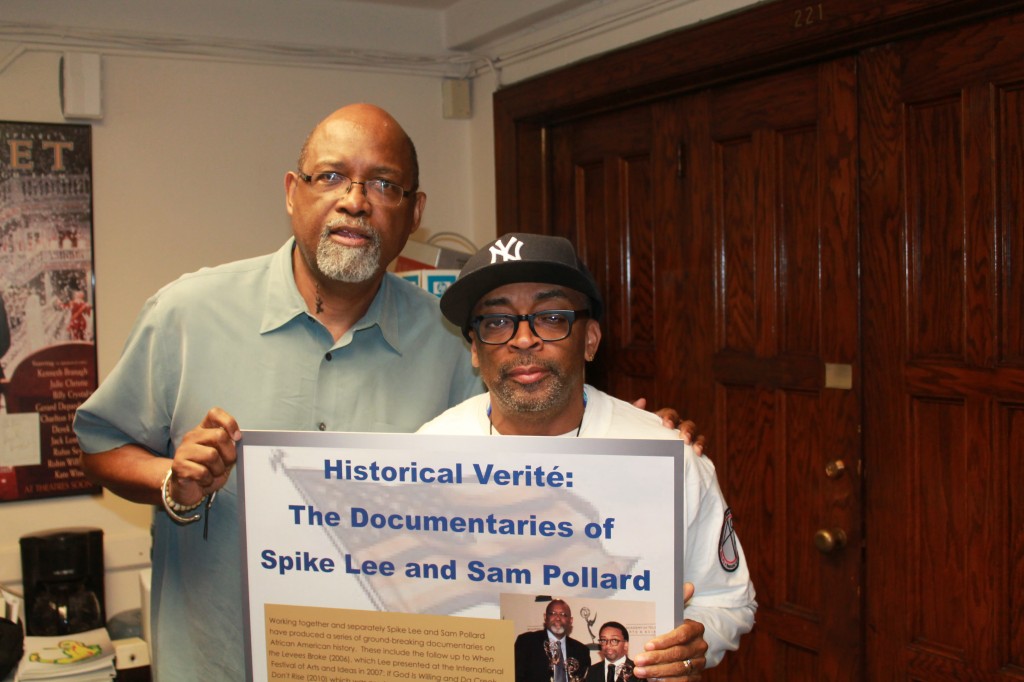

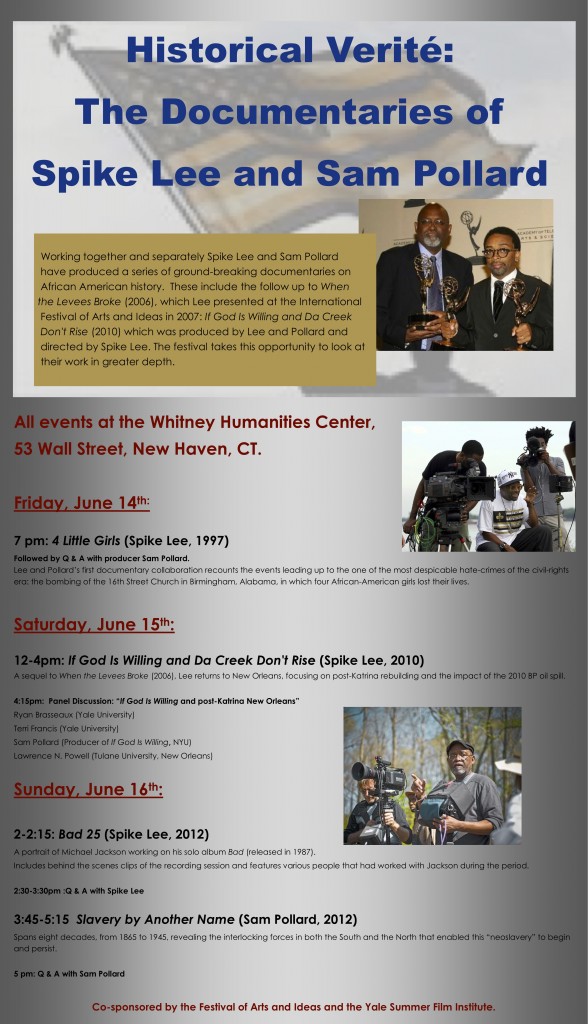

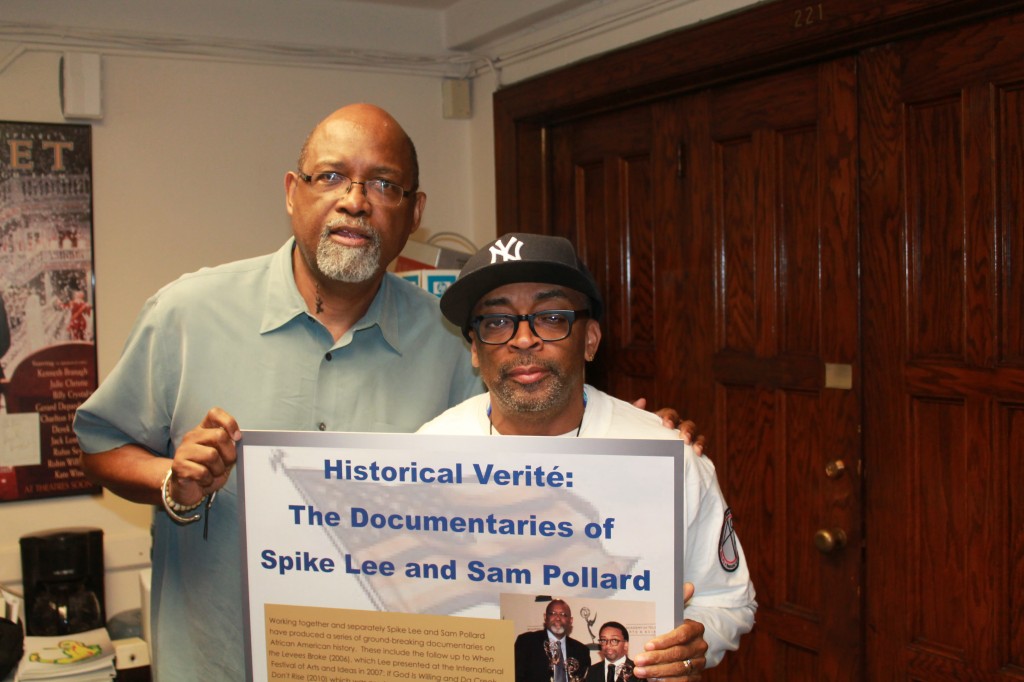

Historical Verité: The Documentaries of Spike Lee and Sam Pollard was a rewarding, intense––and sometimes tense–weekend of screenings and events. There were several compelling reasons for its programming. First we could show the sequel to When The Levees Broke (2006) which Spike Lee presented at the Festival in 2007–the first year of my collaboration with the International Festival of Arts and Ideas. Spike had filled the house–indeed as many people were turned away as got in. Attendance at Festival programs in subsequent years had been decent, but Spike connected with New Haven audiences in a special way. And yet, we obviously did not want to repeat ourselves. For quite a few years I have been interested in the collaboration between Spike and Sam Pollard. Sam had served as Spike’s editor on many of his fiction feature films since Mo’ Better Blues (1990), but they also had produced several documentaries together, on which Spike acted as director and Sam as editor. This duo is also interesting because, unlike Ismail Merchant and James Ivory (or the Maysles Brothers) they have often go their separate ways. That is, Sam is an accomplished director in his own right.

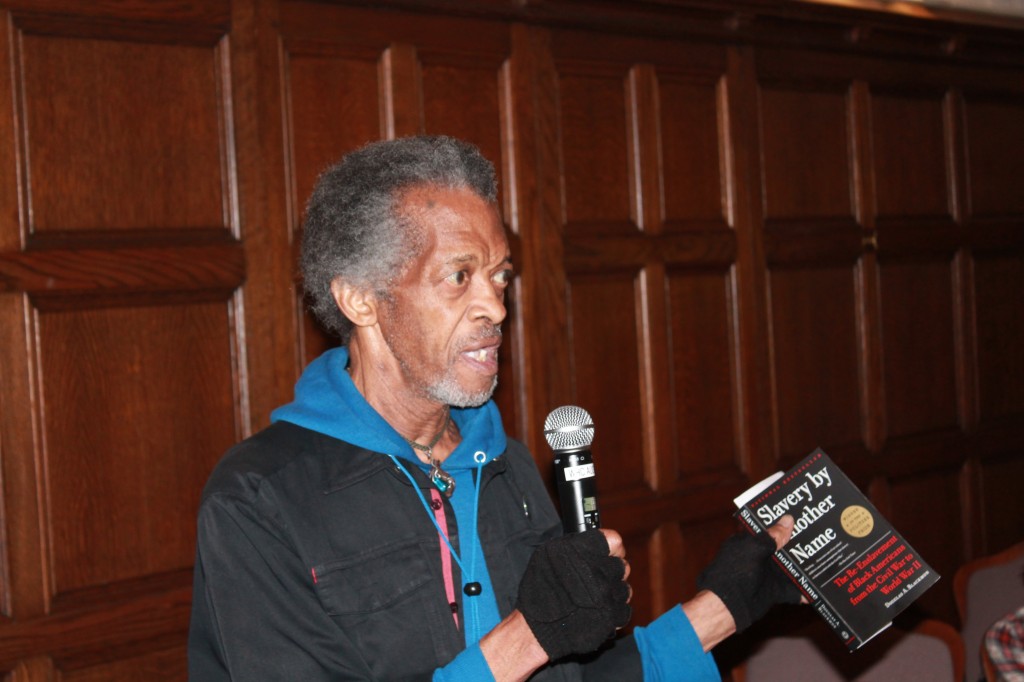

The program did several things. First Spike is commonly presented as a singular force––and his many critics use that distinctive voice, as a way to marginalize (and even demonize) him. This programming moved in the opposite direction by resituating him as part of a larger community of African American filmmakers working in documentary. Correspondingly, it provided a platform that put Sam on an equal footing with Spike when he is still seen too often as “Spike’s editor.” So we showed their first collaboration –4 Little Girls (1997)–– and their most recent–– If God is Willing and da Creek Don’t Rise (2010). And we also showed their most recent independently made documentaries: Lee’s Bad 25 (2012) and Pollard’s Slavery By Another Name (2012).

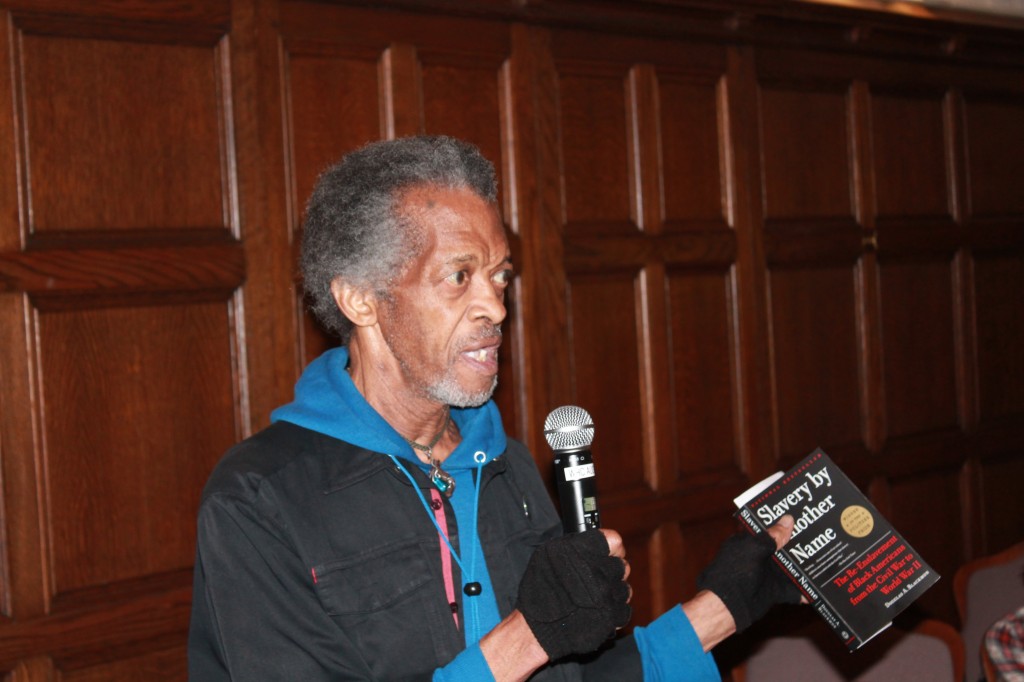

Although Sam introduced the opening film and was still present to take questions and answers after the final one, Spike came up specifically to show Bad 25––bringing the DVD of that film along with him. People were lining up outside the auditorium as early as 10 am on Saturday eager to see both Spike and his Michael Jackson documentary. Ultimately we had a standing room only crowd with a few late arrivals turned away. Meanwhile projectionist Tony Sudol was a nervous wreck because he had nothing to show until Spike arrived–-and we were a little nervous about that as well (it was Father’s Day after all). For all of the other films, Tony had played the DVDs a couple of times during the week to make sure everything would go smoothly. This time he was flying blind, and there were two moments when he must have had a near heart attack as the DVD of Bad 25 momentarily froze. But only momentarily.

Tony Sudol and Spike Lee

Of course, everything worked out in the end: given all the factors involved, it went pretty smoothly.

***

While Tony did his last minute checks, I took Spike to get a cup of coffee at the local coffee shop. There were two choices and he wanted to go for the one that was across the street.

His fans quickly popped out of several local storefronts and began to ask for photo ops. They hadn’t even known he was coming. At least one of them promptly dropped whatever she was doing and went to see the film. If I had taken Spike for a stroll through the New Haven green, we

probably could have filled the auditorium for some hypothetical second show.

***

After the screening of Bad 25, Spike discussed the film, how he came to work with Michael Jackson, and his conviction that Jackson was one of the greatest writers, singers, and performers with incredible discipline. In fact, my six-year old son John Carlos sat through the documentary (but not the Q & A–you can see him on the right edge of the stage in the photo below); When John Carlos got home, he discovered Michael Jackson videos on YouTube and began to practice a whole new set of dance moves.

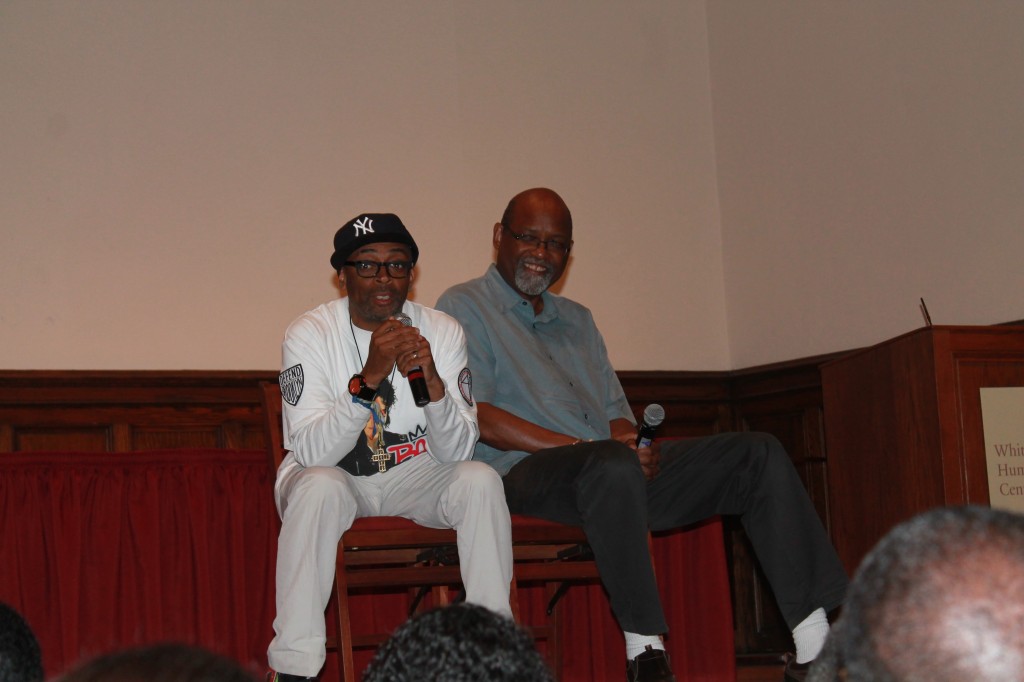

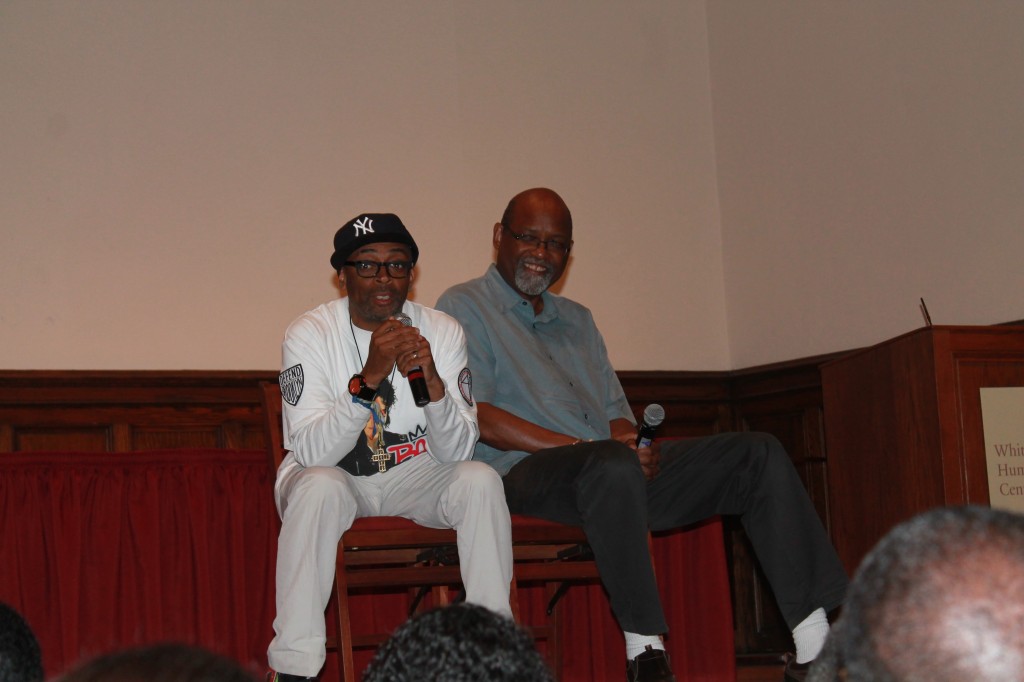

After a few remarks about the changing nature of New York City and the gentrification of Bedford-Stuyvesant by white urban professionals, Spike was joined by Sam on stage.

-

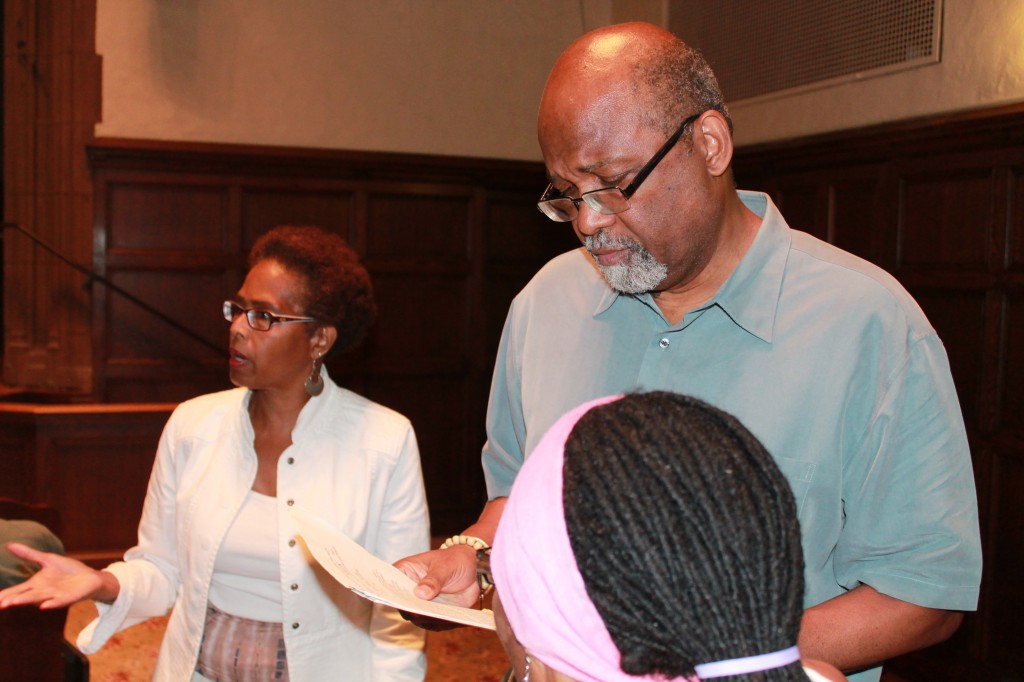

Spike Lee and Sam Pollard discuss their collaborative working relationship

Framing the documentaries under the rubric “Historical Verité” provided the weekend’s crucial intellectual insight. These films and the filmmakers share a common goal: to reveal aspects of American history and American culture that have been hidden, repressed. Bad 25 insists that viewers look at Jackson in a way that differs from the tabloid scandal sheets. Slavery By Another Name forces us to recognize that slavery did not end in the United States with the Emancipation Proclamation as we have been taught in school. It persisted in a variety of forms up until World War II. And in their sweeping epic, When the Levees Broke and If God is Willing and da Creek Don’t Rise give us a more complete and so more truthful understanding of the struggles which have faced New Orleans and its inhabitants since Katrina.

When writing these kinds of commentaries, journalists customarily provide “full disclosures” and here are mine. I met Sam Pollard in 1975 when we were both employed by Victor Kanefsky. We worked on separate projects in adjoining editing booths. I was cutting a medical film of some kind; who knows what Sam was doing. Kanefsky became an influential figure in Sam’s professional life, but I was just passing through. Nevertheless Sam and I hung out together, sometimes with my girlfriend Alexis Krasilovsky. And as usually happens in the film business, we lost touch–for at least two decades–until our paths once again began to intersect. He was teaching at NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts, where I had gotten my Ph.D. and had also done some teaching. But our first reunion may have been on the streets of New Haven when he came up to do some research at the Beinecke Library. I was also doing some writing on African American cinema, particularly the documentaries of William Greaves and Paul Robeson as well as the silent films of Oscar Micheaux. We  were pleased to discover that our professional lives were more in sync than we had any reason to expect. A couple of years ago he was a guest in my course on Digital Documentary and the Internet.

were pleased to discover that our professional lives were more in sync than we had any reason to expect. A couple of years ago he was a guest in my course on Digital Documentary and the Internet.

Spike and I also had had some intersections. My documentary Before the Nickelodeon: The Early Cinema of Edwin S. Porter (1982) was showing at the Berlin Film Festival the same year as Joe’s Bed-Stuy Barbershop (1982). And the film’s distributor, First Run Features was then run by Barry Brown, Spike’s other editor (he edited Bad 25). Spike worked there to make ends meet and we occasionally saw each other. Perhaps more importantly for me, my first published writing on black cinema was a on Do The Right Thing (1989) for Cineaste. When I submitted a review that characterized the picture as having the best use of film dialectics since  Eisenstein’s October, Cineaste decided to publish a round table discussion of the film with a reduced version of my review among an array of other commentaries. And, of course, whenever I went to see subsequent Spike Lee films, I’d usually see Sam Pollard’s name in the end credits. So bringing them together on the same stage in this way was personally satisfying. I hoped others would find it to be rewarding as well. In the end, this occasion provided me with a better sense of Sam’s career and one broader insight. Over the weekend, we discussed other black documentary filmmakers who shared the same “historical verité” project, including Saint Claire Bourne, William Greaves, and Bill Miles.

Eisenstein’s October, Cineaste decided to publish a round table discussion of the film with a reduced version of my review among an array of other commentaries. And, of course, whenever I went to see subsequent Spike Lee films, I’d usually see Sam Pollard’s name in the end credits. So bringing them together on the same stage in this way was personally satisfying. I hoped others would find it to be rewarding as well. In the end, this occasion provided me with a better sense of Sam’s career and one broader insight. Over the weekend, we discussed other black documentary filmmakers who shared the same “historical verité” project, including Saint Claire Bourne, William Greaves, and Bill Miles.

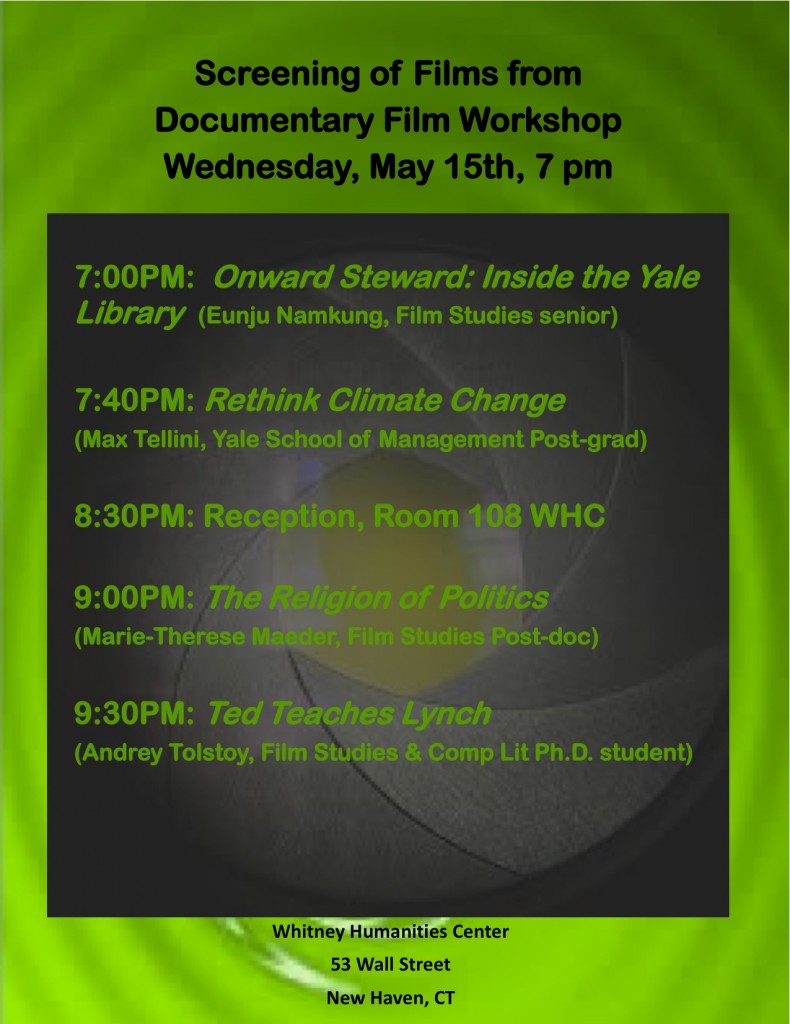

Our Weekend Festival of Documentaries has become an regular part of the International Festival of Arts and Idea and is made possible not only by the its Programming Director Cathy Edwards and Executive Director Mary Lou Aleskie but by Yale Summer Session and its Dean, William Whobrey. Of course if their support makes it possible in theory, many more people make it possible in practice, including Film Studies administrator Katherine Germano, projectionist Tony Sudol and the Festival staff which handles the front of the house while Nick Forster, Joshn Glick and Threese Serana gave added support.

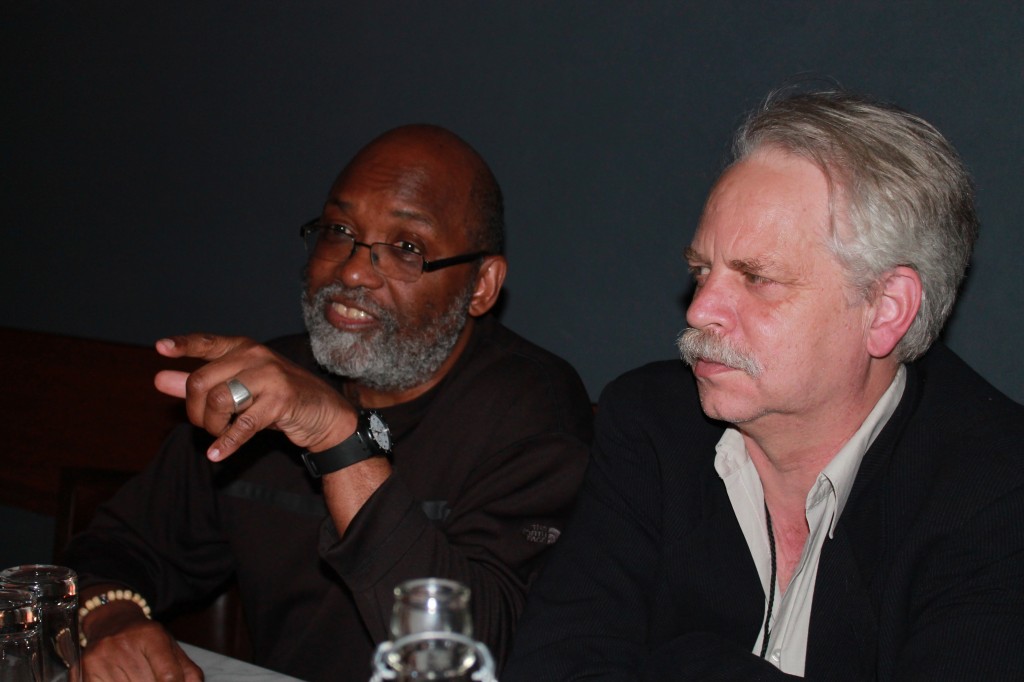

Dinner with Sam at Zafra

There is no cell phone service or Internet in Manlapay.

There is no cell phone service or Internet in Manlapay. Threese’s uncles, who owns a bakery and ended up doing some filming. A little like typical tourists, we were impressed with the

Threese’s uncles, who owns a bakery and ended up doing some filming. A little like typical tourists, we were impressed with the